FORWARD, WITH FIGS

/2 Comments/in Fruit/by Lee ReichPotted Figs, but First a “Haircut”

Temperatures here have dipped into the lower 20s a few nights and still dip readily to around freezing, which might lead some of you to believe I have been neglectful of my fig trees, which are still outdoors. Not so! They are subtropical plants that can take temperatures down into the ‘teens.

Today I moved all my potted figs to their winter home. As I wrote in my book Growing Figs in Cold Climates, fig, being a subtropical plant, likes cold winters, just not those that are too, too cold. My plants went either into my basement, where winter temperatures hover in the 40s, or into my walk-in cooler (also used for storing fruits and vegetables) whose temperature is nailed at 39°.

One of my friend Sara’s figs in summer

I always prune my figs before nestling them into the basement or the cooler. Then they can be carried without errant stems slapping my face, and the pots can be stored without undo elbowing neighboring potted figs.

IN WHICH A SMALL GAS MOLECULE HAS A BIG EFFECT

/0 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichIt’s a Gas

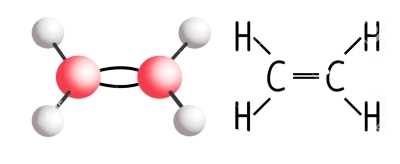

Ethylene is so simple. It’s a gas made up of merely two atoms of carbon and four atoms of hydrogen. Simple gases are generally not the kinds of molecules that make plant hormones which, like human hormones, are generally complex molecules with dramatic effects at extremely low concentrations. Nonetheless, ethylene is a plant hormone. I thought of ethylene as I sunk my teeth into the last garden-fresh peppers of the season a couple of weeks ago. Note that I wrote “fresh,” not “fresh-picked.”

Those peppers were picked week or two before being eaten. I picked any green peppers showing the slightest hints of red, then spread them out on a tray. Many gardeners do this with tomatoes. I like peppers a lot more than tomatoes so only occasionally try to prolonging the season of fresh tomatoes.

It’s ethylene that’s responsible for the transformations from unripe to ripe. Ethylene is produced naturally in ripening fruits, and its very presence — even at concentrations as low as 0.001 percent — stimulates, in turn, further ripening. The ethylene given off by ripe apples can be used to hurry along ripening of peppers or tomatoes, by placing an apple in a closed bag with them.

If the fruits are left too long in the bag, ethylene will stimulate ripening which will stimulate more ethylene which will stimulate even more ripening which will stimulate more ethylene which will stimulate still more ripening, ad infinitum, until what is left is a bag of mushy, rotten fruit. Apples can do this to each other, so one rotten apple really can spoil a whole barrel of them.

MY NEW BOOK IS OUT!!

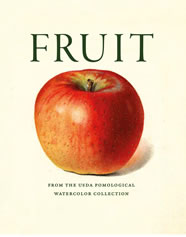

/2 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichMy newly published Fruit: From the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection (Abbeville Press, 2022), now available here as well as from the usual sources, is a fusion of art, science and history in a 4.4” x 4.7” hardcover volume of 288 pages. The pocket-sized folio is like a miniature coffee table book, a celebration of fruit-growing in an earlier America with a wealth of historical context and scientific information. The first half of the book is devoted to a range of apple varieties, many with unfamiliar and quaint names; most of these cultivars now lost to time. Subsequent chapters cover pears and other pomes, stone fruits, citrus, berries and miscellaneous fruits such as avocados, pomegranates, persimmons and nuts.

The pocket-sized folio is like a miniature coffee table book, a celebration of fruit-growing in an earlier America with a wealth of historical context and scientific information. The first half of the book is devoted to a range of apple varieties, many with unfamiliar and quaint names; most of these cultivars now lost to time. Subsequent chapters cover pears and other pomes, stone fruits, citrus, berries and miscellaneous fruits such as avocados, pomegranates, persimmons and nuts.

Here are some details:

Between 1886 and 1942, the US Department of Agriculture employed a total of 20 artists, mostly women, to paint watercolors of various fruit varieties. The seventy-five hundred luscious watercolors were used for educational and promotional purposes. And they are beautiful.

I selected 250 of the watercolors for their beauty, historical interest, and/or quaintness, and compiled them into this tiny folio. Would you reach for a Peasgood Nonesuch or Peck’s Pleasant apple, a Neva Myss peach, or (dare one say it?) a Nun’s Thigh pear from a supermarket shelf?