The End

/11 Comments/in Vegetables/by Lee ReichSnow Day

On December 2nd, my gardening season officially ended. It was brought to a screeching halt as a foot of heavy, white powder descended to democratically blanket my meadow, my vegetable beds, my terraces, and my deck.

I have to admit that it was welcome as I had spent the previous few weeks furiously getting ready for the end. Compost now covers most of the vegetable beds. Wood chips and neighbors’ raked leaves lie thickly beneath berry bushes and recently planted Korean pine (for nuts), chestnut, and pear trees.

Left in place, the one tunnel protecting a bed in the vegetable garden would have been collapsed by a heavy snow; I dismantled it. This tunnel consisted of metal hoops, 4 feet apart, each 5 feet long with either end pushed into the ground at each edge of the bed. The row of hoops was covered with vented, clear plastic and then, for added cold protection, a layer of “row cover” (a diaphanous fabric that lets air, water, and some light penetrate while affording a few additional degrees of cold protection).

I secured the clear plastic and the row cover layers by “planting” another metal hoop over them, right where the first hoops were”planted.” This setup makes it easy to slide the layers up and down, as needed, to reach in for harvest.

After dismantling the hoops and coverings, I picked over what remained. Cold had turned the few heads of lettuce left in the tunnel to mush. Surprisingly, a few small heads of pac choi (the varieties Joi Choi and Prize Choi) and large heads of napa type Chinese cabbage (the variety Blues) were in pretty much perfect condition.

My surprise came about because I had checked my minimum-maximum thermometer which registered the minimum temperature this fall as having dipped as low as 11° Fahrenheit. That’s very good protection from a thin layer of clear plastic topped by a layer of row cover — coupled with what are evidently quite cold-hardy varieties of Chinese cabbage.

Cloche History

Cold protection has come a long way since I started gardening. Over the years, cold protection devices, commercial and home-made, have undergone various incarnations in my gardens. Early on, with a bow to traditional cloches, I cut bottoms off gallon glass jugs for mini-greenhouses over individual or groups of very small plants.

(Cloche, pronounced klōsh, is the French word for “bell.” The original cloches were large bell-shaped jars that 19th-century French market gardeners placed over plants in spring and fall to act as portable miniature greenhouses. At one time, these glass jars covered acres of fields outside Paris that supplied out-of-season vegetables to the city’s households and restaurants.)

The classic glass bell jars are still available but have some significant limitations. Because they’re made from heavy glass and are small, the air trapped within can quickly get too hot on sunny days, cooking plants. And close attention needs to be paid to ventilation. A professional gardening friend, trained many years in France, tells of trudging out to cloche-covered fields on bright, frosty mornings to slide a block of wood under one side of each cloche to vent it during sunny days. In late afternoon he’d walk the field kicking out the blocks, setting each cloche flat on the ground to seal the warm air in for the night.

Although modern versions of these individual cloches are not as elegant as the traditional glass bell jars, some offer the same or a better degree of frost protection, are made of lightweight materials, are easier to vent, and are more convenient to store.

Modern variations on the cloche include: Clear umbrellas, which fold and unfold for easy storage, with spike handles that hold them in place; lightweight, durable, and inexpensive plastic versions of the traditional glass jar cloche; plastic milk jugs with the bottoms cut and vented by opening the lid; waxed-paper Hot Kaps. These vary in the degree of cold protection they offer as well as the size of the area they protect.

Tunnel type cloches protect whole rows or beds of plants. My original tunnel cloches were ersatz, British-made Chase cloches, which cleverly held glass panes into a ventable barn shape. Placed end to end, they created a tunnel, mini-greenhouse. I originally made my own from straightened coat hangar wire, then got hold of the real thing.

Chase cloches

Problem was, I discovered, that they work best in climates where temperatures are moderated, such as in northern Europe or near large bodies of water. (Anybody in those locations want some Chase cloche wires?)

So I graduated to the much more effective but much less attractive tunnel cloches, or “tunnels,” I described above.

SEEKING TRUTHS

/2 Comments/in Design, Gardening/by Lee Reich(The following is adapted from my most recent book, The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden, available from the usual outlets or, signed, from here.)

