WEEDS, BIRDS, & PEST-FREE CURRANTS

I Battle Weeds and Birds, but Currants are Care-free

Part of my weedless gardening technique (which I thoroughly fleshed out in my book Weedless Gardening) involves — sad to say, for some people — weeding. After all, no garden can ever be truly weedless. Even people who spray Roundup eventually get weeds as they inadvertently “breed” for Roundup-resistant weeds, which now exist. My techniques are weed-less rather than weedless.

Which brings me to hoeing. Most years my hoe rests on its designated hook in the garage. This year, it’s hardly made it back to garage, mostly just leaning up against the garden fence alongside the gate. “And why is this?” you might ask. The answer is rain. This season, rainfall has been dropping in sufficient amounts at regular intervals, all of which has coaxed good plant growth, including that of weeds.

More importantly, the rainfall has promoted plant growth in paths and between widely spaced plants. One leg of my 4-legged “weedless gardening” stool calls for drip irrigation, which pinpoints water near plants. In a normal year, or a dry year, there’s little moisture to spur on weed growth elsewhere. This year, rainfall has democratically spurred weed growth everywhere.

Hence the hoe. The best hoes to snuff out young weeds without unduly disturbing the ground are ones with thin, sharp blades that lie parallel to the ground. All that’s needed is to slide such hoes back and forth a quarter of an inch or so beneath the surface, cutting the stems of hopeful, young interlopers. The work, if can be called that, is quick and easy, not calling for the “iron back with a hinge in it” recommended for a gardener by Charles Dudley Warner in his 19th century classic My Summer in the Garden. Too many people use a pull or draw hoe, whose blade lies perpendicular to the handle, to try to conquer weeds.

The hoes I’m recommending are so-called push or thrust hoes. Some examples include the collinear hoe, the scuffle hoe, the stirrup hoe, and, my favorite, the wingèd weeder. With any of these hoes, roots aren’t damaged and lower depths of soil remain at lower depths so that inevitable weeds seeds buried there are not awakened as they are exposed to light. (Minimal soil disturbance is another leg of my 4-legged “weedless gardening” stool.)

Still, my wingèd weeder is not effective unless it is used — frequently this season, ideally once a week or within a couple of days after a rain. Used in a timely manner, the wingèd weeder does a quick, effective, and satisfying job.

Currants are an Old-Fashioned Fruit Easy to Grow

“The currant takes the same place among fruits that the mule occupies among draught animals—being modest in its demands as to feed, shelter, and care, yet doing good service,” wrote a nineteenth-century horticulturalist. Hoeing takes time, especially this year, so it’s nice to balance that with something — currants, in this case — that is “modest in its demands.”

One of my currant bushes, a Perfection (that’s the variety name) red currant, splays its stems upward and outward in an ornamental bed in front of my house. Sharing that bed, for beauty and for good eating, are huckleberries, lowbush blueberries, and lingonberries, and, for beauty alone, mountain laurels and dwarf rhododendrons.

The only care my currant gets is, anytime from November until late March, pruning. The plant bears best on 2- and 3-year-old stems so I cut away anything older than 3 years old and reduce the number of new, 1-year-old stems to the half dozen or so most vigorous ones. The whole bed gets a sprinkling of either soybean meal (1# per hundred square feet) or alfalfa meal (3# per hundred square feet) in late fall, topped with a mulch of leaves or wood chips.

The only care my currant gets is, anytime from November until late March, pruning. The plant bears best on 2- and 3-year-old stems so I cut away anything older than 3 years old and reduce the number of new, 1-year-old stems to the half dozen or so most vigorous ones. The whole bed gets a sprinkling of either soybean meal (1# per hundred square feet) or alfalfa meal (3# per hundred square feet) in late fall, topped with a mulch of leaves or wood chips.

The bush began bearing towards the end of June and a few clusters of the plump, jewel-like fruits still hang from the branches. Most people use red currant for jelly or sauce. I like to eat them straight up, with my morning cereal, for instance. The flavor is tart early on but has mellowed by now.

