Seeds Want to Grow

Yes, They Want To, But . . .

Today, as I was carefully planting a bed with turnip, arugula, and mustard seeds, I got to thinking how easy it is to grow plants from seeds. It’s not surprising. After all, seed plants evolved millions of years ago and over the years have further evolved to germinate and grow under varied conditions. This would be especially true of those plants we call weeds.

So, with all that evolution backing me up, why the great care in planting those seeds today? Seeds do want to grow, but extra care increases the chances for success. The threats to germination and growth are competition from weeds, temperatures that are too warm or not warm enough, old seed, and insufficient soil fertility, air, or moisture. That’s not all, of course; there’s too many salts in a soil (and not just NaCl “salt”), seed-eating animals, and infections from pathogenic fungi.

Whew! That list makes growing from seed seems fraught with roadblocks. But it’s not.

Steps to Improved Germination and Growth

My extra care in planting began back last autumn when I spread an inch depth of compost on top of the bed right after clearing it of garden plants and weeds. That compost provides nutrients, beneficial microbes, and increases aeration and water retention.

Earlier this season, the bed had been home to bush beans. Bean roots, left in the soil to rot, will provide further fertility — mostly nitrogen — for today’s planting.

The bean plants, and a few weeds, were cleared from the bed a couple of weeks ago, still too early for today’s planting of fall crops. While the ground was waiting, I covered it with a black tarp. The tarp, an old billboard sign (from www.billboardtarps.com and reusable for years) that is black on its back side, stimulated growth of ever present weed seeds in the soil. The seeds germinated, then died from lack of light beneath the tarp.

After year upon year of compost applications, the soil has very good tilth, so all it needed, once I removed the tarp, was a light raking to present a loose seedbed. Into it, with a trowel, I carved the first furrow the length of the bed.

Depth of planting is important. An oft-repeated rule of thumb is that the depth to sow seeds is twice their thickness. Not true! Correct planting depth needs to also take into account the looseness of the soil; looser soil, more depth. And anyway, the seeds that I planted are only about 1/32” in diameter, making it well nigh impossible to make a furrow 1/16” deep. In my loose soil, that depth would dry out too quickly. I went with the less precise “sow shallowly.”

Garden plants grown from seed can suffer from competition not only from weeds, but also from each other. True, the young seedlings could be thinned out if too crowded after germination. With seed less than two years old and care in planting, I was confident about germination, so sowed the seed thinly.

After sowing the seeds and covering them came the all-important firming of the soil. The removal of the bean plants and the pre-plant raking to smooth the surface left plenty of large pores, through which water would run right through.

Tamping down the soil with a garden rake over the covered furrow tightened up the pores so that they can hold capillary water. Remember high school chemistry class (or was it biology class) when water was shown to be drawn up into a capillary tube against the force of gravity? Firming the soil keeps moisture around the newly sown seeds; plus, water can be drawn upwards or sideways to that area. Weed seeds, sitting in still loose soil beyond the tamped area, won’t have such an easy time of it.

Finally, I watered — thoroughly enough for the water to penetrate but, to avoid washing away the seeds, not too fast. My vegetable garden has drip irrigation; I moved the drip line up right next to where the furrow was. Frequent watering is needed until seeds germinate and their new roots reach the wetting from down in the soil. An electronic moisture probe can indicate how deep moisture lies beneath the surface.

And Now for a Flower, or Is It a Vegetable?

Many years ago I grew cardoon, a vegetable whose 3-foot-high stalks are something like celery on steroids.  The flavor hints of artichoke, a close relative. None the less, for me the flavor was awful and the stalks were tough. (Cardoon is usually covered to blanche them a few weeks before harvest. Blanching did not make mine more edible.)

The flavor hints of artichoke, a close relative. None the less, for me the flavor was awful and the stalks were tough. (Cardoon is usually covered to blanche them a few weeks before harvest. Blanching did not make mine more edible.)

Yet I am now enamored with this plant — not for eating but for its thistle-like flower. Cardoon is a perennial that begins to bloom in its second year, after experiencing a period of cool temperatures in winter. Cool, not frigid; cardoon is not cold hardy here in the Hudson Valley.