OBSERVE AND ASK

Charles Darwin did some of his best work lying on his belly in a grassy meadow. Not daydreaming, but closely observing the lives and work of earthworms, eventually leading to the publication of his final book, The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms. He calculated that these (to some humans) lowly creatures brought 18 tons of nutrient-rich castings to the surface per acre per year, in so doing tilling and aerating the soil while rendering the nutrients more accessible for plant use.

We gardeners can also take a more scientific perspective in our gardens without the need for digital readouts, flashing LEDs, spiraling coils of copper tubing, or other bells and whistles of modern science. What’s most needed is careful observation, an eye out for serendipity, and objectivity.

Observation invites questions. How many tons of castings would Darwin’s earthworms have brought to the surface of the ground in a different soil? Or from soil beneath a forest of trees rather than a grassy meadow?

And questions invite hypotheses, based on what was observed and what is known. Darwin’s prone observations, along with knowledge of soils, earthworms, plants, and climate, might invite a hypothesis such as “Earthworms would bring a greater amount of castings to the surface in a warmer climate.” Is this true? How can we find out?

MAKE A HYPOTHESIS

Gardens are variable and complex ecosystems, which makes growing plants both interesting and, if you want to know why a plant did what it did, frustrating. Many gardeners do something — spraying compost tea on tomatoes to reduce disease, for example — and attribute whatever happens in the ensuing season to the compost tea, ignoring the something else, or combination of things, that might also have made contributions to whatever happened.

Enter the scientific method, a way to test a hypothesis. You put together a hypothesis by drawing on what is known and what can be surmised. In spraying compost tea, your hypothesis, could be based perhaps on the idea that beneficial microbes in compost tea could could fight off pathogens, just as they do in the soil. (Many gardeners do, in fact, recommend compost tea for plant health. Do I? See https://leereich.com/2015/03/compost-tea-snake-oil-or-plant-elixir.html.)

Less disease on your sprayed plants would strengthen the case for further study. Why further study? Because the response of plants in a given season at a given location is not sufficient to make a general recommendation or make a theory.

The way to truly assess the benefit of the spray is to subject it to scientific scrutiny: Come up with a hypothesis, such as “Compost tea reduces tomato leaf diseases,” and then design an experiment to accurately test the validity of the hypothesis.

DESIGN AN EXPERIMENT

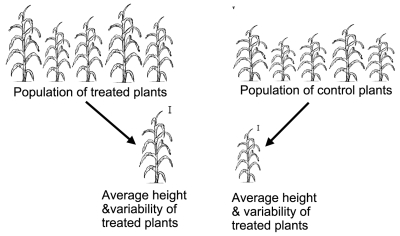

A well-designed experiment would need more than just one treated (compost tea sprayed) plant and one control (water sprayed) plant. Grow ten tomato plants of the same variety under the same conditions and some will grow a little more than the others, some a little less. With too few test plants, natural variation in growth from plant to plant might overwhelm any variation due to a treatment (spraying with the tea in this example). Given enough plants to even out the natural variations in, say, disease incidence, the effects of a treatment can be parsed out. Greater natural variations would require more plants for the test.

A garden experiment might have additional sources of variation. Perhaps one side of your garden is more windy, or the soil is slightly different, or basks plants in a bit more sunlight than the other side. Rather than have all the treated plants cozied together growing better or worse because of this added effect, even out these effects by randomizing the locations of treated and control plants.

Now we’ve got an experiment! All that’s needed is to spray designated plants with either the compost tea or the water, and then take measurements. Plug those measurements into a software program for statistical analysis and a computer will spew out a percent probability, based on variability within and between each group of plants, that the tea was responsible for less disease. A test with 90% or 95% probability is usually considered sufficient to link cause and effect. You can then answer “yea” or “nay” to the hypothesized question; you now have a theory, or not.

IS IT SIGNIFICANT?

A good test could involve a lot of plants and a lot of measurements, more than most of us gardeners are willing to endure. A danger exists, as Charles Dudley Warner so aptly put it in his 1870 book, My Summer in a Garden: “I have seen gardens which were all experiment, given over to every new thing, and which produced little or nothing to the owners, except the pleasure of expectation.” Then again, setting up something less than a full-blown experiment could be fun and, while not proving something to a 95% confidence level, still suggest a possible benefit.

