Invaders

Dare I Speak the Name?

As I was bicycling down the rail trail that runs past my back yard, I was almost bowled over by a most delectable aroma wafting from a most despised plants.  The plants were autumn olives (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrubs whose fine qualities I’m reluctant to mention for fear of eliciting scorn from you knowledgable readers.

The plants were autumn olives (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrubs whose fine qualities I’m reluctant to mention for fear of eliciting scorn from you knowledgable readers.

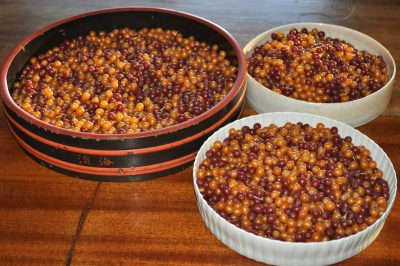

Yet, you’ve got to admit that the plant does have its assets, in addition to the sweet perfume of its flowers. Okay, here goes: The plant is decorative, with silvery leaves that are almost white on their undersides. And the masses of small fruits dress up the stems as they turn silver-flecked red (yellow, in some varieties) in late summer.  Those fruits are very puckery until a little after they turn red, but then become quite delicious, and healthful.

Those fruits are very puckery until a little after they turn red, but then become quite delicious, and healthful.

(I included autumn olive in my book Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden, and also planted them — but that was before the plant became illegal here.)

Another asset of autumn olive is that it actually improves the soil, converting air-borne nitrogen, which plants can’t use, into soil-borne nitrogen for use by autumn olives and nearby plants.

This native of Asia, introduced into the U.S. almost 200 years ago, was promoted in the last century as a plant for wildlife and soil improvement. Decades ago I worked for the USDA in what was then known as the Soil Conservation Service (now the Natural Resource Conservation Service), an agency that not only promoted the plant but also developed varieties for extensive planting.

Autumn olive likes it here and has invaded fields throughout the northeast, the Pacific northwest, and even Hawaii. It’s an invasive plant. Don’t grow it! (But feel free to enjoy its aroma, its beauty, and its fruits.)

One of My Favorite “Invasives”

As autumn olive blossoms fade, the temporary vacuum in sweet-perfumed air will be filled by another plant, black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia). That aroma comes from the white blossoms that dangle in chains like wisteria blooms from this tree’s branches.

Like autumn olive, black locust has other assets in addition to those offered by its blossoms. It’s a leguminous plant, like peas and beans, so, with the help of bacteria residing in its roots, also puts air-borne nitrogen into a form utilizable by plants.

Black locust’s other assets refer to it when dead: The dense wood is very resistant to rot — much, much more so than cedar — and is very high in BTUs for burning. I converted all my garden’s fenceposts and arbors, which I had previously made from cedar and lasted only about 10 years, to locust.

I’m lucky enough to have a mini-forest of them growing along one edge of my property. I cut them when they are five or six inches in diameter, and in 10 or so years I have a new one to replace the cut one. It adds up.

Quick growth and the ability to resprout from stumps and grow in poor soil by “making” its own nitrogen makes black locust, like autumn olive, a plant not loved by everyone. Despite being native here in the U.S., black locust has been classified as a “native invasive.” The reason is that it was originally native to only two regions in the U.S., from which it has now spread far and wide.

Change Will Come

The classification of “native invasive” highlights the capricious legality and classification of invasive plants. Where is the boundary within which a plant becomes an accepted native? In the mountain that rises up just behind my valley setting, lowbush and highbush blueberry are thriving natives. But these plants would never turn up here on my land, except that I planted them. (And both thrive.)

Clove currant is another plant I grow, one that, in addition to bearing spicy fruits, is resistant to just about every threat Nature could throw at it: deer, insects diseases, cold, drought. And it’s a native plant, but native throughout the midwest, not here. Should I call it a “native?”

Black locust is such a useful tree that its spread was aided and abetted by humans. But it also would have spread, albeit more slowly, without our intervention. Even autumn olive, given enough time, might have hitch-hiked here in some way from Asia.

The Earth’s landscape is not static. Changes represent interactions of climate, vectors, chance, and time. Nostalgia may have us wishing for the view out the window to remain the same as it was when we were children, but that’s not Mother Nature’s way.