I’M AN INGRATE, AND RUTHLESS WITH FRUITLETS

/7 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening, Pests, Pruning/by Lee ReichGreat Asparagus Does Not Require A Green Thumb

Not to be an ingrate or a braggart, but the asparagus some friends recently brought over for our shared dinner didn’t compare with my home-grown asparagus. Not that the friends’ asparagus wasn’t good. Theirs came from a local farm, so I assume harvest was within the previous 24 hours.  But the stalks of my asparagus are snapped off the plants within 100 feet of the kitchen door, clocking in at anywhere from a few minutes to an hour of time before they’re eaten. It’s not my green thumb that makes my asparagus taste so good. It’s the fact that I can harvest it within 100 feet of my kitchen door.

But the stalks of my asparagus are snapped off the plants within 100 feet of the kitchen door, clocking in at anywhere from a few minutes to an hour of time before they’re eaten. It’s not my green thumb that makes my asparagus taste so good. It’s the fact that I can harvest it within 100 feet of my kitchen door.

But don’t take my word for it. Research has shown that asparagus spears begin to age as soon as they’re picked, the stalks toughening and sugars disappearing, and bitterness, sourness, and off-flavors beginning to develop. Yum.

Taste is just one of the many reasons to plant asparagus. Here’s more: Deer and other wildlife leave it alone so it doesn’t need to be corralled within a fence; the ferny foliage that needs to be let grow after harvest ends in early July makes a soft green backdrop for colorful flowers; a planting can pump out stalks from the end of April till the end of June (around here) for decades.

Asparagus’s two potential problems are relatively minor. The first is asparagus beetle, a beetle whose eggs, which look like black specks on the stalks, hatch into slug-like young that feed on the stalks. I keep this bugger in check by picking every single stalk — even spindly, inedible ones — every time the bed is harvested. The beetle, then, has nowhere to lay her eggs. (Not in my bed, least; she can seek out some wild asparagus here and there.) And then, at the end of the season, I cut down all the browned, ferny foliage and cart it over to the compost pile, in whose depths the adults, some of which overwinter in the old stalks, meet their demise.

No pesticides, organic or otherwise, have ever been sprayed on my asparagus, so natural predators also can do their share of making asparagus beetles a non-issue. Hand-picking beetles and larvae, which I’ve never had to resort to, is another way to keep the beetles in check. (My ducks may have a “hand” in that.)

Weeds are the other potential problem in an asparagus bed. One of the worst weeds in any bed is . . . asparagus! Each red berry dangling from the stems of a female asparagus plant houses a number of seeds that, once they hit ground level, can sprout to make new plants. The cure is to plant an all male variety of asparagus, such as Jersey Giant or Jersey Prince.

Unfortunately, a package of an all male variety can contain a few females. So, in addition to planting an all male variety, the cure for weeds is straightforward: Weed! I keep my bed regularly weeded during harvest season, then only occasionally weeded once fronds start to make the bed almost impenetrable.

Off With The Fruitlets (Some, At Least)

The slow but steadily increasing warmth this spring has been ideal for tree fruits (not so much the rainy weather). A bumper crop of fruitlets perch on branches of my apple and pear trees. It’s time to remove most of them.

These plants are genetically programmed to set more fruits than they could possibly have the energy to ripen. Spring presents many hazards to those blossoms, including killing freezes and insect pests. So, come June, when some of these threats have passed, fruit trees naturally shed excess developing fruitlets. But not enough.

The trees’ goals are to make seeds to make new trees. The seeds are enclosed within fruits that appeal to wildlife, who then help disperse the seeds. Those fruits might be good enough for wildlife, but not for you and me. For larger and more flavorful fruits, even more need to be removed than are shed by the “June drop.” Only 5 to 10 percent of apple blossoms need to set fruit for a full crop.

So I’m spending some time pinching or snipping off excess fruitlets, saving those that are largest and most free from blemishes, with a few inches between those that are left.

Fruit thinning is not only for flavor. A large crop one year bodes for a small crop the following; fruit thinning evens out any feast and famine cycle. The thinning also reduces some pest problems caused by fruits hanging too close to each other.

Pros And Cons Of Bad Weather (For Humans)

The recent spate of rainy weather has been accompanied by cool temperatures, which some plants enjoy and others wait out. Peas, cabbage, kale, and radishes are having a grand old time; sweet corn and beans wait out the cool weather.  The most dramatic response has been in the delphiniums, dames rockets, and giant alliums. With cool temperatures, their colorful displays go on and on.

The most dramatic response has been in the delphiniums, dames rockets, and giant alliums. With cool temperatures, their colorful displays go on and on.

