FINAL HARVESTS

Compressed Gardening Experience

People are so ready to sit at the feet of any long-time gardener to glean words of wisdom. I roll my eyes. Someone who has gardened for ten, twenty, even more years might make the same mistakes every year for that number of years. I, for instance, swung a scythe wrong for 20 years; I may have it right now. Even a wizened gardener who has evaluated and corrected their mistakes has garnered experience only on their own plot of land; these experience may not apply to the differing soils, climates, and resources of other sites.

When I began gardening, my agricultural knowledge and experience was nil, zip, niets, rien, nada. But — and this is important — I had easy access to a whole university library devoted solely to agriculture. Hungry to learn, I read a lot. (I also was taking classes in agriculture.) In one year I was able to garner years of, if not actual experience, much of the knowledge that comes with that experience. And my garden showed it.

I’ve now gardened many decades and still gobble up the written word.

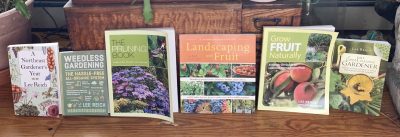

All of which is to say that reading reputable sources about gardening can make anyone a much better gardener and do so quicker than by gardening alone. “Reputable” is a key word in the previous sentence. So here’s the, to use the phrase of Magliozzi brothers on the radio show Cartalk, Shameless Commerce Division of this blog: a plug for my books. I stand firmly by anything I’ve written and am open to criticism.

Here’s the book list, all available from the usual sources or, signed, from me through this website (good gift idea, also):

•A Northeast Gardener’s Year: A month by month romp through all things garden-wise, what to do, how to do it, and when to do it.

•The Pruning Book: Plant responses, pruning tools, how to prune just about every plant (indoor, outdoor), and final sections on specialized pruning techniques, such as scything and espalier.

•Weedless Gardening: A four-part system, emulating Mother Nature and based on current agricultural research, that makes for less weeds and healthier plants, along with other benefits such as more efficient use of water and conservation of humus.

•Landscaping with Fruit: Following introductory chapters about designing your landscape is a listing of the best fruits to use for “luscious landscaping” in various regions and how to grow each of these fruiting trees, shrubs, vines, and groundcovers.

•Grow Fruit Naturally: Describes multi-faceted approaches to growing fruits without resorting to toxic sprays, starting with selecting kinds of fruits and varieties and moving on to encouraging natural predators, beefing up the soil, and more.

•The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden: Knowing some of the science behind what’s going on in the garden can make you an even better gardener; here’s how.

Vegetable Finale

And now, on to some gardening . . .

I’ve said it before and Yogi Berra said it before me, “It ain’t over till it’s over.” Last night’s temperature plummeting to 18°F was still not enough to put the brakes on the vegetable garden. Beneath their covered “tunnels,” arugula, mustard, endive, and napa Chinese cabbage still thrive. Along with mâche and kale, which aren’t under cover, all these greens are looking as perky as ever and, most important, taste better than ever.

Interestingly, temperatures I’ve measured within the tunnels are not that different — actually, not different at all — from temperatures I’ve measured outdoors. But something’s different. The increased humidity under the tunnels is probably at least partially responsible for the fresh tastes and appearances.

It’s a wonder that these tender, succulent leaves tolerate such temperatures. You’d think the liquid in their cells would freeze and burst the contents to smithereens. That would have been the case if the 18°F had come on suddenly, without any precedents.

Plants aren’t passive players in the garden. Increasingly cold weather and shortening days acclimated these plants to cold. (A month ago, temperatures dropped one night to 16°F.) Plants move water in and out of their cells, as needed, to avoid freezing injury. And increasing concentrations of dissolved minerals and sugars in the cells make the water freeze at lower temperatures. Perhaps that’s one reason why these vegetables taste so good. The tunnels also slow down swings in temperature, giving plants time to move water in and out of their cells and whatever else they do preparing for and recovering from cold.

Too many people, even gardeners(!), consider endive as nothing more than a bitter, green leaf best used as garnish. Reconsider. Given close spacing so that inner leaves of each head blanche from low light along with cool and cold temperatures, and endive takes on a wonderful, rich flavor.  Only the slightest hint of bitterness remains, enough to make the taste more lively — delicious in salads, soups, and sandwiches.

Only the slightest hint of bitterness remains, enough to make the taste more lively — delicious in salads, soups, and sandwiches.

Fruit Finale

The last fruits of the season, Szukis American persimmon, were harvested last week after over a month of eating them. Definitely the easiest fruit I grow. No pruning, no pest control. And definitely one of the tastiest: imagine a dried apricot soaked in water, dipped in honey, then given a dash of spice.

Fruits were very mushy for the final harvests — perfect for a jam. Squeezing a bunch of the fruits in a mesh bag (such as used for women’s “delicates” in a washing machine) pushed out  the pulp without seeds. No sweetener needed. Just jar it up and refrigerate (keeps about 2 weeks) or freeze. Delicious.

the pulp without seeds. No sweetener needed. Just jar it up and refrigerate (keeps about 2 weeks) or freeze. Delicious.