Last summer I planted seed and grew the plant in pots. Those pots spent the winter in my greenhouse, where temperatures never dipping below 35° F. reminded them of their Mediterranean origin. Once warm weather settled in this spring, I planted them out in my flower garden.

The bud on one plant that has been slowly unfurling is well worth the care I put into the plants.

Five years ago, I had the opportunity to test some of the varieties from Dr. Tom Molnar’s filbert breeding program at Rutgers University; these plants are now old enough to bear. Being test plants, they have unappetizing names like CR x R11P07 and CR x RO3P26. Mmmm. I’m sure they mean something to Tom.

Five years ago, I had the opportunity to test some of the varieties from Dr. Tom Molnar’s filbert breeding program at Rutgers University; these plants are now old enough to bear. Being test plants, they have unappetizing names like CR x R11P07 and CR x RO3P26. Mmmm. I’m sure they mean something to Tom. Yamhill always has some blight but still manages to bear nuts, small to medium-sized ones.

Yamhill always has some blight but still manages to bear nuts, small to medium-sized ones.

Occasional, light sprinklings of soil add bulk to the finished mix. Occasional, sprinklings of ground limestone keep planted ground, final stop for the compost, in the right pH range.

Occasional, light sprinklings of soil add bulk to the finished mix. Occasional, sprinklings of ground limestone keep planted ground, final stop for the compost, in the right pH range.

I train my tomato plants to stakes and single stems, which allows me to set plants only 18 inches apart and harvest lots of fruit by utilizing the third dimension: up. At least weekly, I snap (if early morning, when shoots are turgid) or prune (later in the day, when shoots are flaccid) off all suckers and tie the main stems to their metal conduit supports.

I train my tomato plants to stakes and single stems, which allows me to set plants only 18 inches apart and harvest lots of fruit by utilizing the third dimension: up. At least weekly, I snap (if early morning, when shoots are turgid) or prune (later in the day, when shoots are flaccid) off all suckers and tie the main stems to their metal conduit supports. I lop wayward shoots either right back to their origin or, in hope of their forming “spurs” on which will hang future fruits, back to the whorl of leaves near the bases of the shoots.

I lop wayward shoots either right back to their origin or, in hope of their forming “spurs” on which will hang future fruits, back to the whorl of leaves near the bases of the shoots. Newly planted trees and shrubs are another story. This first year, while their roots are spreading out in the ground, is critical for them. I make a list of these plants each spring and then water them weekly by hand all summer long unless the skies do the job for me (as measured in a rain gauge because what seems like a heavy rainfall often has dropped surprisingly little water).

Newly planted trees and shrubs are another story. This first year, while their roots are spreading out in the ground, is critical for them. I make a list of these plants each spring and then water them weekly by hand all summer long unless the skies do the job for me (as measured in a rain gauge because what seems like a heavy rainfall often has dropped surprisingly little water). Not only vegetables get this treatment. Buy a packet of seeds of delphinium, pinks, or some other perennial, sow them now, overwinter them in a cool place with good light, or a cold (but not too cold) place with very little light, and the result is enough plants for a sweeping field of blue or pink next year. Sown in the spring, they won’t bloom until their second season even though they’ll need lots of space that whole first season.

Not only vegetables get this treatment. Buy a packet of seeds of delphinium, pinks, or some other perennial, sow them now, overwinter them in a cool place with good light, or a cold (but not too cold) place with very little light, and the result is enough plants for a sweeping field of blue or pink next year. Sown in the spring, they won’t bloom until their second season even though they’ll need lots of space that whole first season. Every time I look at a weed, I’m thinking how it’s either sending roots further afield underground or is flowering (or will flower) to scatter its seed. Much of gardening isn’t about the here and now, so I also weed now for less weeds next season. It’s worth it.

Every time I look at a weed, I’m thinking how it’s either sending roots further afield underground or is flowering (or will flower) to scatter its seed. Much of gardening isn’t about the here and now, so I also weed now for less weeds next season. It’s worth it. After a few years of watching the weakened plant recover each season, I made cuttings from some of the stems. The cuttings rooted and the new plants, rather than being grafted, were then growing on their own roots. Even a cold winter wouldn’t kill the roots, living in soil where temperatures are moderated. If the stems died back to ground level, new sprouts would still sport those dark, red blossoms.

