Too Much or Too Little?

The current deficit of rainfall reminds me of the importance of watering — whether by hand, with a sprinkler, or drip, drip, drip via drip irrigation — in greening up a thumb.

Not that watering is definitely called for here in the “humid northeast;” historically, cultivated plants have gotten by mostly on natural rainfall. Historically, vegetable gardens also weren’t planted as intensely as they are these days. In one of my three-foot wide beds, for example, brussels sprouts plants at eighteen inches apart are flanked on one side by a row of fully grown turnips and on the other side by radishes. Five rows of onions run up and down another bed.

The rule of thumb I use for watering is that plants need the equivalent of one inch depth of water once a week.

Finger in soil to test for moisture

This approximation doesn’t take into account the fact that my bed of sweet corn is thirstier than is my bed of onions, that my plants drew less water up from the soil during a recent calm, cloudy day than they will with today’s bright sunlight and breezes, and that warmer temperatures speed water loss. Still, an inch a week is a good approximation, one very workable around here where periodic rain allow some wiggle room in watering. Not so in parts of California and similar climates that remain reliably bone dry all summer.

A sprinkler, or a hand-held hose with a spray rose for small areas, and some randomly placed straight-sided cans to catch water are an easy way to tell how long to leave the spigot on to get that inch depth of water.  Usually, about an hour, once a week, is what it takes. (That’s a long time to stand still holding a hose.) Unless it rains. Then less might be needed.

Usually, about an hour, once a week, is what it takes. (That’s a long time to stand still holding a hose.) Unless it rains. Then less might be needed.

A rain gauge is an inexpensive way to know whether what seems like a soaking rain is really so. Or monitor soil moisture directly. Dig a hole, poke your finger into the soil, or, even better, purchase a “moisture meter” for less than $15; plunge the metal probe a few inches into the ground and read on the dial whether the ground down there is “dry,” “moist,” or “wet.” You want it moist.

Digital moisture probe.

Thirst Quenching a Drip at a Time

My vegetable plants get their thirst quenched with drip irrigation rather than a sprinkler. The idea of a drip system is to drip water into the soil at about the rate which plants are removing it. That doesn’t occur once a week, but every bright day, all day long.

That one inch per week rate translates to about three-quarters of a gallon per square foot.  My drip system is on a timer, and the time needed to apply this amount depends on the rate of flow from each emitter as well as the spacing of emitters.

My drip system is on a timer, and the time needed to apply this amount depends on the rate of flow from each emitter as well as the spacing of emitters.

After a lot of calculations and approximations (many years ago), I determined that dripping for one-half hour per day would be about right. But, as I wrote, plants drink all day long, not just once a day. My drip timer can turn on and off at three specified times per day, so the plants get their thirst quenched three times spaced out during daylight hours at ten minutes per session. My old timer offered six sessions per day; then, plants got six waterings of 5 minutes each.

Done. All I have to do is check every once in a while that all systems are go, which is one reason my drip lines run above ground. I can watch the dripping.

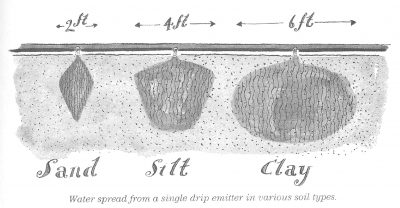

I do have to get out the watering can for the lettuce seedlings, the third planting of the season, that are soon to be set out, as well as for the recently planted row of carrot seeds and other recent seedings and transplants. Supplemental watering until roots of new plants stretch down into the region of the drip line’s wetting front, which spreads with the shape of an ice cream cone downward beneath each spot of dripping water.

(I’ll be leading a hands-on workshop on drip irrigation August 18th at the garden of Margaret Roach in Copake Falls. For more information, go to Margaret’s website, and type my name in the “search” box.)

Engineered Orifices

Note that I haven’t mentioned “soaker hoses.” Although the water oozes out from these porous hoses, they are not really “drip irrigation.” Sure, the water just oozes out slowly. But they’re inconsistent in output not only with water pressure and elevation, but also with time. And roots can grow inside buried soaker hoses, further muddying the water.

A real drip line has water emitters spaced six to twelve inches apart along their length, and those emitters aren’t mere holes punched in tubing. They are engineered orifices, designed to be relatively consistent in output with changes in incoming water pressure and changes in elevation along the line. They also are self-cleaning in case debris gets into the line.

And Now, A Word About Fireflies

Fun fact: Fireflies (which I knew as “lightning bugs” in my youth) are more than whimsy on a summer night; they’re also a gardener’s friend, feeding on, among other creatures, slugs.

The fittings for wending water through tubes around corners and up into pots are low pressure fittings; the pressure lowers water pressure to a mere 20 psi.

The fittings for wending water through tubes around corners and up into pots are low pressure fittings; the pressure lowers water pressure to a mere 20 psi. Part of the capillary mat dips into the reservoir of water, which gets sucked up into the mat and then sucked up into the potting soil through the drainage holes in each flat-bottomed plant pot.

Part of the capillary mat dips into the reservoir of water, which gets sucked up into the mat and then sucked up into the potting soil through the drainage holes in each flat-bottomed plant pot.

Usually, about an hour, once a week, is what it takes. (That’s a long time to stand still holding a hose.) Unless it rains. Then less might be needed.

Usually, about an hour, once a week, is what it takes. (That’s a long time to stand still holding a hose.) Unless it rains. Then less might be needed.

My drip system is on a timer, and the time needed to apply this amount depends on the rate of flow from each emitter as well as the spacing of emitters.

My drip system is on a timer, and the time needed to apply this amount depends on the rate of flow from each emitter as well as the spacing of emitters.