I MAKE TREES

/6 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichHere are 3 Easy, Fun Grafts I Made Yesterday

Finally, the weather cooperated and I got around to doing some grafting. I could have done it a couple of weeks ago, as I had planned, but I’m blaming cooler weather for the delay. Not that I couldn’t have done it back then, but things chug along more quickly in warmer weather, so I waited.

Apple tree on very dwarfing rootstock

I’m going to describe 3 easy grafts I did yesterday. Which one I chose to do depended on the size of the rootstock on which I was grafting. The scions, which are the varieties I’m grafting on the rootstocks, are all one-year-old stems 6 to 12 inches long and more or less pencil-thick (remember what pencils are?). They have been stored, wrapped to prevent drying out, in the refrigerator so that they are more asleep than the awakening rootstocks.

The principles that make any graft work are all the same. Close kinship of stock and scion. Close proximity of the cambium — the layer just beneath the bark — of the stock and of the scion. All open wounds sealed against moisture loss. And immobilization of rootstock and scion until graft succeeds. My book, The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden, goes into more detail about the why and the how of grafting.

A Tree Make Over

For starters, I turned to the bark graft, good for grafting on rootstocks a couple or more inches across. This first graft was on a Tyson pear tree whose flavor wasn’t up to snuff, so that graft began with doing a Henry the Eighth, lopping off the tree’s head to graft height, which was a couple feet from ground level.

The bark graft comes with an good insurance policy. That’s because onto each rootstock, depending on its diameter, I can stick 3, 4, 5, or even more scions. Only one scion needs to grow, but the more that are grafted, the greater the chance of at least one growing.

I prepared a scion with a bevel cut 2 inches long, at its base, not quite all the way across from one side to the other. On the opposite side of the cut, I nicked off a short bevel.

Then, into the freshly cut stub on the rootstock, I made two vertical slits through the bark, each about 2 inches long and as far apart as the width of the base of the scion.

Carefully peeling back the flap of bark welcomed in the long, cut surface of the scion, putting the cambial layers of rootstock and scion in close contact. This was repeated with the other scions, all around the stub. With the peeled back flaps of bark from the rootstock pushed back up against each inserted scion, one or two staples from a staple gun or a tight wrapping with stretchy electrician’s tape sufficed to hold everything in place.

Finally, I sealed all cut surfaces against moisture loss, for which there are a number of home-made and commercial products. My favorite is a commercial product called Tree-Kote, a black goo that works really well and absorbs sunlight.

Another Tree Make Over, For Smaller Trunks

For smaller rootstocks, say 3/4 inch up to a couple of inches across, there’s the cleft graft. This also comes with an insurance policy, though not as good as that of the bark graft because it only gets two scions per graft. Still, it’s easy so chances for success are high.

At the base of each of the two scions, I made two bevel cuts less than halfway through, each two inches long and not exactly on opposite sides. Viewed head on and from below, the uncut portion was slightly wedge-shaped.

Turning to the rootstock, an older rootstock (OH x F 87), I lopped it off squarely, with a saw, then created a split a couple of inches deep in the middle of the cut surface by hammering a heavy, sharp knife right down into it. After removing the knife, a screwdriver pushed down into the split separated it enough to insert the two prepared scions at each edge of the cleft with their cambiums aligned with the cambium of the rootstock.

Pulling out the screwdriver caused the springiness of the rootstock to close the cleft and hold the scions securely in place. As with the bark graft, all cut surfaces got smeared with Tree-Kote.

And Some Baby Tree Grafts

The whip graft is my graft of choice when rootstock and scion are about the same thickness, pencil-thick. Rootstocks for whip grafts were again OH x F87 pears, this time one-year-old rootstocks, pencil-thick.

I cut at the bottom of the scion with a smooth, sloping cut an inch to an inch and a half long, and made a similar cut at the top of the rootstock.

Holding the sloping cuts against each other and aligning just one edge of each if their diameters didn’t exactly match, I bound rootstock and scion together with a rubber grafting strip. (I’ve also used thick rubber bands, sliced open.)

Wrapping whip graft

As with any graft, cut surfaces must be sealed against moisture loss. Parafilm® helps holds the graft together and seals in moisture. Once my whip graft scions are growing strongly, I’ll cut a vertical slit into the binding to prevent it from choking the plant.

Bark graft, season 3, note flowering

There you have it: 3 easy grafts to make new trees or make over an older tree. Now the excitement begins, watching and waiting for new growth. Sometimes, with that large root system fueling growth, a bark graft scion will grow 2 or 3 feet its first season!

