SOMETHING A LITTLE DIFFERENT, IN FRUIT

/13 Comments/in Fruit/by Lee Reich(Adapted from my book Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden, now out of print but very soon available as online version. Stay tuned. Information is also available in my books Grow Fruit Naturally and Landscaping with Fruit, available from my website and the usual sources.)

I always know when my hardy kiwifruits are ripe because my dogs and ducks start grubbing around beneath the vines for drops. The fruits, for those unfamiliar with them, are similar to the fuzzy kiwifruits (Actinidia deliciosa) of our markets, only much better for a number of reasons.

Obviously, from the name, hardiness is one reason. Hardy kiwifruits will laugh off cold below even minus twenty-five degrees Fahrenheit, while market kiwis are injured below zero degrees Fahrenheit.

Another difference is in the fruit itself. Hardy kiwifruits are grape-size, with smooth, edible skins. Pop them into you mouth just as with grapes. Within the skin, hardy kiwifruits look just like market kiwis, in miniature. The flavor of hardy kiwifruits, though, is far superior to that of the fuzzies, sweeter and with more aroma.

Okay, I have to qualify that last statement because there are actually two different species of fuzzy kiwifruits. A. chinensis, rarely seen for sale outside China, is relatively large (though usually not as large as A. deliciosa) with skin covered by only a peach-like fuzz. The flesh color ranges from green to yellow, on some plants even red, in the center. The flavor is very sweet and aromatic, smooth and somewhat tropical, reminiscent of muskmelon, tangerine, or strawberry. In all honesty, this kiwifruit has the best flavor of all — but it’s even less cold hardy than the more common fuzzy, market kiwifruit. If winter temperatures here were mild enough for me to grow A. chinensis, I would.

Two Species, One Flavor

Hardy kiwifruits also come in two species: A. kolomikta and A. arguta. But not two flavors; they taste pretty much the same.

Both are ornamental vines, so much so that they were originally introduced into this country from Asia over 100 years ago strictly for their beauty, their innocuous fruits overlooked. How many visitors pass beneath the many handsome vines planted early in the twentieth century on public and private estates, unaware of the delectable fruits also hidden beneath the foliage?

For most kiwifruits, male and female flowers are borne on separate plants. Only the females bear fruit, but males are needed for pollen to get that fruit to form. (Just like humans and most animals, the “fruit” in animals being the ovary responding to fertilization.) One male (kiwi plant) can sire up to about eight females.

The two species of hardy kiwifruits do have their differences. The one that’s ripe for me now is A. kolomikta, which I choose to call the super-hardy kiwifruit because it’s cold-hardy to below minus forty degrees F. (For a pleasant dance of your tongue, sound out and speak the species name slowly.) Kolomikta is the more strikingly ornamental of the two because of the pink and silvery variegation of its leaves.  This species is also relatively sedate in growth, so is easier to manage. One problem with this fruit, which my ducks and dogs consider a plus, is that it drops when it is ripe, perhaps because it’s ripening so quickly during hot days of summer.

This species is also relatively sedate in growth, so is easier to manage. One problem with this fruit, which my ducks and dogs consider a plus, is that it drops when it is ripe, perhaps because it’s ripening so quickly during hot days of summer.

The other species, A. arguta, is more sedately ornamental, with apple-green leaves attached to the vines on reddish leaf stalks. Fruits of this species, depending on the variety, start ripening in the middle of September, and they stay firmly attached. One problem with A. arguta, mostly for casual growers, is that it’s much less sedate in growth. My vines send out a number of 10 foot long canes every year.

Must You Prune?

Pruning keeps either species productive and within bounds. Containing the plant is especially important with A. arguta. A number of years ago, I gifted two plants to a friend. He planted them at the base of a sturdy arbor that was attached to his front door. I’m not sure he ever pruned the plant, and 15 years later the arbor was on the ground.

