Of Roses and Berries

/5 Comments/in Flowers, Fruit/by Lee ReichRoses Come and Go

I once grew a beautiful, red rose known as Dark Lady. For all her beauty, she was borderline cold-hardy here. Many stems would die back to the graft, and the rootstock, which was cold-hardy, would send up long sprouts. Problem is that rootstocks are good for just that, their roots; their flowers, if allowed to develop, are nothing special. After a few years of watching the weakened plant recover each season, I made cuttings from some of the stems. The cuttings rooted and the new plants, rather than being grafted, were then growing on their own roots. Even a cold winter wouldn’t kill the roots, living in soil where temperatures are moderated. If the stems died back to ground level, new sprouts would still sport those dark, red blossoms.

After a few years of watching the weakened plant recover each season, I made cuttings from some of the stems. The cuttings rooted and the new plants, rather than being grafted, were then growing on their own roots. Even a cold winter wouldn’t kill the roots, living in soil where temperatures are moderated. If the stems died back to ground level, new sprouts would still sport those dark, red blossoms.

I planted my new Dark Lady in a bed on the south side of my house. There, with the brick wall of the house adding a few extra degrees of warmth in winter and spring, Dark Lady might better survive winters coldest nights and get a jump on spring. What’s more, the roots had ample soil to explore rather than being restricted within the narrow, dry bed along my terrace where the mother plant had grown.

The new Dark Lady grew reasonably well in its new bed, but still not as well as I had hoped. Dark Lady is one of the many “English roses” bred by David Austin to have the blowsy look and fragrance of old-fashioned roses coupled with disease resistance and repeat blooming of contemporary roses.

Dark Lady eventually petered out. She’s been superseded by some newer creations from David Austin: L. D. Braithwaite and Golden Celebration are standouts as far a hardiness and beauty, and I expect the same of Dame Judi Dench and Lady of Shalott.

L D Braithwaite rose

Global warming has, no doubt, also been a help.

No Sharing of My Highbush Blueberries

Pity the poor birds. My fat, juicy blueberries have been ripening and now there’s a net between them and them. Putting up the net always brings the words of fruit breeder Dr. Elwyn Meader to mind. When I visited him back in the 1980s, the old New Englander, still active in his retirement and growing about an acre of blueberries, among other crops, recounted in his slow, New Hampshire accent, “It takes a patient man to net an acre of blueberries.” Covering my two plantings encompassing a total of about a thousand square feet always creates a little tension.

Putting up the net always brings the words of fruit breeder Dr. Elwyn Meader to mind. When I visited him back in the 1980s, the old New Englander, still active in his retirement and growing about an acre of blueberries, among other crops, recounted in his slow, New Hampshire accent, “It takes a patient man to net an acre of blueberries.” Covering my two plantings encompassing a total of about a thousand square feet always creates a little tension. I now feel like a captain setting sail on an old sailing vessel, with all the sails trim and masts set. Except rather than sails and masts, it’s a blueberry net that’s spread tightly over the permanent, 7-foot-high perimeter of locust posts and side walls of anti-bird, plastic mesh. That netting covers 16 bushes within a 25 foot by 25 foot area. Rebar through holes near the tops of the locust posts keeps that side wall mesh taught and 18” high chicken wire along the bottom keeps rabbits, which love to teethe on that plastic mesh, from doing so.

I now feel like a captain setting sail on an old sailing vessel, with all the sails trim and masts set. Except rather than sails and masts, it’s a blueberry net that’s spread tightly over the permanent, 7-foot-high perimeter of locust posts and side walls of anti-bird, plastic mesh. That netting covers 16 bushes within a 25 foot by 25 foot area. Rebar through holes near the tops of the locust posts keeps that side wall mesh taught and 18” high chicken wire along the bottom keeps rabbits, which love to teethe on that plastic mesh, from doing so. Don’t worry about the birds. They get their fill of berries elsewhere. I don’t net my lowbush blueberries, nor my mulberries or gumis. Birds don’t usually share the mulberries or gumis with me. This year, for some reason, they are sharing.

Don’t worry about the birds. They get their fill of berries elsewhere. I don’t net my lowbush blueberries, nor my mulberries or gumis. Birds don’t usually share the mulberries or gumis with me. This year, for some reason, they are sharing.