PRUNING FOR BEAUTY, FUN, AND FLAVOR

/16 Comments/in Fruit, Pruning/by Lee ReichYew Love

Mundane as she may be, I love yew (not mispelled, but the common name for Taxus species, incidentally vocalized just like “you”). Hardy, green year ‘round, long-lived, and available in many shapes and sizes, what’s not to love? Perhaps that it’s so commonly planted, pruned in dot-dash designs to grace the foundations in front of so many homes.

Still, I love her. For one thing, Robin Hood’s bow was fashioned from a yew branch (English yew, T. baccata, in this case). Two other species — Pacific yew (T. brevifolia) and Canadian yew (T. canadensis) — are sources of taxol, and anti-cancer drug.

At a very young age, I became intimate with yew bushes surrounding our home’s front stoop, on which my brother and I would often play. Yew’s red berries, with an exposed dark seed in each of their centers, would give the effect of being stared at by so many eyes. Sometimes we’d squish out the red juice, carefully though, because we were repeatedly reminded that all parts of the plant are poisonous. (I’ve since learned that the red berries are not poisonous; but other parts of the plant, including the seed within each red berry are poisonous.)

If yew has, for me, one major fault, it’s that deer eat it like candy. Interesting, since grazing on yew can kill a cow or a horse.

Mostly, I love yew because she takes to any and all types of pruning. My father once had a very overgrown yew hedge threatening to envelope his terrace. I suggested cutting the whole hedge down to stumps. Following an anxious few weeks when I thought my suggestion perhaps overly bold, green sprouts began to appear along the stump. A few years later the hedge was dense with leaves, and within bounds.

Although usually pruned as a bush, yew can be pruned as a tree. A trunk, once exposed and developed, has a pretty, reddish color. Deer sometimes take care of this job, chomping off all the stems they can reach to create a high-headed plant with a clear trunk.

As an alternative to being pruned to dot-dash spheres and boxes, yew hedges can be pruned to fanciful shapes, including animals, or “cloud pruned” (niwaki, the Japanese method of pruning to cloud shapes). Many years ago, I followed the herd and planted some yews along the front foundation of my house, pruning them to one long dash. No dots.

Since then, I’ve converted that hedge to a giant caterpillar and, more recently, tired of the caterpillar and attempted to cloud prune it, not with great success so far. (It’s my shortcoming as a sculptor, not the plant’s fault.) The goal in this case is not the kind of cloud pruning with clouds as balls of greenery perched on the ends of stems. My goal is to blend the four plants together as one billowy, soft cloud.

Facing my kitchen window is another yew, a large one that was planted way before I got here. Its previous caretaker, and up to recently I, have maintained it as a large, rounded cone. Last year I decided to make that rounded cone more interesting, copying a topiary in Britain. The design is in its early stages, awaiting some new growth this year to fill in bare stems now showing in interior of the bush.

Not Too Late for Peaches

Moving on to more pragmatic pruning . . . peaches. No, it’s not too late. In fact, the ideal time to prune a peach tree is around bloom time, when healing is quick. This limits the chance of stem diseases, to which peaches are susceptible.

Peach tree, before pruning

Peach trees need to be pruned more severely than other fruit trees. As with other fruit trees, the goals are to avoid branch congestion so remaining branches can be bathed in light and air, to plan for future harvests, and to reduce the crop — yes, you read that right — so that more energy and better quality can be pumped into remaining fruits.

To begin, I approached my tree, loppers and pruning saw in hand, for some  major cuts aimed at keeping the tree open to light and air.

major cuts aimed at keeping the tree open to light and air.

Peaches bear each season’s fruits on stems that grew the previous season. So next, with pruning shears, possibly the lopper, in hand, I went over the tree and shortened some stems. This coaxes buds along those stems to grow into new stems on which to hang next year’s peaches.

And finally, I went over the tree with pruning shears, clipping off dead twigs as well as weak, downward growing stems. They can’t support large, juicy, sweet fruits.

Done. I stepped back and admired my work.

And, of course, for more about pruning, there’s my book, The Pruning Book.

And, of course, for more about pruning, there’s my book, The Pruning Book.

Spring: A Manic Time in the Garden

/23 Comments/in Flowers, Fruit, Planning/by Lee ReichThe Season’s Ups and Downs

To me, spring can be a manic time of year. On the one hand, no tree is more beautiful or festive than a peach tree loaded with pink blossoms. I’d say almost the same for apples, pears, and plums, their branches laden with clusters of white blossoms.

And it’s such a hopeful season. If all goes well, those blossoms will morph, in coming months, into such delicacies as Hudson’s Golden Gem and Pitmaston Pineapple apples, and Magness, Seckel, and Concorde pears. My peach tree was grown from seed, so has no name. With all this beauty and anticipation, I can periodically forget the pandemic that’s raging beyond my little world here.