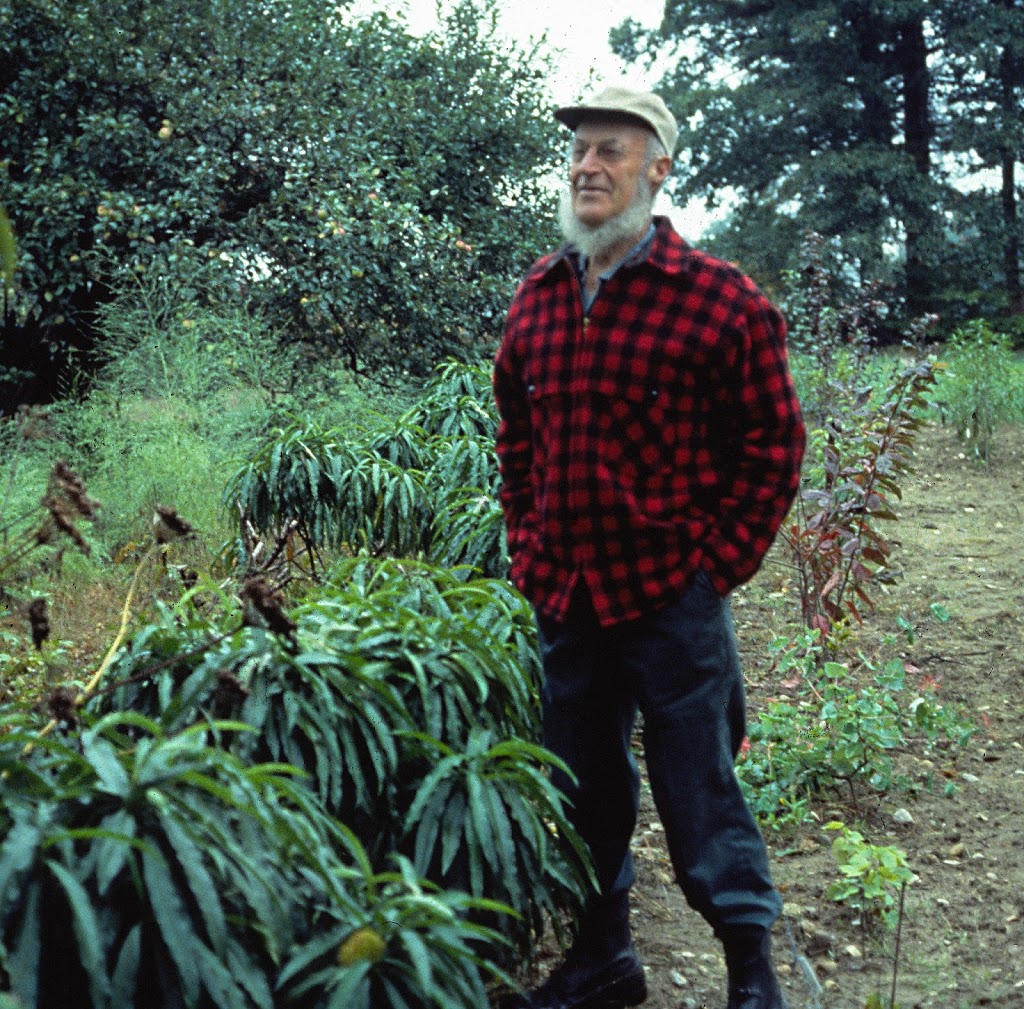

Currants were once a more popular fruit in America, and especially here in the Hudson Valley. They are one of the few fruits that tolerate shade (and deer!), and were often grown in the shade of large, old apple trees. Local folk, including children, would ride out to the orchards in hay wagons for communal picking.

Currant is, truly, among the uncommon fruits for every garden (good book title, that).

I Reluctantly Share Some Blueberries with Birds

Just a quick note about my blueberries, which are also relatively carefree. Last year’s abundance of cicadas may have upped bird populations, or at least made birds believe that lots of food would always be in the offing. Not so, birds. Perhaps, then, that’s why so many bird are fluttering all around my blueberries, mostly on the outside of the net that encloses my Blueberry Temple of 16 plants.

Right now a hawk — a cardboard one, swooping in breezes as it hangs from a string fixed to the end of an long, inclined bamboo pole — is meant to dissuade birds from even approaching the net. Calm mornings keep the hawk still enough so an occasional bird find their way through the net (where?) to venture into the Temple.