NOW, WITH COVID-19, ANOTHER REASON TO GARDEN

/19 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichNot Necessarily Anti-Social

I’m feeling very lucky these days, lucky to be happy to stay home. An important way to deal with the current COVID-19 pandemic, both from a personal and a societal standpoint, is not to be out and about.

(If you are infected, you may not show any symptoms for awhile, or symptoms may be very mild. During that time, though, you could infect others. It’s estimated that, at present, every infected person infects 3 others before they get well or die. Those 3 other each infect 3 more, and so on; ten transmissions has almost 60,000 people infected.

Social distancing brings that number of 3 new infections from each infected person down to a number of cases our health care system would be able to handle. So stay at home, if possible, maintain a six foot distance from other humans, be aware of contaminated objects and surfaces, and wash hands frequently.)

For all the downsides of the internet, a big plus now is the ability it gives us to interact socially without spreading disease.

Home is Nice, Gardening

What’s so great about staying home? In my case, I have my garden, of course. Spring, as always, is a busy time in the garden. Busy, such as: attending to my compost. The last compost pile of late fall and winter is an accumulation of end-of-season debris from garden cleanup, bedding from the duck house, and kitchen scraps. Not much happens in it with the slow additions and winter cold. I decided to dig into the pile to see how it was doing. Not good!

Busy, such as: attending to my compost. The last compost pile of late fall and winter is an accumulation of end-of-season debris from garden cleanup, bedding from the duck house, and kitchen scraps. Not much happens in it with the slow additions and winter cold. I decided to dig into the pile to see how it was doing. Not good!

The innards were smelly and sodden, which could have been avoided if I had regularly thrown some straw, autumn leaves, or any other dry, old plant matter into it periodically. Oh well.

Given enough time, even that smelly, cold, sodden pile would turn to compost. I prefer to speed things up, getting the pile hot and quickly killing many weed seeds.

Aeration and some dry material could remedy the situation. I left home and got a load of horse manure mixed with dryish sawdust bedding from a nearby stable. (No human contact was needed to get the manure). Then I began turning the pile, layering in the manure and some old hay that I had cut and raked last fall. The way I tell how its doing is by taking its temperature with a long-stemmed compost thermometer. Three days after the turning, the pile is warming, 90° and rising.

Seed Starting, When?

Busy, such as: starting seedlings indoors for later planting outdoors. The ideal is to have seedlings the right size when it’s time for that outdoor planting, so they can make a smooth transition from container to ground hardly knowing they’ve been moved. Each vegetable has its own timetable for how fast it grows to transplant size and then when it can be planted outdoors.

For instance, here on the farmden, the historical average date of the last killing frost is May 21st. Cabbage seedlings need about 6 weeks of growth before they’re large enough to transplant. Since they tolerate some cold, they can be planted out here on May 1st. Six weeks before May 1st is March 15th, which is when I sowed those seeds.

Let me also use tomato as an example because that’s one that many gardeners plant too early or too late. Tomato seeds need about 7 weeks of growth before they’re ready to plant out. Freezing temperatures are not good for them, so I plant them out around the end of May. The end of May minus 7 weeks is around April 1st, which is when I’ll be sowing tomato seeds.

Sowing and planting dates are not set in stone. Temperature, potting mix, and container size all influence how fast seedlings grow. And there’s wiggle room because sowing or planting out tomatoes a week earlier or later doesn’t change the date of the first harvest that much because plants grow slowly early in the season.

One thing to avoid is being pushed around too much by the weather. Don’t let a 3 day warm spell in March convince you to sow tomatoes then, or a 3 day warm spell in early May to plant out tomatoes earlier. In the first case, the plant, being too large at transplant time, will have a harder transition to open ground; you’ll harvest earlier tomatoes, but less over the whole season. In the latter case, a subsequent cold spell might kill the plants (unless you cover them for protection).

I detail out recommended sowing and planting dates for vegetables according to locale in my book Weedless Gardening. At the very least, write down what you do in your garden this year and tweak it closer and closer each season.

Planting, What?

Busy, such as: planting out new trees, shrubs, and vines. After so many years here at the farmden, you’d think that I would have planted every tree, shrub, or vine I could have wanted. Tain’t so.

I’m very specific about what varieties I want to plant so I usually order bare root plants, which are available in greater variety than potted plants. Ideal size for a tree is about 4 feet high because their roots can establish in their new home quickly. Of course, a potted plant, if that variety is available locally, would establish even more quickly.

In the pipeline this year are Egremont Russet and Rubinette apples, Dr. Goode grape, Mohler persimmon, and a number of low bush blueberries and lingonberries.

I remember a sunny day years ago, right after hurricane Irene. The back part of my property, where my vegetable gardens are, was high and dry, a glorious early fall day. But turning 180 degrees, looking to the front, the Wallkill River and associated flood debris was flowing past my doorstep. These days, my thoughts are often on COVID-19. Again, the garden — or a hike in the woods and other home enjoyments — provide needed respite from a bad situation.