But even as my eyes feast on the scene and I forget about the pandemic, I can’t forget about the weather’s ups and downs. Specifically, the temperature: Frosty weather has the potential to turn blossoms to mush and ruin the chances for fruit. Especially on my farmden, here in the Wallkill River valley. As in other low-lying locations, on clear, cold nights, a temperature inversion occurs, with heat radiated to the clear sky making ground level temperatures low. Cold air is denser than warmer air, so all the cold air flows down slopes to collect in valleys.

There’s not much to do to avert that frost damage. A blanket thrown over a tree would help but my trees are too large and too many. Branches could be sprayed with water; water, in transitioning to ice, releases its heat of fusion as long as it’s continuously applied. A helicopter or a “wind machine” could dilute colder air at ground level with warmer air from higher up. These methods might be used commercially but, to quote the sage of Newburgh (that’s another story), “That’s not gonna happen” here.

Therapy, a Plan

Rather than worrying myself into the manic phase of spring, I’m going to assess the damage and live with it. For starters, I need to know the temperature.

I have been using is a nifty little device called Sensorpush, a 1-inch square cube, perhaps a half-inch thick, that I have mounted outside and that continually transmits the temperature to my cell phone. Great. Even better, temperature (as well as humidity) is recorded, and can be displayed graphically or downloaded to my computer. So I didn’t have to be awake to find out the mercury hit 32.5°F at 12:16 AM on the night of April 17th and stayed there until it began rising around 7 AM.

Great. Even better, temperature (as well as humidity) is recorded, and can be displayed graphically or downloaded to my computer. So I didn’t have to be awake to find out the mercury hit 32.5°F at 12:16 AM on the night of April 17th and stayed there until it began rising around 7 AM.

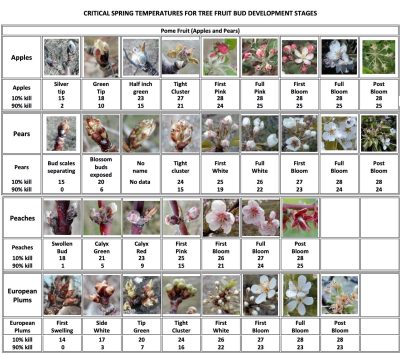

Fortunately, researchers have compiled temperatures at which damage to blossoms occurs. Specifically, damage enough to wipe 10% of the crop, and damage enough to wipe out 90% of the crop. And more specifically, applying those numbers to various kinds of fruits, which vary in their blossom’s cold tolerances. And even more specifically to the various stages of blossoming for each kind of fruit. Generally, less cold is required to kill a blossom the closer it is to bloom time.

Here is a chart compiled and photographed by Mark Longstroth of Michigan State University:

So now I can take this information, couple it with data recorded by Sensorpush, and foretell my sensory future, pomologically speaking. Below freezing temperatures since trees awakened have been 24° on April 17th, 27° on April 19th, and 26° on April 21st. Of course, it ain’t over till it’s over, and the average date of the last frost here is about mid-May.

Peach bloom

Plum blossoms

My plum trees were in full bloom on April 13th, at which time the blossoms are susceptible to 10% kill at 28° and 90% kill at 23°. That makes only 10% loss. The peach tree was also in bloom on that date, and is very similar in it’s blossom’s cold tolerance, so only 10% loss there also, so far.

Asian pears were showing “first white” and “full white” on April 19th, when the low hit 27°. That temperature would cause them no damage. The same would be true, going forward, for subsequent temperatures above 27°. The Europeans should be fine because today, April 21st, they are in tight cluster, and cold hardy to 24°.

Asian pear full white

European pear tight cluster

Apples also are fine, also in tight cluster so, according to the chart, undamaged by temperatures above 27°.

Apple blossom tight cluster

And a Sprinkle of the Unknown

All this seems very science-y comforting, and it is. As with most garden science, though, things are more complicated, to some extent, than can be easily predicted. For one thing, some variation in cold hardiness undoubtedly exists from one variety to the next. In the case of my trees, I have an American hybrid and some European hybrid plums; they might more generally differ in blossom hardiness. And what about the length of time at a given temperature, and the effect of humidity?

Overall, the chart has calmed me down. Not to mention that a certain amount of fruit loss would be a good thing. A tree has just so much energy, and too big a crop makes for less flavor and size. Only 5% of blossoms of an apple tree need to set fruit for a full crop.

Now, I can move on to worry about insect and diseases that might hone in on my fruit.