Juneberry, a Blueberry Look-alike

Birds also have free access to a blueberry look-alike, juneberries, the plants of which are sometimes called serviceberry, shadbush, and, in the case of one species, saskatoon. The bushes are common in the wild and, because of their pretty flowers, fall color, and neat form, also planted in landscapes.

Juneberries are small, blue, and dead-ringers for blueberries but have a taste all their own: Sweet with the richness of sweet cherries, along with a hint of almond. The birds seem to enjoy them as much as they do blueberries. Juneberries are related to apples and pears, not blueberries, and share some of their kin’s pest problems. Especially in my garden. They’re one fruit that didn’t grow well for me so, years ago, I finally dug the plants up.

Juneberries are related to apples and pears, not blueberries, and share some of their kin’s pest problems. Especially in my garden. They’re one fruit that didn’t grow well for me so, years ago, I finally dug the plants up.

Neither I nor birds need go far to find wild juneberries or bush or tree types planted for landscaping. They usually bear pretty well because of growing in microclimates more suitable than here on the farmden. In this low-lying valley, the air is too humid, cool, and conducive to disease.

With all the rain this spring, I’ve noticed that the crop on wild and cultivated juneberry plants has been hit hard by rust disease. I hear tell, though, that plants were bearing well at a nearby shopping mall: There, sunlight beating down on nearby concrete and, perhaps, less rust spores wafting about, create a microclimate conducive to good crops of berries.

——————————————

Any gardening questions? Email them to me at garden@leereich.com and I’ll try answering them directly or in this column. Come visit my garden at www.leereich.com/blog.

Uh Oh, Watch Out for This One!

/5 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichPast pests

Watch out for this one!

Over many years of gardening at the same location, I’ve seen pests come and go. And if they didn’t actually leave, they at least didn’t live up to the most feared expectations.A few years ago, for instance, late blight disease ravaged tomato plants up and down the east coast. The disease overwinters in the South and normally hitchhikes up north if temperatures are cool, humidity is high, and winds blow in just the right direction. That year it got a free ride here on plants sold in “big box” stores. I no longer consider late blight any more of a problem than it was before that high alert summer.

A few years ago, I was ready to say goodbye to my lily plants when I first heard of and then saw red lily beetles crawling and eating their way across my lilies’ leaves.  They’ve been making headway across the Northeast since arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1992. But my lilies still look fine and, yes, I do still see some of those beetles. Perhaps one of the natural predators released in Rhode Island years ago has joined the crowd here, minimizing damage.

They’ve been making headway across the Northeast since arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1992. But my lilies still look fine and, yes, I do still see some of those beetles. Perhaps one of the natural predators released in Rhode Island years ago has joined the crowd here, minimizing damage.

Japanese beetles were never a problem here until around 2006. I tried handpicking and trapping but their numbers — and damage — continued on the upswing.  Then, about 10 years later, and since then, they’ve showed up on schedule, which is now, but then disappeared for the rest of the season. Did they go off to greener pastures? Did they succumb to soil nematodes or fungi?

Then, about 10 years later, and since then, they’ve showed up on schedule, which is now, but then disappeared for the rest of the season. Did they go off to greener pastures? Did they succumb to soil nematodes or fungi?

And the spotted swing drosophila, which really went over the line by attacking my favorite fruit, blueberries.  Although chemical, mechanical, and biological controls are still under development, this pest has not put an end to my blueberry-eating days. Thanks to some bait and kill traps developed by Cornell’s Peter Jentsch, damage has been kept to a minimum.

Although chemical, mechanical, and biological controls are still under development, this pest has not put an end to my blueberry-eating days. Thanks to some bait and kill traps developed by Cornell’s Peter Jentsch, damage has been kept to a minimum.

The list goes on: marmorated stinkbug, leek moth, emerald ash borer, hemlock woolly adelgid . . .

Most Frightening of All!?

