MY BICOASTAL PLANT

/6 Comments/in Pruning/by Lee ReichA Tree Takes a Plane Ride

I managed to pack lightly for a journey, many years ago, to the West Coast, toting along only an extra pair of pants, a couple of shirts, and a few other essentials. But on the return trip, how could I resist carrying back such bits of California as orange-flavored olive oil and chestnut-fig preserves? The most obvious bit of California that I brought back was a potted bay laurel plant (Lauris nobilis), its single stem poking out of my small backpack and brushing fragrant leaves against the faces of my fellow travelers.

Bay, with its subtropical pals, rosemary and citrus

Not only did the bay laurel bring a bit of California to my home, but also traditions dating back thousands of years from its native home along the Mediterranean coast. Ancient Romans crowned victors with wreaths of laurel and bestowed berried branches upon doctors passing their final examinations. (The word “baccalaureate” comes from bacca laureus, Latin for “laurel berry”.) Bay laurel was sacred to Apollo, so was planted near temples.

Although bay laurel can grow fifty feet tall, my plan was to develop this plant into a small tree with a single, upright trunk capped by a pompom of leaves. The Mediterranean climate is characterized by hot, dry summers, and cool, moist winters. Since the plant is hardy only to about fifteen degrees Fahrenheit, I had to grow it in a pot. The plant is allegedly a rich feeder, but my plants grows fine in my homemade potting mix which contains a healthy portion of compost and — for some extra oomph — some soybean meal.

The potted tree decorates the house in winter, the terrace in summer, and provides fresh bay leaves for soups and other dishes year-round.

A Winter Home

It is in winter that my plant realizes just how far it is from its Mediterranean home. Winters in its home lands are typically cool and moist. Winters inside a northern home are typically warm and dry. Since cool rooms are moister than warm rooms in winter, the cooler the room the better, preferably below fifty degrees. My bay laurel has wintered well either in sunny window in a cool room or near a bright window in my basement, where temperatures are very cool. The warmer the temperatures, the more light bay laurel needs.

The other challenge to my bay tree has been scale insects. They sit along leaves and stems under their protective shell as they suck sap from the plant.  Actually, it’s more of a challenge to me because the plant tolerates scale reasonably well. Once moved outdoors in spring, the plant soon recovers from the attack and its resident scale population, either from the changed environment or from predators, subsides.

Actually, it’s more of a challenge to me because the plant tolerates scale reasonably well. Once moved outdoors in spring, the plant soon recovers from the attack and its resident scale population, either from the changed environment or from predators, subsides.

The problem for me is that the insects exude a sticky honeydew that drips onto furniture and the floor. A sooty black fungus then feeds on the honeydew.

This summer I’ve taken a more active role in thwarting scale by spraying the plant weekly with horticultural oil, which is nontoxic to humans and soon evaporates.

Lollipops

Bay laurel can be trained to any number of shapes such as a pyramid, cone, or globe, with these shapes beginning at ground level or capping a long or short piece of trunk.

Right from the get go, I chose to grow my tree as a “standard.” “Standard” has many meanings both in and out of horticulture, so let’s first get straight which kind of “standard” we are dealing with: Here, I mean a naturally bushy, small plant trained to have a clear, upright stem capped by a mop of leaves. A miniature tree.  In the world of gardening, people are divided over how they feel about “standards.” Some gardeners love them, others will have nothing to do with them.

In the world of gardening, people are divided over how they feel about “standards.” Some gardeners love them, others will have nothing to do with them.

(A “standard” apple tree is one grafted to a rootstock that does not confer any dwarfing.)

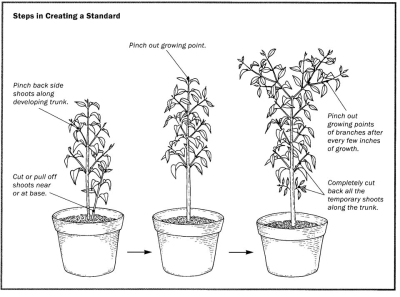

For training my lollipop-shaped bay tree, I allowed only a single stem to grow straight upward, and then pinched off any side shoots that developed. When the trunk reached three feet in height, I pinched out the tip to cause branches to form high on the stem. I kept this up, pinching branches and then their branches, to cause further branching, thus forming a dense head. (I devote a whole chapter to standards in my book The Pruning Book.)

Training a standard (rosemary, in this case)

Or, in an illustration (from The Pruning Book):

Ongoing care of the tree entails pruning and pinching to keep the mop head to size, and root pruning and repotting the plant every couple of years or so. The time to do any trimming to keep a plant in shape is mostly just as soon as the new shoots mature and stop growing in early summer.

A few years ago, I decided that my tree was too tall and unwieldy; I wanted a shorter standard. Easy: I just lopped the whole plant to the ground and started again. With an established root system fueling new growth, I was able to develop the new lollipop quickly.

