Snowy Skies & Winter Colors

/5 Comments/in Flowers, Vegetables/by Lee ReichSnow Outside but Color Inside

A day like this, a gray sky and six inches of fluffy, fresh snow laid gently atop the white already resting on the ground, hardly turns my mind to gardening or plants. Even the greenhouse, usually a cheery horticultural retreat in winter, is dark and cold. Snow on the roof blocks what little light peeks through the gray sky, and the heater doesn’t come alive until the temperature drops to about 37° F.

Carrots from jonnyseeds.com

And then I reach into my mailbox, and out comes summer! Seed and nursery catalogs oozing with photos of fresh carrots, heads of lettuce, juicy peaches, and sunny sunflowers. I’ve already ordered all my seeds, or so I thought until I started thumbing through more catalogs. Offerings in vegetable seeds, in particular, seem to get more interesting each year.

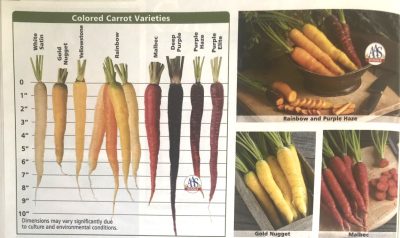

Take carrots, for example. Carrots have long been available in all sort of shapes and sizes. Nowadays, I can also buy seeds for white carrots (White Satin variety), carrots deep purple through and through (Deep Purple variety), and purple carrots with orange centers (Purple Haze variety).

Caulifower is also getting colorful. Its curds no longer need to be only white. The variety Cheddar is the color of orange cheddar cheese. Graffiti is a purple variety, unique among purple cauliflowers for retaining its color after being cooked. Years ago, I used to grow Violet Queen cauliflower, which turns green after being cooked and tastes very good.

I’m not saying that any of these interesting varieties taste better than less flamboyant varieties. Just sayin’ . . . they’re interesting.

Which Hazel?

Besides perusing summer-y seed and nursery catalogs, another antidote for a gray winter day is to get outside and enjoy it. I’m hoping to do that today, to glide through wooded paths on cross-country skiis.

No doubt I will come across plants flaunting winter weather and showing signs of life —even on this gray day. Native witchhazels, the so-called “common witchhazel” (Hamamelis virginiana), ocacionally still are showing off some of their strappy yellow flower petals.  The flowers don’t exactly jump out at you so you have to get up pretty close to even notice them. Still, they are a sign of plant life in the depths of winter.

The flowers don’t exactly jump out at you so you have to get up pretty close to even notice them. Still, they are a sign of plant life in the depths of winter.

Common witchhazel typically begins blooming in September and finishes by December. How seemingly foolish! It’s been hypothesized that they bloom when they do so as not to compete with another species, vernal witchhazel (H. vernalis), where both are native. (This seems an unusual explanation because plant evolution is generally encouraged by cross breeding. That’s why an apple tree, for instance, can’t pollinate itself even though each of its flowers have both male and female parts; it has to cross with pollinate with a genetically different tree to make seeds and fruit.) Vernal witchhazel, at home in the midwest and south, begins blooming in January and might continue until spring.

Even without that competition, not much reproduction is going on with common witchhazel. It has a motley crew of pollinators: tiny wasps, fungus gnats, bees, flies, and winter moths. And even with all those matchmakers, less than 1% of flowers go on to form fruit and make seed. The seeds, 2 per fruit, are shot out of the fruits in autumn. After weevils, caterpillars, wild turkeys, and squirrels have had their fill, only about 15% of those few seeds survive. It’s a wonder that I come upon so many witchhazels in my winter glides and walks.

Looking over plant and garden notes from last year, I see that my cultivated witchhazel, the variety Arnold Promise, bloomed in my front yard in mid-March last year. That variety is a hybrid of Chinese and Japanese species. It blossoms later and its blossoms are much, much showier and more fragrant.

Sow Already?

Last year, sowing onion seeds

According to my notes, I’m due to plant onion seeds sometime soon. Yes, seeds. Seeds are the only way to be able to choose from the widest selection of onion varieties. Still, seeing witchhazel flowers will not be enough to well up in me an urge to plant anything. Tomorrow will be sunny; that should do it.