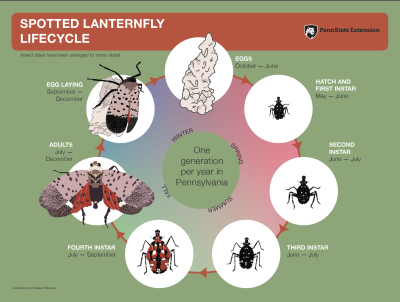

A new, most frightening pest is now lurking offstage. The spotted lanterfly (Lycorma deliculata, and heretofore to be abbreviated SLF) is an invasive leafhopper native to China, India, and Vietnam. It feeds on just about everything, including various hardwoods as well as grapes and fruit trees. To make matters worse, it also exudes a sticky honeydew which falls on any nearby surface (other leaves, lawn furniture, etc.) and, worse yet, becomes food for a fungus than turns that stickiness dark.

To make matters worse, it also exudes a sticky honeydew which falls on any nearby surface (other leaves, lawn furniture, etc.) and, worse yet, becomes food for a fungus than turns that stickiness dark.

This voracious pest can spread quickly; within 3 years of finding its a way into South Korea, it had spread throughout the country, about the size of Pennsylvania. And now SLF has arrived in Pennsylvania (well, actually, a few yers ago)!

In autumn, the lanternfly lays its eggs, which get a mud-like covering, on any hard surface, be it the bark of a tree, a rock, even a car bumper.  In spring, nymphs hatch and climb trees in search of soft, new growth. The one-inch long adults emerge around now; they’re very mobile, usually jumping but also capable of flying, which is when their spread wings display their bright red color. With wings folded, the insects are mostly gray wings with dark spots.

In spring, nymphs hatch and climb trees in search of soft, new growth. The one-inch long adults emerge around now; they’re very mobile, usually jumping but also capable of flying, which is when their spread wings display their bright red color. With wings folded, the insects are mostly gray wings with dark spots. A few natural predators, such as spiders and praying mantises, feast on SLF, but not enough. What to do? There are a few approaches.

A few natural predators, such as spiders and praying mantises, feast on SLF, but not enough. What to do? There are a few approaches.

A favorite host is tree-of-heaven, a weed tree that is not a favorite of most humans. Getting rid of these trees, then, is one way to limit spread of SLF. Problem is that a single female tree might produce 300,000 seeds per year; and the trees are hard to kill, resprouting and growing quickly from root sprouts.

Systemic pesticides injected into the trees would kill any insects feeding on them. Someone recounted to me of seeing a six-inch depth of dead SLF beneath infested, pesticide treated trees!

One thing you and I can do when leaving any area known to harbor SLF is to check what we’re taking with us, on the car bumper, for instance. Currently, certain southeastern counties of Pennsylvania are under quarantine, which means that movement of certain articles (such as brush, debris, or yard waste, landscaping or construction waste, logs, stumps, firewood, nursery stock, outdoor recreational vehicles, tractors, tile, and stone) is restricted out of these areas. Although established populations have not been reported elsewhere, individual insects have also been sited in nearby states.

Keep an eye out for eggs or adults on your property. If egg masses are found, scrape them off wherever they’re attached. Because authorities are trying to monitor spread of SLF, report any siting of eggs or adults, along with photographs and location (888-4BADFLY or spottedlanternfly@dec.ny.gov, for instance).

Insecticidal soap and Neem are two organic insecticides that are effective against SLF. Both are contact insecticides so will not kill insects that arrive after spraying.

By keeping an eye out for SLF and helping to limit its spread, we can keep this pest in check at least until some natural control can step in for the job.

Somethings Old, Somethings New, Nothing Blue

/4 Comments/in Gardening, Vegetables/by Lee ReichRare and/or Perennial

I usually draw a blank when someone asks me “So what’s new in your garden for this year?” Now, with the pressure off and nobody asking, I’m able to tell.

Of course, I often try new varieties of run of the mill vegetables and fruits. More interesting perhaps, would be something like the Noir de Pardailhan turnip.  This ancient variety, elongated and with a black skin, has been grown almost exclusively near the Pardailhan region of France. Why am I growing it? The flavor is allegedly sweeter than most turnips, reminiscent of hazelnut or chestnut.

This ancient variety, elongated and with a black skin, has been grown almost exclusively near the Pardailhan region of France. Why am I growing it? The flavor is allegedly sweeter than most turnips, reminiscent of hazelnut or chestnut.