All this pinching and pruning yields fresh bay leaves, which find their way into the kitchen. The fresh leaf has a strong flavor, and one cookbook suggests (and I now confirm this) using one leaf for a dish to serve four people. The aroma of the fresh leaf is more than just strong; it actually has a different quality than that of the dried leaf. The fresh aroma is almost oily, to me somewhat reminiscent of olive oil — how California-ish!

A BACTERIA TO THE RESCUE

/6 Comments/in Pests/by Lee ReichA Cabbageworm is a Cabbageworm is a . . . Not!

A few weeks ago, one or more of the few species of “cabbageworms” began munching the leaves of my cabbage and Brussels sprouts plants. They ignored kale leaves, thankfully, because it’s my favorite of the three.

A laissez fair approach would have left the cabbages and Brussels sprouts mere skeletons, so I had to take some sort of action.

For the record, “cabbageworms” are actually not worms, but a few species of caterpillars all classified — and this is important — in the order Lepidoptera. Here’s the lineup: A cabbage looper arches its back when moving, and is light green with a pale white stripe along each of its sides and two thin white stripes down its back.

Cabbage looper

A diamondback moth larvae is 5/16 inch long, yellowish-green, and spindle shaped with a forked tail.

Diamondback moth larva

A cabbageworm (yes, one kind of cabbageworm is named “cabbageworm”) is one-and-a-quarter inches long, velvety green, and has a narrow, light yellow stripe down the middle of its back.

Cabbageworm & cross-striped cabbageworm

A cross-striped cabbageworm is 3/4 inch long and bluish-gray in color with many black stripes running cross-wise on its back, below which a black and yellow stripe runs along the length of its body.

Natural Control

I put an end to whichever “worms” were the culprits, and was able to do so without resorting to any chemical spray, by spraying the plants with Bt. Bt is the commonly used abbreviation for Bacillus thuringiensis, a bacterium that causes disease in certain insects. After ingesting Bt, a cabbageworm becomes sick, stops eating, and dies. Since the Bt I sprayed is toxic only to lepidopterous insects, it doesn’t pose any danger to other creatures, such as birds, cats, dogs, humans, and even other insects.

The insecticidal properties of Bt have been known since early in the twentieth century, when the bacterium was discovered as a silkworm pest by Japanese researchers. (Silkworms are also Lepidoptera.) The originally discovered strain of this bacteria is toxic only to caterpillars, which are larvae of butterflies and moths, and was first used purposefully to control the European corn borer in Europe in the 1930s. Interest in Bt waned in the late 1940s, when nerve gases used during World War II led to the development of new types of chemical pesticides. In the 1960s, agricultural scientists finally began to take a second look at Bt.

Many strains of Bt have been isolated. The ones for cabbageworms and other Lepidoptera are Bt aizawai and Bt kurstaki.  The strain Bt var. israelensis is toxic to larvae of black flies and mosquitoes. Another strain, Bt var. san diego, is toxic to Colorado potato beetle larvae.

The strain Bt var. israelensis is toxic to larvae of black flies and mosquitoes. Another strain, Bt var. san diego, is toxic to Colorado potato beetle larvae.

All these strains of Bt are available commercially. The bacteria are packaged in a dormant condition either as a dry powder, a liquid suspension, or, in the case of Bt var. israelensis, a slow release ring that is floated on water to kill mosquito larvae. Bt goes under a number of brand names which don’t give a hint of the pesticide’s ingredients, so read the label to make sure of what you are buying. The product I use goes under the trade name Thuricide.

Bt is a living organism, so I store it in such a way as to prolong its viability. (Here on the farmden, Bt resides in the back of the refrigerator, which is generally a strong no-no for pesticides. (But Bt is nontoxic, and there are no children in the house.) Kept cool and dry, the bacteria will remain viable in its container for two or three years. Bt works quickly enough so I can check for discolored, blackened, or shriveled larvae the next day to see if the spray is still viable.

But . . .

Is there some trade-off that must be made when using this apparently benign pesticide? Yes, insect pests can develop resistance to Bt, just as they do to chemical pesticides. Resistance is most likely from continuous, repetitive use of any single pesticide, or different ones with the same mode of action.

This problem, with Bt, has been exacerbated since almost 500 million acres of crops, mostly field corn and cotton, have been genetically engineered with insecticidal Bt genes. It’s equivalent to the field being constantly sprayed with Bt. Some resistance has been found.

In my garden, I apply Bt at the recommended rate, only to afflicted plants, and only when a pest problem gets sufficiently out of hand to warrant treatment.

There’s another good reason for careful use of at least the original strain of Bt. Since this strain is toxic to caterpillars, indiscriminate use could substantially decrease the caterpillar population and, hence, the numbers of moths and butterflies. My distaste for the celeryworm, which has a voracious appetite for carrot, celery, and parsley leaves, is tempered by the beauty of its adult form.

