Here Kitty, Kitty

/2 Comments/in Gardening, Houseplants/by Lee Reich

To a Cat’s Delight

How does your cat like your houseplants? I don’t mean how they look. I mean for nibbling, a bad habit of some cats. Bad for them and bad for you because eating certain houseplants could sicken a cat, or worse, and, at the very least, leave the houseplant ragged.

One way to woo a feline away from houseplants would be to provide a better alternative. Now what could that be? Duh! Catnip, Nepeta cataria, a member of the mint family, admittedly not the prettiest of houseplants but, hey, you’re growing this for your cat, not yourself. (Other Nepeta species, such as N. x faasssennii and N. racemes, are less enticing to cats even if they are more attractive to us.)

Catnip is very easy to grow outdoors, and can be grown indoors through winter. The main ingredient that could be lacking in winter is light; six or more hours of sunlight beaming down on the plant through a window would be ideal. Other than that, needs are the same as most other plants: regular potting soil coupled with a watering regime that keeps said soil neither sodden nor bone dry, just moist.

Catnip plants are not hard to find. Growing from seed is easy, except the plants won’t be cat-ready for weeks and weeks.

Established plants are quick and easy to multiply so if you’ve got a friend with a potted plant, preferably overgrown so that you both benefit, you can make new plants by slicing the root ball into two or more new sections along with their above ground stems, and then repotting each of them. Or clip off stems each a few inches long, strip leaves from their bottom portions, and poke them into moist potting soil to root. Help these shocked plants or plant parts recover by keeping them in bright but indirect light for a couple of weeks — and protected from any cats!

Which brings me to perhaps the worst potential pest of your new catnip plant: cats! They’ll roll in it, releasing the strong aroma that drives them crazy, and nibble it to experience its narcotic effect. Outdoor plants tolerate such rambunctious playing; indoor plants, with less than perfect growing conditions, are more frail. You might want to limit playtimes to weekly visits.

Limiting playtimes might also keep the plant more enticing. Cats can habituate to catnip. And even then, only about fifty percent of cats fall under the spell of catnip, none of them as kittens.

—————————————

No reason to limit your cat’s botanical garden to catnip. Cats also like to nibble on grasses, which can be very pretty houseplants and lack the not very popular aroma (to most humans) of catnip.

It’s not clear why cats, which are carnivores, like that nibble. Perhaps, some say, to induce vomiting to get rid of undigested animal parts. Perhaps, others say, for vitamins and minerals.

“Grasses” is a term I use quite liberally, to mean not necessarily lawn grass but any plant in the grass family. Most convenient is to just mosey over to the local health food store and purchase some whole grain such as wheat (sold as “wheat berries) or rye. Soak a batch of these seeds in water for a few hours and then sow them in potting soil in a decorative container. Depending on the temperature, green sprouts should soon appear against the dark backdrop of soil. Grasses grow quickly, given light, warmth, and sufficient, but not too much, water.

The aforementioned grasses are annuals and at some point in their growth, what with cat nibbling and aging, will start looking ragged. Have another pot ready with already sprouting grass. And so on.

The grass serves well for us humans as well as our cats to enjoy. They’re very spring-like in their appearance even if confined to only a small pot, a microcosm of what’s to come.

Happy Birthday Ficus

/0 Comments/in Design, Gardening, Houseplants/by Lee Reich

Another Year, Another Pruning and Re-potting

I’d like to say it was the birthday of my baby ficus except I don’t know when it was actually born. And since it was propagated by a cutting, not by me, and not from a seed, I’m not sure what “born” would actually mean. No matter, I’m having its biannual celebration marking its age and its growth.

Just for reference, baby ficus is a weeping fig tree (Ficus benjamina), a tree that with age and tropical growing conditions rapidly soars to similar majestic proportions as our sugar maples. That is, if unrestrained in its development.

Baby ficus (FIGH-kus) began life here as one of three small plants rooted together in a 3 inch pot and purchased from a discount store. (Weeping figs are common houseplants because of their beauty and ability to tolerate dry air and low light indoors.) Eight years later, it’s about 4 inches tall with a wizened trunk and side branches that belie its youth.  Moss carpeting the soil beneath it and creeping up the trunk complete the picture. I’ve made and am making baby ficus into a bonsai.

Moss carpeting the soil beneath it and creeping up the trunk complete the picture. I’ve made and am making baby ficus into a bonsai.

The biannual celebration begins with my clipping all the leaves from the plant. Baby ficus’ diminutive proportions keep this job from being tedious. Clipping the leaves accomplishes two goals. First, plants lose water through their leaves so removing leaves reduces water loss (important in consideration of the next celebratory step).

Clipping the leaves accomplishes two goals. First, plants lose water through their leaves so removing leaves reduces water loss (important in consideration of the next celebratory step).

And second, clipping the leaves reduces the size of leaves in the next flush of growth, keeping the in proportion to the size of the plant. Leaves on an unrestrained weeping fig grow anywhere from 2 to 5 inches long, which would look top heavy on a plant 4 inches tall.

The next step is to tip the plant out of its pot so I can get to work on its roots. The pot is only an inch deep and 4 inches long by 3 inches wide, so obviously can’t hold much soil.  Baby ficus gets all water and its nourishment from this amount of soil. Within 6 months or so, roots thoroughly fill the pot of soil and have extracted much of the nourishment contained within.

Baby ficus gets all water and its nourishment from this amount of soil. Within 6 months or so, roots thoroughly fill the pot of soil and have extracted much of the nourishment contained within.

So the roots need new soil to explore, and space has to be made for that new soil. That space is made by cutting back the roots. (Less roots means less water up into the plant, which is why I began by reducing water loss by clipping off all the leaves). I tease old soil out from between the roots and with a scissors shear some of them back.