After a few years of watching the weakened plant recover each season, I made cuttings from some of the stems. The cuttings rooted and the new plants, rather than being grafted, were then growing on their own roots. Even a cold winter wouldn’t kill the roots, living in soil where temperatures are moderated. If the stems died back to ground level, new sprouts would still sport those dark, red blossoms.

Putting up the net always brings the words of fruit breeder Dr. Elwyn Meader to mind. When I visited him back in the 1980s, the old New Englander, still active in his retirement and growing about an acre of blueberries, among other crops, recounted in his slow, New Hampshire accent, “It takes a patient man to net an acre of blueberries.” Covering my two plantings encompassing a total of about a thousand square feet always creates a little tension.

Putting up the net always brings the words of fruit breeder Dr. Elwyn Meader to mind. When I visited him back in the 1980s, the old New Englander, still active in his retirement and growing about an acre of blueberries, among other crops, recounted in his slow, New Hampshire accent, “It takes a patient man to net an acre of blueberries.” Covering my two plantings encompassing a total of about a thousand square feet always creates a little tension. I now feel like a captain setting sail on an old sailing vessel, with all the sails trim and masts set. Except rather than sails and masts, it’s a blueberry net that’s spread tightly over the permanent, 7-foot-high perimeter of locust posts and side walls of anti-bird, plastic mesh. That netting covers 16 bushes within a 25 foot by 25 foot area. Rebar through holes near the tops of the locust posts keeps that side wall mesh taught and 18” high chicken wire along the bottom keeps rabbits, which love to teethe on that plastic mesh, from doing so.

I now feel like a captain setting sail on an old sailing vessel, with all the sails trim and masts set. Except rather than sails and masts, it’s a blueberry net that’s spread tightly over the permanent, 7-foot-high perimeter of locust posts and side walls of anti-bird, plastic mesh. That netting covers 16 bushes within a 25 foot by 25 foot area. Rebar through holes near the tops of the locust posts keeps that side wall mesh taught and 18” high chicken wire along the bottom keeps rabbits, which love to teethe on that plastic mesh, from doing so. Don’t worry about the birds. They get their fill of berries elsewhere. I don’t net my lowbush blueberries, nor my mulberries or gumis. Birds don’t usually share the mulberries or gumis with me. This year, for some reason, they are sharing.

Don’t worry about the birds. They get their fill of berries elsewhere. I don’t net my lowbush blueberries, nor my mulberries or gumis. Birds don’t usually share the mulberries or gumis with me. This year, for some reason, they are sharing. Juneberries are related to apples and pears, not blueberries, and share some of their kin’s pest problems. Especially in my garden. They’re one fruit that didn’t grow well for me so, years ago, I finally dug the plants up.

Juneberries are related to apples and pears, not blueberries, and share some of their kin’s pest problems. Especially in my garden. They’re one fruit that didn’t grow well for me so, years ago, I finally dug the plants up.

They’ve been making headway across the Northeast since arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1992. But my lilies still look fine and, yes, I do still see some of those beetles. Perhaps one of the natural predators released in Rhode Island years ago has joined the crowd here, minimizing damage.

They’ve been making headway across the Northeast since arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1992. But my lilies still look fine and, yes, I do still see some of those beetles. Perhaps one of the natural predators released in Rhode Island years ago has joined the crowd here, minimizing damage. Then, about 10 years later, and since then, they’ve showed up on schedule, which is now, but then disappeared for the rest of the season. Did they go off to greener pastures? Did they succumb to soil nematodes or fungi?

Then, about 10 years later, and since then, they’ve showed up on schedule, which is now, but then disappeared for the rest of the season. Did they go off to greener pastures? Did they succumb to soil nematodes or fungi? Although chemical, mechanical, and biological controls are still under development, this pest has not put an end to my blueberry-eating days. Thanks to some bait and kill traps developed by Cornell’s Peter Jentsch, damage has been kept to a minimum.