Asparagus doesn’t mind hot or cool weather. The cool weather does slow down spear production, which made for insufficient harvest to share the day my friends came to dinner.

PERENNIAL VEGGIES AND A DEAD AVOCADO

/11 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening, Vegetables/by Lee Reich

King Henry Was, And Is, Good

The good king has gone to seed. Good King Henry, that is. A plant. But no matter about that going to seed. The leaves still taste good, steamed or boiled just like spinach.

The taste similarity with spinach isn’t surprising because both plants are in the same botanical family, the Chenopodiaceae, or, more recently, the Amaranthaceae. Spinach and Good King Henry didn’t change families; their family was just taken in by, and made into a subfamily of, the Amaranthaceae.

Whatever its name — and it’s also paraded under such common names as poor man’s asparagus and Lincolnshire spinach — Good King Henry is a vegetable that’s been eaten for hundreds of years, except hardly ever nowadays. While spinach, beet, and some of its other kin have been improved by breeding and selection over the years, Good King Henry was neglected.

But the Good King, besides having good flavor, has a few things going for it lacking in spinach. It’s a perennial plant, it’s edible all season long, and it has no pests problems worth mentioning. This Mediterranean native made its way to my garden over 20 years ago, from seed I purchased and sowed. I haven’t had to replant it since then.

Which brings me to one possible downside of Good King Henry: It keeps trying to spread beyond the far corner of the garden where I originally planted it. Every spring I yank out errant plants, and eat them.

One of my favorite things about Good King Henry is its species name, bonus-henricus, making its whole botanical name Chenopodium bonus-henricus.

Another Perennial Oldie

Another perennial vegetable that I’ve enjoyed this spring is seakale (Crambe maritima), a relative of cabbage, broccoli, and kale. This also is an old-timey vegetable, one whose popularity peaked in the 18th century; Thomas Jefferson was a fan.

The origin of the name may trace to the leaves (kale-like) being pickled to bring aboard ships (the “sea” part of the name) to prevent scurvy.

Seakale, though perennial, does not spread. I started my plants from seed a few years ago, which is tricky only because the seeds have a low germination percentage. I’ve seen a few seedlings pop up a foot or so from the mother plant, which I welcome as an easy way to multiply my holdings.

Seakale tastes very good either cooked or raw, something like a mild cabbage with a refreshing touch of bitterness. Either way, blanching is needed to make it tasty, and that entails nothing more than covering it for a couple weeks or so, more or less depending on the weather (more warmth, less time), to keep out light and make the shoots more mild and tender. I invert a clay flowerpot over the whole plant, with a stone or saucer over the drainage hole to keep light from wending its way in. Like asparagus, new leaves eventually need to be set free to bask in the sun to fuel the roots for the next year’s early shoots.

One more plus for seakale is that the plant is a beauty, so much so that it’s sometimes planted as an ornamental. The wavy, pale bluish green leaves have a silvery pallor reminiscent of the British seascape to which they are native. Later in the season, a seafoam of white blossoms rises from the whorl of leaves.

I Give Up

Now for an about face, from European plants enjoying cool weather and sometimes dry conditions, to a tropical American plant. Awhile back I wrote about my efforts to grow avocados here in New York’s Hudson Valley. Not on a large scale; just one or two plants from which I could harvest a few fruits of some special variety.

I grew two plants from seeds I saved from locally purchased avocado fruits, and grafted onto those seedlings the stems of two varieties a gardening buddy sent up from Florida. Ungrafted, the seedling plants would bear fruit of unknown quality, if they bore at all. Grafted plants would give me improved, named varieties that would bear quickly.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

I failed. Only one graft took, yet two varieties are needed for fruiting. As expected, the grafted stem on the successfully grafted plant flowered within a year of grafting. For days I tried to get the pollen from the male to pollinate the female parts of the flower — to no avail. And then, for some reason, the grafted stem started to darken and turn black, and died back.

I give up on trying to grow an indoor-outdoor avocado plant — for fruit — in a pot.

PERMACULTURAL GLITCHES

/6 Comments/in Design, Fruit, Gardening, Planning, Pruning/by Lee ReichImperfect Lawn

I’m no devotee of the perfect lawn, but I did recently suggest, for the bare palette of ground on which W wanted to plan for a variety of fruits, a patch of lawn. W protested that she hated mowing and wanted a “permaculture planting” that would take little care.

Visitors to my garden have occasionally complimented me on my lawn. The only care I give it is mowing with a mulching mower that lets clippings rain back down. By not cutting the lawn I avoid “mining” the soil for nutrients by repeated harvest of clippings. The clippings also enrich the ground with humus.