Next, I put new potting mix into the bottom of the pot, just enough so the plant can sit at the same height as it did previously. Any space near the edges of the pot gets soil packed in place with a blunt stick. Throughout this repotting, I manage to preserve more or less intact the moss growing at the base of the plant.

Now the plant needs its stems pruned. After all, I don’t want the plant growing larger each year, just more decorative as the trunk and stems thicken and age. Pruning involves some melding of art and science. As far as art, I’m aiming for the look of a mature, picturesque tree.  As far as science, I shorten stems where I want branching, usually just below the cut. Where I don’t want branching but want to decongest stems, I remove a stem or stems right to their base. I also remove any broken, dead, or crossing branches unless, of course, leaving them would be picturesque.

As far as science, I shorten stems where I want branching, usually just below the cut. Where I don’t want branching but want to decongest stems, I remove a stem or stems right to their base. I also remove any broken, dead, or crossing branches unless, of course, leaving them would be picturesque.

Finally, a thorough watering settles the plant into its refurbished home. Until new leaves unfold and new roots begin to explore new ground, water needs for baby ficus are minimal.

Oh, one more step. I stand back and take an admiringly look at baby ficus in its eighth year.

Fahrenheit Obsession

/11 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichA Pillbox Relaxes Me

A little blue pillbox has solved my sleep problems.

I’ve touted the abundance of fresh figs I gather in summer and fall from my greenhouse, and the salad greens in winter. Not to mention the transplants for the garden in spring and summer.

All this has come at a price: sleep. In winter I often worry that something will go awry with the heater that keeps greenhouse temperatures from dropping below freezing, threatening the life of the in-ground fig trees and the salad greens.

And things have occasionally gone awry. One winter, the gas company didn’t deliver the gas for the propane heater on time. Another winter the pilot light kept going out on the heater. Another winter there was an interruption in electrical service, just a small amount of which is needed for the thermostat.

From the warmth of my home, how could I know if my plants were suffering so that I could take action? I set up a remote monitor with a secondary thermostat and a light bulb; if the greenhouse temperature drops below 35° F., I know it because the light goes on. Of course, I have to look outside at the greenhouse occasionally. And if I’m in bed on some cold winter night . . . a bicycle mirror mounted on the window lets me know if the light is on without my even having to lift my head. Of course, all bets if I am asleep, or if electrical service is interrupted.

Which brings me back to the blue pillbox. It’s filled with electronics, not pills.

SensorPush in greenhouse

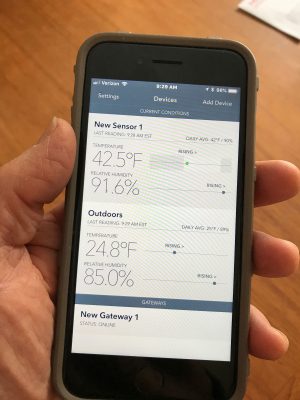

This device, sold as SensorPush, hangs on a nail in my greenhouse and continuously records temperature and humidity therein. No need for me to go to the greenhouse to communicate with it, though. It beams the information via bluetooth to my smartphone.

Better still, I can retrieve the information if my phone is beyond the approximately 325 foot bluetooth range with the help of the SensorPush Gateway. The Gateway connects via wi-fi to put the temperature and humidity information on the web and then on to my smartphone. From anywhere that I have cell service.

The Gateway connects via wi-fi to put the temperature and humidity information on the web and then on to my smartphone. From anywhere that I have cell service.

And even better, SensorPush can also alert my smartphone (and, hence, me) should the greenhouse temperature ever drop below (or above) whatever low (or high point) I set it at. The Gateway does require electricity. But Central Hudson has an alert feature to notify me, again via my increasingly smart smartphone, if the electrical service has been interrupted.

Checking Out the Weather, Continuously

I’m going to get another SensorPush to hang outdoors on one of the garden fenceposts. Knowing temperatures and humidity out in the garden is very useful to anyone who grows tree fruits.

Spring frosts threaten blossoms of fruit trees that bloom early in the season. Most threatened are apricots and peaches, but a season’s crop of apples, pears, cherries, or plums could also be snuffed out by a dramatic drop temperature.  Just how much cold kills these blossoms depends on the kind of fruit and the stage of blossoming. For instance, when apricot flower buds have just begun to swell and separate, they’ll laugh off cold down to zero degrees F. Once the petals begin to spread, the buds are killed at 19°F. When petals fall, 24° is lethal.

Just how much cold kills these blossoms depends on the kind of fruit and the stage of blossoming. For instance, when apricot flower buds have just begun to swell and separate, they’ll laugh off cold down to zero degrees F. Once the petals begin to spread, the buds are killed at 19°F. When petals fall, 24° is lethal.

So a SensorPush out in the garden would at the very least tell me whether to expect a crop from any of these tree fruits. Or to take action, like running outside to drape a blanket over a tree.

Knowing temperature and humidity can also predict the likelihood of disease. The spores of brown rot disease of plums, for instance, grow best in rainy weather with temperatures in the mid-70s during bloom or as fruit is ripening. Longer periods of wetness are needed at lower temperatures. Once again, such information can be used for prediction or action, in the latter case a preventative spray of sulfur, for example. (Sulfur, a naturally mined mineral, is an organically approved fungicide.)

A final nice feature of SensorPush is that it keeps records of the data it collects. The graphs it generates can be viewed on my smartphone or downloaded to a computer.

Now . . . if only I had an expensive art collection, a wine cellar, a reptile cage, or something else that needed close monitoring of temperature and humidity, I could justify another SensorPush.

Okay, now I’m going back to sleep, soundly.