INTO THE WOODS

/19 Comments/in Gardening, Planning/by Lee ReichForest Garden Skeptic

“Forest gardening” or “agroforestry” has increasing appeal, and I can see why. You have a forest in which you plant a number of fruit and nut trees and bushes, and perennial vegetables, and then, with little further effort, harvest your bounty year after year. No annual raising of vegetable seedlings. Little weeding, No pests. Harmony with nature. (No need for an estate-size forest; Robert Hart, one of the fathers of forest gardening, forest gardened about 0.1 acre or 5000 square feet.)

Is this a forest garden?

Do I sound a bit skeptical? Yes, a bit. Except in tropical climates, forest gardening would provide only a nibble here and there, not a significant contribution to the diet in terms of vitamins and bulk. A major limitation in temperate climates is that most fruit and nut trees require abundant sunlight to remain healthy; the same goes for most vegetables.

The palette of perennial vegetables in temperate climates is very limited, especially if you narrow the field down to those tolerating shade. I’m also not so sure that weeding would be minimal; very invasive Japanese stilt grass has been spreading a verdant carpet on many a forest floor whether or not dappled by sunlight.

The case could be made — has been made — that some of the dietary vegetable component could be grown on trees. Robert Hart wrote of salads using linden tree leaves instead of annuals such as lettuce and arugula. I’ll admit that I’ve never chewed on a linden leaf. (I’ll give it a try as soon as I come upon one that has leafed out.) My guess is that its taste and texture would leave much to desire.

And how about squirrels? I grow nuts, and part of my controlling them involves maintaining meadow conditions around the trees. This exposes them to predators, including me and my dogs, without their having tree tops to retreat to and travel within. Unprotected, I’ve had nut plants stripped clean by squirrels.

The book Edible Forest Gardens by Dave Jacke offers a very thorough exploration of forest gardening.

But Did I Plant a Forest Garden?

I’ve actually planted a forest garden! Well, perhaps not a forest garden. Over 20 years ago, I did plant a mini-forest. My forest, only about 300 square feet, was originally planted for fun (I like to plant trees), for aesthetics, and for some nutrition. So far I’ve reaped immense visual rewards for my effort.

Here’s what I planted: Bordering a swale that is rushing with water during spring melt and periods of heavy rain went four river birch (Betula nigra) trees. They evidently enjoy the location for they’re now each multiple trunked with attractively brown, peeling bark and towering to about 60 feet in height.

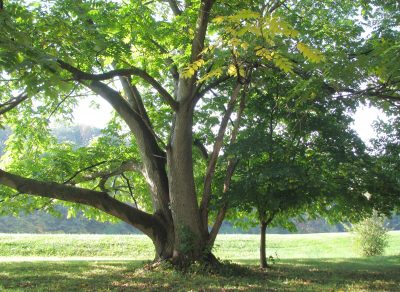

River birch

I also planted 3 sugar maple trees to provide sap for maple syrup for the future. The future is now (except I no longer use enough maple syrup to justify tapping them.) I also planted a white oak (Quercus alba), whose sturdy limbs, I figured, would slowly spread wide with grandeur in about 150 years, after the maples and birches were perhaps long gone. Unfortunately, the white oak died, probably due to winter cold; its provenance was a warmer winter climate. My mistake.

I also planted a white oak (Quercus alba), whose sturdy limbs, I figured, would slowly spread wide with grandeur in about 150 years, after the maples and birches were perhaps long gone. Unfortunately, the white oak died, probably due to winter cold; its provenance was a warmer winter climate. My mistake.

Since that initial planting, I’ve also planted a named variety of buartnut (Juglans x bixbyi), which is a hybrid of Japanese heartnut and our native butternut.

Buartnut (not mine, yet)

I hadn’t realized it, but that tree has grown very fast and now spreads its limbs wide in much that habit as a white oak. The other two trees that I planted are named varieties of shellback hickory (Carya laciniosa). These trees are slow growing but eventually will offer good tasting nuts. They’re quite pretty, even now, with their fat buds.

A Vegetable Also

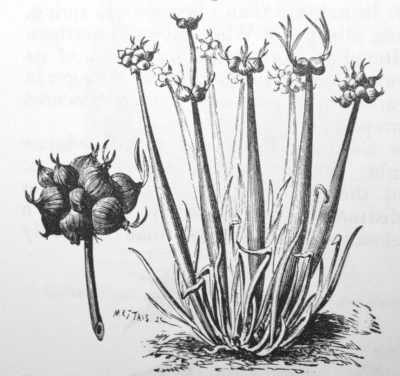

What about vegetables in my mini-forest? They were not part of my original plan. It turns out that ramps, a delicious onion relative, a native, which I’ve been growing for a few years beneath some pawpaw trees, are spring ephemerals. Spring ephemerals are perennial plants that emerge quickly in spring to soak up sunlight before its blocked by leaves on trees, then grow and reproduce before the tops die back to the ground.

Ramps (Allium tricoccum) are perfect forest vegetable, so I wanted to make the ground beneath my mini forest more forest-y before moving the ramps from beneath the pawpaws. Nothing fancy. All I did was to haul in enough leaves to blanket the ground in the planting area a few inches deep. That leafy mulch will suppress competition from weeds and add organic matter to the soil.