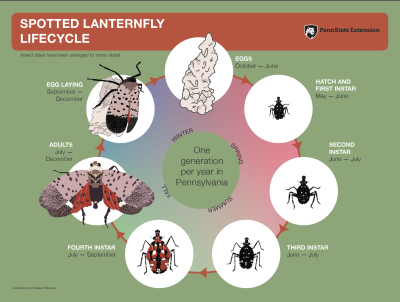

Although chemical, mechanical, and biological controls are still under development, this pest has not put an end to my blueberry-eating days. Thanks to some bait and kill traps developed by Cornell’s Peter Jentsch, damage has been kept to a minimum. To make matters worse, it also exudes a sticky honeydew which falls on any nearby surface (other leaves, lawn furniture, etc.) and, worse yet, becomes food for a fungus than turns that stickiness dark.

To make matters worse, it also exudes a sticky honeydew which falls on any nearby surface (other leaves, lawn furniture, etc.) and, worse yet, becomes food for a fungus than turns that stickiness dark. In spring, nymphs hatch and climb trees in search of soft, new growth. The one-inch long adults emerge around now; they’re very mobile, usually jumping but also capable of flying, which is when their spread wings display their bright red color. With wings folded, the insects are mostly gray wings with dark spots.

In spring, nymphs hatch and climb trees in search of soft, new growth. The one-inch long adults emerge around now; they’re very mobile, usually jumping but also capable of flying, which is when their spread wings display their bright red color. With wings folded, the insects are mostly gray wings with dark spots. A few natural predators, such as spiders and praying mantises, feast on SLF, but not enough. What to do? There are a few approaches.

A few natural predators, such as spiders and praying mantises, feast on SLF, but not enough. What to do? There are a few approaches. This ancient variety, elongated and with a black skin, has been grown almost exclusively near the Pardailhan region of France. Why am I growing it? The flavor is allegedly sweeter than most turnips, reminiscent of hazelnut or chestnut.

This ancient variety, elongated and with a black skin, has been grown almost exclusively near the Pardailhan region of France. Why am I growing it? The flavor is allegedly sweeter than most turnips, reminiscent of hazelnut or chestnut. Next year I can expect a vine growing 6 to 9 feet high and which is both decorative and tolerates some shade. What’s not to like? (I’ll report back with the flavor.)

Next year I can expect a vine growing 6 to 9 feet high and which is both decorative and tolerates some shade. What’s not to like? (I’ll report back with the flavor.) Later in the season, cluster of bulbs form, similar to shallots, although forming larger bulbs. They can overwinter and make new onion greens and bulbs the following years.

Later in the season, cluster of bulbs form, similar to shallots, although forming larger bulbs. They can overwinter and make new onion greens and bulbs the following years.

The problem was separating the small tubers from soil and small stones. I have a plan this time around — more about this at harvest time.

The problem was separating the small tubers from soil and small stones. I have a plan this time around — more about this at harvest time.

The next bins weren’t bins but just carefully stacked layers of ingredients, mostly horse manure, hay, and garden and kitchen gleanings. And then there was my three-sided bin made of slabwood.

The next bins weren’t bins but just carefully stacked layers of ingredients, mostly horse manure, hay, and garden and kitchen gleanings. And then there was my three-sided bin made of slabwood.

Which brings me to my current bin which, now, after many years of use, I consider nearly perfect. Instead of hemlock boards, these bins are made from “composite lumber.” Manufactured mostly from recycled materials, such as scrap wood, sawdust, and old plastic bags, composite lumber is used for decking so should last a long, long time.

Which brings me to my current bin which, now, after many years of use, I consider nearly perfect. Instead of hemlock boards, these bins are made from “composite lumber.” Manufactured mostly from recycled materials, such as scrap wood, sawdust, and old plastic bags, composite lumber is used for decking so should last a long, long time. When finished, I ripped one board of the bin full length down its center to provide two bottom boards so that the bottom edges of all 4 sides of the bin would sit right against on the ground.

When finished, I ripped one board of the bin full length down its center to provide two bottom boards so that the bottom edges of all 4 sides of the bin would sit right against on the ground. Before setting up a bin, I lay 1/2” hardware cloth on the ground to help keep at bay rodents that might try to crawl in from below.

Before setting up a bin, I lay 1/2” hardware cloth on the ground to help keep at bay rodents that might try to crawl in from below. With the Lincoln-log style design, the bin need be only as high as the material within while the pile is being built, and then “unbuilt” gradually as I removed the finished compost.

With the Lincoln-log style design, the bin need be only as high as the material within while the pile is being built, and then “unbuilt” gradually as I removed the finished compost.