PRUNING FOR BEAUTY, FUN, AND FLAVOR

Yew Love

Mundane as she may be, I love yew (not mispelled, but the common name for Taxus species, incidentally vocalized just like “you”). Hardy, green year ‘round, long-lived, and available in many shapes and sizes, what’s not to love? Perhaps that it’s so commonly planted, pruned in dot-dash designs to grace the foundations in front of so many homes.

Still, I love her. For one thing, Robin Hood’s bow was fashioned from a yew branch (English yew, T. baccata, in this case). Two other species — Pacific yew (T. brevifolia) and Canadian yew (T. canadensis) — are sources of taxol, and anti-cancer drug.

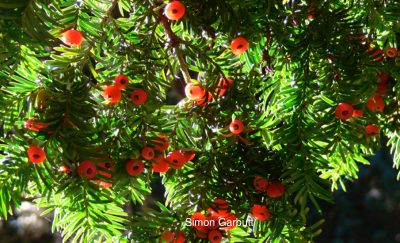

At a very young age, I became intimate with yew bushes surrounding our home’s front stoop, on which my brother and I would often play. Yew’s red berries, with an exposed dark seed in each of their centers, would give the effect of being stared at by so many eyes. Sometimes we’d squish out the red juice, carefully though, because we were repeatedly reminded that all parts of the plant are poisonous. (I’ve since learned that the red berries are not poisonous; but other parts of the plant, including the seed within each red berry are poisonous.)

If yew has, for me, one major fault, it’s that deer eat it like candy. Interesting, since grazing on yew can kill a cow or a horse.

Mostly, I love yew because she takes to any and all types of pruning. My father once had a very overgrown yew hedge threatening to envelope his terrace. I suggested cutting the whole hedge down to stumps. Following an anxious few weeks when I thought my suggestion perhaps overly bold, green sprouts began to appear along the stump. A few years later the hedge was dense with leaves, and within bounds.

Although usually pruned as a bush, yew can be pruned as a tree. A trunk, once exposed and developed, has a pretty, reddish color. Deer sometimes take care of this job, chomping off all the stems they can reach to create a high-headed plant with a clear trunk.

As an alternative to being pruned to dot-dash spheres and boxes, yew hedges can be pruned to fanciful shapes, including animals, or “cloud pruned” (niwaki, the Japanese method of pruning to cloud shapes). Many years ago, I followed the herd and planted some yews along the front foundation of my house, pruning them to one long dash. No dots.

Since then, I’ve converted that hedge to a giant caterpillar and, more recently, tired of the caterpillar and attempted to cloud prune it, not with great success so far. (It’s my shortcoming as a sculptor, not the plant’s fault.) The goal in this case is not the kind of cloud pruning with clouds as balls of greenery perched on the ends of stems. My goal is to blend the four plants together as one billowy, soft cloud.

Facing my kitchen window is another yew, a large one that was planted way before I got here. Its previous caretaker, and up to recently I, have maintained it as a large, rounded cone. Last year I decided to make that rounded cone more interesting, copying a topiary in Britain. The design is in its early stages, awaiting some new growth this year to fill in bare stems now showing in interior of the bush.

Not Too Late for Peaches

Moving on to more pragmatic pruning . . . peaches. No, it’s not too late. In fact, the ideal time to prune a peach tree is around bloom time, when healing is quick. This limits the chance of stem diseases, to which peaches are susceptible.

Peach tree, before pruning

Peach trees need to be pruned more severely than other fruit trees. As with other fruit trees, the goals are to avoid branch congestion so remaining branches can be bathed in light and air, to plan for future harvests, and to reduce the crop — yes, you read that right — so that more energy and better quality can be pumped into remaining fruits.

To begin, I approached my tree, loppers and pruning saw in hand, for some  major cuts aimed at keeping the tree open to light and air.

major cuts aimed at keeping the tree open to light and air.

Peaches bear each season’s fruits on stems that grew the previous season. So next, with pruning shears, possibly the lopper, in hand, I went over the tree and shortened some stems. This coaxes buds along those stems to grow into new stems on which to hang next year’s peaches.

And finally, I went over the tree with pruning shears, clipping off dead twigs as well as weak, downward growing stems. They can’t support large, juicy, sweet fruits.

Done. I stepped back and admired my work.

And, of course, for more about pruning, there’s my book, The Pruning Book.

And, of course, for more about pruning, there’s my book, The Pruning Book.