Update: Except that I chose the sunny day to go skiing instead. The onion seeds can wait. Growth is so slow early in the season that, come early May, there’s little difference in size among seedlings grown from seed planted now or within the next couple of weeks.

Cold Rules

/9 Comments/in Gardening, Planning, Soil/by Lee ReichWater Freezes. Why Don’t Plants?

(The following is adapted from my book, The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden, available wherever fine books are sold, and my website.)

Not being able to don gloves and a scarf, or shiver, to keep warm, it’s a wonder that trees and shrubs don’t freeze to death from winter cold. They can’t stomp their limbs or do jumping jacks to get their sap moving and warm up. The sap has no warmth anyway.

Sometimes, of course, plants do succumb to winter cold. But usually that happens to garden and landscape plants pushed to their cold limits, not to native plants in their natural habitats or to well adapted exotic plants.

Think about it: water freezes at 32 degrees Fahrenheit—not a particularly cold temperature for a winter night—and plants contain an abundance of water. Water is unique among liquids in that it expands when it freezes, so you can imagine the havoc that could be wreaked as water-filled plant cells freeze and burst. Yet plants that must stand tall all winter do, of course, deal with frigid weather.

A Helping Hand for Herbaceous Plants

Herbaceous perennials (non-woody plants) opt for the easiest survival route.Their roots are perennial but their tops die back to the ground each year. Anticipate cold weather, these plants start pumping reserve nutrients to their roots in late summer. That’s why asparagus, cone flowers, delphiniums, and peonies are reduced, in autumn, to nothing more than a few dry stalks.

What’s left of these plants spends a mild winter underground. Five feet down, the earth’s temperature hovers around a relatively balmy 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

Practical Rule #1: A thick blanket of some fluffy, organic material—leaves, straw, or wood chips, for example—further limits cold penetration.

Also for Woody Creepers

Low-growing, woody plants have it almost as good, with their stems shielded from the full brunt of cold winter winds. If Nature decides to throw down a powdery, white insulating blanket, so much the better: those leaves and low stems are protected even more.

Practical Rule #2: In case Mother Nature is distracted with other activities, I provide my own low blanket for low-growing, woody or evergreen perennials—again, that fluffy cover of straw, leaves, or wood chips. Waiting to cover these plants until the weather turns relatively cold (soil frozen an inch deep is a good rule of thumb) lets plants acclimate to cold, and their stems and leaves have no chance of rotting beneath mulch that is still moist and too warm.

Tricks and Tips for Trees and Large Shrubs

What about trees and shrubs whose stems are fully exposed. One way they protect themselves from freezing is by shedding those parts most likely to freeze—their leaves.

Which introduces Practical Rule #3: I help plants along with their leaf shedding by letting plants naturally slow down and begin to reallocate their energy resources beginning in late summer. No water, fertilizer, or pruning at that time.

Of course, their stems still have to stand up and face the cold. Their living cells are filled with water. If this water freezes, the cells either dehydrate or suffer physical damage from ice crystals.

Water, whether in a plant cell or a glass, does not necessarily freeze as soon as the temperature drops below 32 degrees Fahrenheit. To freeze, water molecules need something to group around to form ice crystals, a so-called nucleating agent. Otherwise it “supercools,” remaining liquid down to about minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit, at which point ice forms whether or not a nucleating agent is present.

All sorts of things can serve as nucleating agents—bacteria, for instance—so plants may not be protected all the way down to minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit by having their water supercool. But winter temperatures don’t plummet that low everywhere, so just a bit of supercooling may be all a plant needs to survive winter cold.

Another trick, effective well below that minimum supercooling temperature, is for a plant to gradually move water out of its cells into spaces between the cells. As temperatures drop, ice crystals outside plant cells grow with the water they draw out of the cells; plants then are threatened by dehydration than by freezing. Plants toughest to cold are those that are best at reabsorbing the water outside their cells when temperatures warm.

One other mechanism at work “freezing point depression,” which is why antifreeze keeps the water in your car radiator from freezing. Dissolving anything in water lowers the freezing point, more so the more that’s dissolved. As liquid in plant cells lose water, remaining water becomes more and more concentrated in sugars and minerals, its freezing point keeps falling.

Plants actively prepare for cold, with cell walls increasingly strong and and permeable. Light supplies needed energy for all this, making Practical Rule #4 to make sure to site and prune plants for adequate light.