Pawpaw tree in my cousin’s lawn

Still, I’d rather grow trees, shrubs, vines, especially fruiting ones, and vegetables and flowers, than lawngrass. But I have plenty of ground devoted to these plants. And the easiest way to care for a plot of ground, short of sealing it in asphalt or just letting weeds grow (some of which would undoubtedly be edible or attractive) is by mowing. Visually, lawngrass also provide a calm backdrop for the scene out my back and front door. Plus, it’s nice to walk and play on.

A lawn need not be the environmental disaster inadvertently promoted by purveyors of fertilizers, and pesticides. As stated above, by letting clippings fall where they may, ground is not drained of its fertility, so fertilizer may not be needed. Especially if you let a little clover invade the lawn to add nitrogen, the most evanescent of plant nutrients.

That nitrogen highlights another approach to an easier lawn: Not striving for the uniform look of artificial turf. My lawn has its share of dandelions and clover and, later in the season, crabgrass, especially if the weather turns dry. I tolerate all this, with a refocussing of my aesthetic lens to celebrate a certain amount of diversity in the lawn.

Lawn care is even more environmentally sound these days with cordless electric lawnmowers not spewing noise, carbon dioxide, and other byproducts of gasoline consumption into the air. Periodic scything is a very pleasant way to get by with less mowing and sheep may be a way to get by with no mowing (but you do have to fence and do whatever else is necessary to care for the sheep).

Eco-mowers: Fiskars push, Stihl battery, and Scythe Supply Co. mowers

Fruits To (And Not To) Grow

Now for W’s permaculture fruit trees, shrubs, and vines — with some lawn, of course. (I think I convinced her.) For starters, I suggested steering clear of apples, peaches, plums, cherries, nectarines, and apricots. All are relatively high maintenance and, even with all that maintenance, still are iffy crops in this part of the world because of our extreme and variable climate and the plants’ susceptibilities to insects and diseases.

Nanking cherry hedge

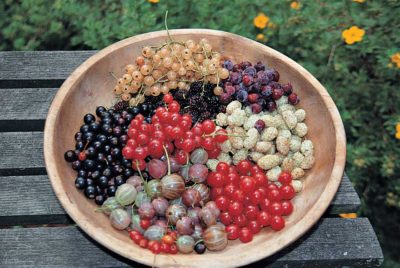

So what’s there left to grow??!! Berries, for one. Most berries don’t stand up well to commercial handling so are picked underripe even though they don’t ripen at all once harvested — all the more reason to grow berries in the backyard where the best tasting varieties can be planted and the harvest need not be shipped much further than arms’ length.

Redcurrant espalier

Raspberries, blackberries, blueberries, and strawberries are all easy to grow without much care beyond pruning, which is very important for keeping the plants disease free and convenient to harvest.

And no need to restrict the berry bowl to these most common berries. Also easy to grow are seaberries, elderberries, lingonberries, mulberries, and hardy kiwifruit (which are, botanically, berries). An added plus for these latter berries, as well as the aforementioned blueberries, is that the plants are also ornamental.

There is one common tree fruit that’s easy to grow: pears. And even easier than European pears, such as Bartlett, Anjou, and Bosc, are Asian pears, such as Chojuro, Yoinashi, Hosui, and scores of other varieties. Asian pears also bear more quickly and prolifically, and are a little more decorative than the also decorative European pears.

Asian pear, comfrey, and lawn

Avoiding Nightmares

The main problem that I’ve seen with many permaculture plantings is that they look great on paper as well as when first planted. Mouths water at the prospects of all those ornamental, fruiting plants cozied together, fruit on creeping plants beneath trees whose branches strain downward with their weight of fruit. And perhaps a nearby grape or kiwifruit plant insinuating its berried vines in among the trees’ branches.

I’ve seen such plans and such plantings. What a nightmare of management they are or will be, mostly because of the need for relentless, extensive, judicious pruning to keep some plants from overtaking the landscape and starving others for nutrients or light. The result is less fruit of lower quality and difficulty in finding the fruit and getting to it.

A little lawn is good to give the fruiting plants some elbow room and to make them easier to care for.

—————————————-

Don’t wait for dry weather to learn about an easy and better (for you and plants) way to water. On June 24, 1-4:30 pm, I’ll be holding DRIP IRRIGATION WORKSHOP at the garden of Margaret Roach in Copake Falls, NY. Learn how to design a system, and participate in a hands-on installation. For more information and registration, www.leereich.com/workshops.