Collecting ramps for transplanting

In just a few years, the ramps will be sufficiently established to provide good eating, perhaps along with some buartnuts and hickory nuts, all from my forest(?) garden.

Drip Opportunity

I’m looking for a site within 20-30 minutes of New Paltz, NY in which to hold a drip irrigation workshop. What I need is a vegetable garden in beds (not necessarily raised beds) for which I would design a drip system. Workshop attendees I would install the system after learning about drip irrigation. Host pays fo materials. Contact me if interested.

ALL ABOUT ONIONS

/10 Comments/in Vegetables/by Lee ReichAn Ode

Onions, how do I plant thee? Let me count the ways. I plant thee just once for years of harvests if thou are the perennial potato or Egyptian onion. If thou are the pungent, but long-keeping, American-type onion, I sow thy seeds in the garden in the spring. And if I were to choose like most gardeners, I would plant thee in spring as those small bulbs called onion “sets.” (Apologies to E.B. Browning)

New Old Ways with Onions

Early March brings us to yet another way of growing onions: sowing the seeds indoors in midwinter. This was the “New Onion Culture” of a hundred and fifty years ago, and, according to a writer of the day, “by it the American grower is enabled to produce bulbs in every way the equal of those large sweet onions which are imported from Spain and other foreign countries.” This is the way to grow the so-called European-type onions.

Walking onions

What’s wrong with growing perennial onions, American-type onions, and onion sets? Neither perennial nor American-type onions have the sweet flavor of the famous Vidalia onion, a European type. And onions for sets are generally limited only to the two varieties marketed, Stuttgart and Ebenezer, whose important quality is that they make good sets. A few seeds companies sell sets of a better variety, Forum. In addition to variety, quality of sets is important: too large and they become useless as they send up seedstalks.

The New Onion Culture is a way to grow the large, sweet, mild European onions, such as Sweet Spanish.

The “Method” is as follows: About 10 weeks before the last hard freeze, fill a seed flat with potting soil and use a plant marker to make furrows 1/2-inch deep and one inch apart. Drop about seven seeds per inch into the furrows and then cover the seeds with soil. Fresh seed, less than a year old is best. Water the flat, then keep it moist and warm and covered with of pane of glass. The onions should sprout in a week or two.

Once the onions sprout, remove the plastic or glass and give the seedlings plenty of light. Put the flat either within a few inches of fluorescent lights, on a very sunny windowsill, or in a greenhouse. Each time the seedlings grow to six inches height, clip them back to four inches. The trimmings, incidentally, are very tasty. This indoor stage of plant growing can be bypassed by purchasing onion transplants (not sets), which are sold mail-order in bundles of twenty-five.

Get ready for transplanting a few weeks before the predicted last freeze date. Choose a garden spot where the soil is weed-free, well-drained, and bathed in sunlight. Onions demand high fertility; my plants go into a bed that was dressed with an inch depth of compost last fall. Give the onion seedlings their final haircut, tease their roots apart, then set them in a furrow, or individual holes dibbled with a 3/4-inch dowel. Plant seedlings two to four inches apart, two inches if you want small bulbs, four inches if you want big bulbs.

This may sound like a lot of trouble to grow onions. But for me, midwinter onion sowing inaugurates the new gardening season. The onion is an apt inaugural candidate; it responds to “high culture” starting with careful sowing in fertile soil and moving on to good weed control, timely watering, and, after harvest, correct curing after harvest.

Besides providing this midwinter ritual, onions raised according to the New Onion Culture do have superb flavor.

(The above was adapted from my book A Northeast Gardener’s Year.)

And Still Newer Ways

And now for the “Newer Onion Culture”: American-type onions have the advantage of being better for long-term storage, and newer varieties also have very good flavor. My current favorites are Copra, Patterson, and New York Early. They also are “long day” onions, setting bulbs when the sun shines for 15 to 16 hours daily. “Short day” varieties, which are adapted to the South, would bulb up too soon around here, producing puny bulbs.

There’s more to the “Newer Onion Culture.” A couple of years ago, a local farmer, Jay, of Four Winds Farm, told me he gets good results by just planting seeds in furrows right out in the field.

And even more. Instead of planting 7 seeds per inch indoors in furrows in early March, sow them in flats of plastic “cells” with 4 seeds per cell (each cell is about an inch square).  When transplanting out in the garden, plant each cell with its seedlings intact, spacing them further apart than you would with individual transplants so their roots get adequate water and nutrition. As vegetable growing maven Eliot Coleman wrote in Four-Season Harvest, “the onions growing together push each other aside gently.”

When transplanting out in the garden, plant each cell with its seedlings intact, spacing them further apart than you would with individual transplants so their roots get adequate water and nutrition. As vegetable growing maven Eliot Coleman wrote in Four-Season Harvest, “the onions growing together push each other aside gently.”

Back to my original query: “Onions, how do I plant thee.” Many ways. I’ll do four out of the six ways this season.