Celeryworm

Surely the elegance and grace of the adult form, the black swallowtail butterfly fluttering about the garden, adds as much beauty as a marigold or rose.

Black swallowtail

HEAT? DROUGHT? NO PROBLEM.

/6 Comments/in Gardening, Pests/by Lee ReichPhysiological Workaround

Portulaca is a genus that gives us a vegetable, a weed, and a flower. All flourish undaunted by heat or drought, a comforting thought as I drag the hose or lug a watering can around to keep beebalm, an Edelweiss grapevine, and some marigolds and zinnias — all planted within the last couple of weeks — alive.

Portulaca employ a special trick for dealing with hot, dry weather, which presents most plants with a conundrum. On the one hand, should a plant open the pores of its leaves to let water escape to cool the plant, as well as take in carbon dioxide which, along with sunlight, is needed for photosynthesis. On the other hand, the soil might not be sufficiently moist or the pores might end up jettisoning water faster than roots can drink it in, in which case closing the pores would be the ticket.

Portulaca gets around this conundrum by working the night shift, opening its pores only in darkness, when little water is lost, and latching onto carbon dioxide at night by incorporating it into malic acid, which is stored until the next day. Come daylight, the pores close up, conserving water, and malic acid comes apart to release carbon dioxide within the plant. I describe this specialized type of metabolism in my book The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden.

From the Pampas to my Garden

Let’s start with the flower Portulaca, P. grandiflora, which goes either by a common name that is the same as the generic name, or by the name “moss rose.” In truth, the plant is neither a moss nor a rose. But the tufts of lanceolate leaves do bear some resemblance to moss, a very large moss. And portulaca’s flowers, which are an inch across, with single or double rows of petals in colors from white to yellow to rose, scarlet, and deep red, are definitely rose-like. The plant grows to a half-foot-wide mound, with stems that are just barely able to pull themselves up off the ground under the weight of their fleshy leaves.

Moss rose is native to sunny, dry foothills that rise up along the western boundary of the South American pampas. As might be inferred from its native habitat, this plant not only tolerates, but absolutely requires, full sun and well-drained soil. Such requirements, and low stature, make the plant ideal for dry rock gardens and for edging.

Moss rose is easy to grow from seeds sown at their final home, or started in flats for transplanting. Some gardeners mix the extremely fine seed with dry sand before sowing, to ensure uniform distribution.

Once blossoming begins, it continues nonstop until plants are snuffed out by frost. Moss rose is an annual, but sometimes will seed itself the next season. However, double varieties (plants with double rows of petals) grown this year will self-seed single varieties (plants with a row of petals) “volunteers” next year.

Plant It or Not, It Will Be There

The vegetable and the weedy Portulaca can be dealt with together; they are one and the same plant, P. oleracea. Somewhere in your garden now, you surely have this plant, whose succulent, reddish stems and succulent, spoon-shaped leaves hug the ground and creep outward in an ever-enlarging circle.

The common name is purslane, though it has many aliases, including pussley, Indian cress, and the descriptive Malawi moniker of “the buttocks of the wife of a chief.”

Tenacity to life and fecundity accord purslane weed status. Pull out a plant and toss it on the ground, and it will retain turgidity long enough to re-root. Chop the stems with a hoe, and each piece will take root. Even without roots, the inconspicuous flowers stay alive long enough to make and spread seeds.

My one consolation with having this weed in my garden is that it’s easy to remove, robs little nutrients or water from surrounding plants, and, being low-growing, casts little or no shade. Perhaps it even protects the soil surface from sun beating down on it or pounding raindrops from washing away soil. On the other hand, left unattended, it could take over a garden this time of year.

You Could Eat It

What about purslane, the vegetable? Take a bite. The young stems and leaves are tender and juicy, with a slight, yet refreshing, tartness. Purslane is delicious (to some people, admittedly not to me) raw or cooked, and is much appreciated as a vegetable in many places around the world besides its native India.

I have actually tasted the result of the plant’s specialized metabolism in summer by nibbling a leaf of purslane at night and then another one in the afternoon. Malic acid makes the night-harvested purslane more tart than the one harvested in daylight.

There are cultivated varieties of purslane for planting(!) in the vegetable garden. These varieties have yellowish leaves and a more upright growth habit than the wild forms. Wild or cultivated, the plants can be grown from seed or, of course, by rooting cuttings from established plants.

As far as actually planting purslane in my garden, I agree with the view of another garden writer who said “it is a reckless gardener who would plant purslane.” That does not mean that I do not grow purslane, though, for plenty keeps appearing despite my weeding.

Every once in a while, I again try eating it. I have enjoyed it in salads in restaurants to such accompaniments (or taste and texture disguisers) as feta cheese, olive oil, vinegar, and other strong flavors.

If you do opt to plant purslane, you must replant it yearly. Like the moss rose, purslane is an annual plant. Once established in the spring, both purslane and moss rose need no further care. Now, if only moss rose were a bit more weedy . . .