Knowing what’s involved in testing a hypothesis also increases appreciation for all that can affect plants. Perhaps your tomato plants’ vibrant health wasn’t from your compost spray. Knowing something of the scientific method can help you assess, whether observed in your own garden or a friend’s garden, or reported in a scientific journal, the benefit of the spray.

So go out to your garden and look more deeply into Nature, perhaps, like Darwin, lying on your belly. Understanding some of the science at play in the garden takes it to the next level. And you’ll find that the real world, neatly woven together, is imbued with its own poetry, with science being one window into that poetry.

Me mulching, even as a beginning gardener

FRUITS OF ISRAEL

/4 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening/by Lee ReichOlives Galore

Now I feel foolish buying olives. I recently returned from visiting Israel where there were olive trees everywhere. Irrigated plots of greenery thrived in the broad expanses of the otherwise grays and browns of the desert. Trees popped up here and there in backyards and front yards of homes in streets lined with apartment buildings as well as along cobblestone streets in rural areas. Trees were even prominent in city parks, either as self-sown wildings in less tended areas or as formal plantings.

And oodles of ripe or ripening olives were clinging to branches or littering the ground. Need some hand lotion? Just pluck a ripe olive, squeeze it gently, and spread out the fresh oil that drips onto your hand.

Want some olives for eating? Not so fast. Fresh-picked ripe or green olives are extremely bitter (due to oleuropein). That bitterness is removed with brine, multiple changes of water or lye solution followed by fermentation. My favorite olives are “naturally, sun-cured,” which, I imagine, means left hanging on the tree a long, long time. The dried, ripe olives I found still-clinging to branches tasted awful!

I was tempted to harvest some olives to bring home. A few other people had similar ideas, as evidenced by one woman on a ladder in a park in Jerusalem. Of course, these people were only miles or less from home; I was 5,000 plus miles from home. I let the olives be.

I actually grow olives here in the Hudson Valley, in a large container that spends summers outdoors basking in sunlight and winters in my cold basement near a large window. I should say that I grow an olive tree, rather than olives. My maximum harvest has been a half-dozen olives — which I did let hang for a long, long time, at which point they tasted delicious.

Olive fruits are borne on one-year-old shoots. This year, before moving my tree to the basement, I pruned more severely than usual. That should stimulate more one-year-old shoots this spring, to, I hope, yield more fruit.

——————————————

Another of my favorite Mediterranean fruits also growing in abundance in as many guises as olive in Israel was pomegranate. Unfortunately, I just missed the harvest of this fruit. All that remained on wild plants were a few red arils still clinging to darkened portions of skins. Fruits must have been ripe somewhere because ripe fruits and fresh squeezed juice were available in markets and and street carts everywhere.

I, of course, also grow pomegranate, similarly to olive except that, being deciduous, this plant does not need light in winter. It spends those months in a dark, walk-in cooler.

Sad to admit, my yields of pomegranate fruits have been even less than my yields of olive. As in zip, zilch, zero. The plants flower every spring and with a small brush I’ve transferred pollen from the anthers of male blossoms to the stigmas of female blossoms. (Plants each have separate male and female blossoms.) Bases of female blossoms begin to swell hopefully. Then they drop.

Every year I threaten my plant with a walk to the compost pile — to no avail.

——————————————

The third plant of the triumvirate of my favorite Mediterranean fruits is, of course, figs, which I saw in abundance in Israel mostly in wild settings. The plants lacked fruit, except for a few with small, green figlets that will either drop or ripen next spring. Fig is rather unique in its fruiting habit, able to bear fruit on one-year-old wood as well as on new, growing shoots, and the latter crop just keeps forming and ripening as long as growing conditions are to its liking.

One old tree growing in a courtyard in charming town of Sfad was hosting an old friend — or, rather, enemy — of mine, fig scale insects. I’ve battled it one my greenhouse figs.

Figs were available in the markets but I was reluctant to even try them knowing that figs must be dead ripe to taste good. At that, stage they can hardly be transported more than arm’s length from hand to mouth.

Figs are one Mediterranean fruit that I grow with great success, both in my greenhouse (minimum winter temperature 37°F) and, wintering in my walk-in cooler and summering outdoors, in pots like my pomegranate. Figs are generally easy to grow because of their unique bearing habit, their lack of need for pollination, and their general tolerance for abuse.

My last day I broke down and, against my better judgement, bought some figs. Mine are better.