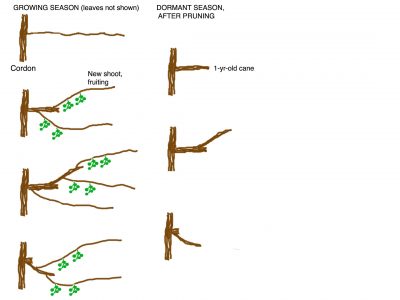

Still, either species grows best trained to some sort of structure. Mine, which are grown mostly for fruit, are trained on a series of T-shaped posts fifteen feet apart and joined at their cross-members by five equally spaced wires. Each plant’s strongest shoot has been trained to become a trunk that reaches the center wire, then bifurcates into two permanent arms, called cordons, running in opposite directions along the center wire.

Each plant’s strongest shoot has been trained to become a trunk that reaches the center wire, then bifurcates into two permanent arms, called cordons, running in opposite directions along the center wire.

Fruiting canes grow off perpendicularly to the center wire and drape over the outside wires. Flowers and, hence, fruits are borne only toward the bases of shoots of the current season that grow from the previous year’s canes, very similarly to grape vines.

Annual winter pruning entails, first, pruning off any new shoots forming anywhere along or at the base of the trunk, and shortening cordons once they have reached full length. Fruiting arms give rise to laterals that fruit at their bases; during each dormant season, cut these laterals back to about eighteen inches in length. Remaining buds on the laterals will grow into shoots that fruit at their bases the following summer. The winter after they have fruited, these shoots correspondingly should be shortened to about eighteen inches, but leave only one of these. When a fruiting arm with its lateral, sublateral, and subsublateral shoots is two or three years old, it’s cut away to make room for a new fruiting arm.

With all this said, the vines do fruit with no more pruning than a yearly, undisciplined whacking away aimed at keeping them in bounds. Such was the objective in pruning those hardy kiwifruits planted as ornamentals on old estates. These vines happily and haphazardly clothe pergolas with their small, green fruits hanging—not always easily accessible or in prodigious quantity—beneath the leaves.

Note to plant nativists: I am aware that Actinidia species are considered to be non-native invasives in many areas. I’ve grown and watched this plant for decades and have never found it growing anywhere but where I planted it. As far as I can tell, the only way this plant can spread would be for it to be planted near enough to tree stands to give the vine leg up and then to be totally neglected. I have never seen a self-sown seedling pop up anywhere.

FINAL REMINDER FOR BLUEBERRY GROWING WORKSHOP WEBINAR ON AUG. 12, 2020, FROM 7-8:30 PM

/2 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichFinal reminder for my zoom Blueberry Growing Workshop/Webinar on August 12, 2020 from 7-8:30 pm EST. I’ll cover everything from planting right through harvest and preservation. If you’re new to growing blueberries, you’ll learn how to grow this fruit successfully. If you already grow blueberries, you’ll be able to grow them better. If you’re an expert on growing blueberries, you don’t need this workshop/webinar. Registration ($35) at https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_NSTrunuTRkOcRfS-frQuYg. For more information, go to https://leereich.com/workshops.

BLUEBERRIES AND ASPARAGUS (SEPARATELY)

/25 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichAll Good

I’ve never met a blueberry I didn’t like. Then again, I have yet to taste a rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium asheii), native to southeastern U.S. and highly acclaimed there. I also have yet to taste Cascades blueberry (V. deliciosum), native to the Pacific northwest. With “deliciosum” as its species name, how could it not taste great? And those are just two of the many species of blueberry that I’ve never tasted that are found throughout the world.

The blueberries with which I am most familiar are those that I grow, which are highbush blueberry and lowbush blueberry. I grow blueberries because they are beautiful plants, because they are relatively pest free, because they are delicious, and because they fruit reliably for me year after year.

The blueberries with which I am most familiar are those that I grow, which are highbush blueberry and lowbush blueberry. I grow blueberries because they are beautiful plants, because they are relatively pest free, because they are delicious, and because they fruit reliably for me year after year.