I planted Noir de Pardailhan this spring but was unimpressed with the flavor. Those mountains near Pardailhan are said to provide the terroir needed to bring out the best in this variety. (Eye roll by me. Why? See last chapter in my book The Ever Curious Gardener for the skinny on terroir.) I’ll give Noir de Pardailhan another chance with a late summer planting.

Also interesting is Nebur Der sorghum. This seeds of this variety, from South Sudan, are for popping, for boiling, and for roasting. What sorghum has going for it is that it’s a tough plant, very drought resistant and cosmopolitan about its soil. With my previous attempt with sorghum, with a different variety, the seed didn’t have time to ripen. Nate Kleinman, of the Experimental Farm Network, where I got Nebur Der seed, believes this variety may ripen this far north.

Nate also suggested some perennial vegetables to try — that’s right, vegetables you plant just once and then harvest year after year. I planted Caucasian mountain spinach (Hablitzia tamnoides), a relative of true spinach, and, as predicted, growth is slow this, its first, year.  Next year I can expect a vine growing 6 to 9 feet high and which is both decorative and tolerates some shade. What’s not to like? (I’ll report back with the flavor.)

Next year I can expect a vine growing 6 to 9 feet high and which is both decorative and tolerates some shade. What’s not to like? (I’ll report back with the flavor.)

Andy’s Green Multiplier Onion (Allium cepa var. aggregatum), also from the Experimental Farm Network, will, I hope, fill that early spring gap here when some onion flavor can liven salads.  Later in the season, cluster of bulbs form, similar to shallots, although forming larger bulbs. They can overwinter and make new onion greens and bulbs the following years.

Later in the season, cluster of bulbs form, similar to shallots, although forming larger bulbs. They can overwinter and make new onion greens and bulbs the following years.

And finally, again from Nate, the New Zealand strain of perennial multiplying leek (Allium ampeloprasum). This seems to be a variable species, with some members yielding large bulbs know as elephant garlic. The flavor might vary from that of leek to that of garlic.

One more perennial plant (this one for the greenhouse so not really perennial here), is jicama (Pachyrhizus erosus), a climbing vine in the pea family. The flavor and texture of the large, turnip-shaped root is something like water chestnut. The flavor of the other parts of the plant are . . . not to be tried. All other parts are poisonous! The greenhouse is so hot in summer that I figured this is one of the few plants, besides figs and ginger, that would thrive there.

Probably not. I should have researched before planting: Jicama roots are poor quality unless the plant experiences a long period of warmth with short days. But when short days come around, my greenhouse is starting to fill with lettuce, mâche, spinach, and other fresh greenery for winter salads.

Could Be Frightening, But Not

At least one more newish crop made it into my garden this year, one that I hope is not perennial. The plant is sometimes called yellow nutsedge, sometimes chufa, and sometimes tiger nut or earth almond. When I lived in southern Delaware, “yellow nutsedge “would strike terror in the hearts of local farmers; it’s been billed as “one of the world’s worst weeds.”

But there are two botanical varieties of yellow nutsedge. That weedy one is Cyperus esculentus var. esculentus. The one that I am growing is C. esculentus var. sativus. The latter is not weedy; it rarely flowers or sets seed, and doesn’t live through the winter. Both varieties, being sedges, enjoy soils that are wet but also enjoy those that are well-drained.

The edible part of chufa are the dime-sized tubers, which are sweet and have flavor likened to almonds. I did grow the plant once and thought the tubers tasted more like coconut.  The problem was separating the small tubers from soil and small stones. I have a plan this time around — more about this at harvest time.

The problem was separating the small tubers from soil and small stones. I have a plan this time around — more about this at harvest time.

I’ll be in good company growing chufa. We humans munched on them in the Paleolithic period and they were good food to the ancient Egyptians. Hieroglyphic instructions detail the preparation of chufa for eating, as a sweet, for instance, ground and mixed with honey.

Even today, chufa is enjoyed in various parts of the world. The chufa harvest is anxiously awaited each year in Spain, when the dried tubers are washed and pulverized, then made into a sugar-sweetened “milk” know as “Horchata De Chufas.”