Unfortunately, all this fiddling with a plant to help it through winter palls in the face of genetics. The very most that I can do to help plants face winter is to plant those that naturally tolerate the coldest temperatures winter is apt to serve up.

Get Crackin’

/11 Comments/in Fruit/by Lee ReichCured!

It’s finally time to get crackin’. Literally. Black walnuts are ready for shelling.

This nutty story goes back to early this past autumn as black walnut trees were shedding their nuts. The nuts fall in their husks, the whole package looking like green tennis balls. Lots of people curse the trees for littering lawns, sidewalks, and driveways. We, on the other hand, praise and collect the nuts.

The first step to the present day crackin’ was husking the nuts. The soft, fleshy covering is easy to twist off the enclosed, hard-shelled nut. But we’ve also tried many methods to speed up the process, from spreading the dropped fruit in the driveway and driving over them to pounding them through a 1-1/2” hole in a thick piece of plywood to running them through a suitably modified old-fashioned corn-sheller.

There’s no way around it: Husking black walnuts is a tedious job. And messy, because the soft flesh readily releases a juice which stains everything a deep brown color.

A friend recently told me of some novice black walnut enthusiasts that husked the walnuts bare handed, assuming the stain would wash off when they were finished. Not so. My wife Deb, who husks our black walnuts, chooses to sit herself down on a stool, don rubber gloves, and twist off the hulls, coaxing firm ones off with an initial tap with a light sledge hammer.

(The stain, which is colorfast and resistant to ultraviolet rays, is very easy to extract from the hulls for ink, for dyeing textiles, and staining wood. Just mix the hulls or unhulled nuts with water and boil for awhile or let sit a longer while. Strain and you’re good to go.)

In not too long, we had a number of 5 gallon bucketfuls of hulled nuts — a slimy, ugly mess from bits of hull still attached to the nuts and from the myriad white maggots crawling.

Now it was my turn — to clean up the nuts. I loaded all the nuts into shallow harvest boxes that had plenty of large holes for air or water and drove over to a nearby car wash. After suiting up in an old pair of rain pants, a rain jacket, rubber gloves, and a face shield, and spreading out the boxes on the ground in the car wash, I gave them a thorough, water-only cleaning.

I then spread the boxes out in the sun for a couple of days to dry out the surface of the nuts. Squirrels would be a serious threat but I spread the boxes on our south-facing deck where our two dogs also spend much of the day unknowingly guarding the nuts. Each night, or if any rain was predicted, I stacked and covered the boxes.

After the nuts were sufficiently dry, I stacked the trays in the barn where our cat is the squirrel deterrent.

Then the nuts needed to be cured, which involves nothing more than leaving them alone in a cool, dry, squirrel-fee area. And that brings us up to the present day.

A Tough Nut

Black walnut is a hard nut to crack. No run-of-the-mill nutcracker is up to the job. The usual tool, which is effective, is a hammer against the nut resting on an anvil or concrete. Used with care, a vise might do the job.

Two problems: With the hammer, hitting your finger occasionally as you hold the nut is inevitable. You could, I guess, hold the nut in a pliers. With either method, you have to use just the right amount of force to crack the shell sufficiently in order to extract the nutmeats in reasonable sized pieces without crushing everything too, too small.

The hands-down best job for cracking black walnuts is, in my opinion, the “Master Nut Cracker” (http://www.masternutcracker.com). It’s expensive but well worth the money for the speed with which the nuts can be cracked and the large nutmeats that result from efficient cracking. Besides which, it’s a very well-made tool with a very ingenious design.

Once nuts are cracked, nutmeats still occasionally need further coaxing to free them from the shell. A useful tool that I use that almost everyone has is a type of wire cutter sometimes called a diagonal cutting plier. The right squeeze in the right place, the result of observation and practice, yields large nutmeats that pop right out.

But Is It For You?

Black walnuts have a strong flavor that, like dark beer and okra, is loved by some but not enjoyed by everyone. But there’s no reason why everyone should like everything. Leave that goal to MacDonald’s. As L. H. Bailey, a doyen of horticulture, wrote back in 1922 (about apples), “Why do we need so many kinds of apples? Because there are so many kinds of folks. A person has a right to gratify his legitimate tastes.”

Black walnut is one of my favorite nuts. And, the trees and nuts abound around here, and elsewhere, free for the taking.