I have to admit that highbush blueberries, at least to me, all taste pretty much the same. They have nowhere the broad flavor spectrum of apples. Tasting the same is fine with me; as I wrote, they are delicious. Depending on the variety, the berries do vary in ripening season, size, and other less obvious characteristics. One very important influence on flavor is how they are picked. Blueberries turn blue a few days before they are at their peak flavor, which is okay if you’re marketing them and just want them blue. But the best tasting tasting, dead-ripe ones are those that drop into your hand as you tickle a bunch of berries, which makes a good case for growing them near your back door.

Lowbush blueberries also taste pretty much the same from plant to plant, but their flavor is decidedly different from that of highbush blueberries, a more metallic sweetness. Few varieties of lowbush blueberry exist, so most plants are just random seedlings anyway. Not to disparage that, though; they’re also all delicious — if picked at the right moment.

A Different Blueberry

My idea that all highbush blueberries taste pretty much the same was recently challenged. New highbush varieties have been bred or selected since this native fruit went, over the past 100 years, from being harvested from mostly from the wild to being mostly cultivated. Over the years I’ve been very pleased with the nine varieties I had been growing, spreading out the harvest season from late June until early September.

Then the new variety, Nocturne, bred by Dr. Mark Ehlenfeldt of the USDA, caught my eye. Besides being billed as having unique flavor, Nocturne was also said to be notable for its jet-black fruits which, before they turn jet black, are vivid red-orange in color. What attracted me wasn’t the fruit’s unique colors, but its allegedly unique flavor atypical, so the description read, of either rabbiteye [which is in Nocturne’s lineage] or highbush.”

So I called Mark to learn more about the variety. One of the original breeding goals back 25 years ago, when Nocturne’s carefully selected parents were mated, was to get a rabbiteye variety that, blooming later than most, would be less susceptible to spring frosts. Chemically, two significant differences between rabbiteye and highbush blueberries are their organic acids. Rabbiteyes have mostly malic and succinic acids, yielding a flatter taste profile than highbush fruits, whose citric acid makes for a brighter, sharper flavor. Other species were also thrown into the mix, including Constable’s blueberry (V. constablaei), a native of higher elevations in southeastern U.S., and contributing late blooming and excellent flavor.

Long story short: Nocturne is significant for being a variety with significant rabbiteye parentage that is winter hardy to well below zero degrees Fahrenheit and late blooming. It has excellent flavor, juicy sweet, and sprightly, and quite different from my other highbush varieties. Nocturne tastes even juicier than it is. Which do I like better? Neither, I like them all. Nocturne, now in its third year here on the farmden, now has a permanent place in my Blueberry Temple.

Blueberry Temple

Learn the Ins and Outs of Growing Blueberries

If you have the space, grow blueberries. To that end, I will be holding a zoom workshop/webinar on growing blueberries on August 12, 2020 from 7-8:30 pm EST. I’ll cover everything from planting right through harvest and preservation. If you’re new to growing blueberries, you’ll learn how to grow this fruit successfully. If you already grow blueberries, you’ll be able to grow them better. If you’re an expert on growing blueberries, you don’t need this workshop/webinar. Registration ($35) is a must as space is limited; registration link is

https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_NSTrunuTRkOcRfS-frQuYg. For more information, go to https://leereich.com/workshops.

Asparagus Redux

On a totally different topic, I’d like to followup on my end-of-harvest-season treatment of asparagus. Weeds have always been somewhat problematic in my asparagus bed. Harvest ceases at the end of June so plants can grow freely and feed energy to the roots which will fuel the following year’s spears in spring. Weeds quickly move into this hard-to-weed area.

As I wrote on this blog a few weeks ago, this past June, at the end of asparagus harvest season, I mowed everything, weeds as well as emerging asparagus spears, to the ground with my scythe. I then blanketed the ground with a thick mulch. I first laid down an inch depth of compost, which will feed the soil as well as smother roots, and then topped that with another inch or two of wood chips.

There was the danger of smothering the emergence of new asparagus shoots, but plenty have pushed up through the mulch.

As far as weeds, there are very few. Most of them appear at the grassy edge of the bed.

Success!