WINTER ‘SHROOMS, SUMMER DREAMS, & A WINNER

Mushrooms Think It’s Autumn Again

The 15 oak logs sitting in the shade of my giant Norway spruce tree more than earned their keep last year. Seven of them got inoculated with plugs of shiitake mushroom spawn in the spring of 2013; eight of the were inoculated in the spring of 2014. With little further effort on my part, reasonably good flushes of mushrooms appeared through spring and summer, then heavy flushes through fall until the mild weather turned frosty.

My friends Bill and Lisa, also shiitake growers, told me a few days ago how they’re still harvesting good crops, cold weather notwithstanding. They brought one of their logs indoors, where it stands in the sink of their laundry room. Great idea!

I don’t have a laundry room, but I do have a cool, dark, moist basement, i.e. mushroom heaven. So a few days ago I carried one of my logs down the narrow basement stairway and propped it against the wall in a dark corner near the sump pit. That nearby pit could catch excess water in case the log needed to be watered.

No watering was needed: A few days after taking up residence in the basement, fat, juicy shiitake mushrooms exploded from the plugs up and down the log — so many that we had enough to dry for future use.

I’ll leave the log down there to see if it flushes again. If nothing happens within a few weeks, I’ll carry it back under the spruce and replace it with another log from outside. The few weeks in the cool basement might be enough time for more mycelial growth in the log in preparation for another flush. And then, sitting for some time in cold weather beneath the spruce might be just what a shiitake log needs to shock it into another cycle of production.

Rotating the logs between the basement and beneath the spruce could keep us in fresh mushrooms all winter long.

Winter Green

Most years, by this time, piles of snow would make it difficult for me to get to those outdoor shiitake logs. Recent weather, and predictions for the coming months, makes me wonder if I should even keep using the word “winter.”

I’d sacrifice fresh shiitakes for a real winter with plenty of snow. (We have enough quart jars of dried shiitakes to last well into warm weather.) It’s nice to have that white stuff to ski on. Snow even fertilizes the ground (“poor man’s manure”) as well as insulates it against cold.

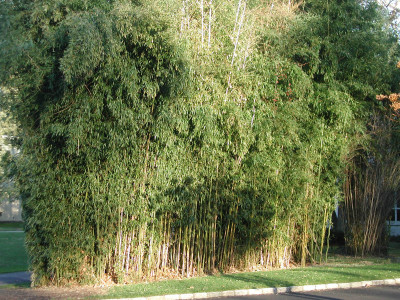

On the other hand, a mild winter has its appeal. Most winters, leaves and canes my yellow groove bamboo (Phyllostachys aureosulcata) are damaged — or, like last winter — killed back to the ground. The roots survive to re-sprout but the leaves turn brown and the new canes in spring are spindly. Some winters, like this winter probably, make for attractive (and useful) tall, thick canes dressed all winter long in green leaves.

Chester blackberry is another borderline hardy plant. It’s the hardiest of the thornless blackberries yet comes through most winter with many stems dried and browned — dead, that is. In the spring after our mild winters, stems are still green, foreshadowing a good crop of blackberries in late summer.

I’ve been waiting for a string of reliably milder winters to plant out my hardy orange plant (Citrus trifoliata). Yes, a citrus whose stems can just about survive to flower and fruit outdoors here, where winter temperatures normally plummet to minus 20°F or below. The fruit, sad to say, is only marginally palatable.

One more plus for a mild winter is the color green. The green of plants comes from chlorophyll, which is always decomposing, so must be continuously synthesized if the plant is to remain green. Synthesis requires warmth and sunlight, both at a premium during winters here. So most winters turn lawns muddy green or brown; even the green of evergreens, such as arborvitae, turn chalky green.

But not this winter — so far. Grass is still vibrant green, as are the arborvitaes and other evergreens.

My Favorites

My friend Sara asked me if I had yet ordered my seeds, and if I was getting anything especially interesting. Yes and hmmm.

As far as hmmm . . . I’ve tried a lot of very interesting plants over the years, too many of which — celtuce, garden huckleberry, vine peach, and white tomatoes, for example — were duds. So mostly, I restrain myself, devoting garden real estate to what I know either tastes or looks good, and grows well here in zone 5 or, more specifically, on my farmden. Some of my favorites include Shirofumi edamame, Blue Lake beans, Blacktail Mountain watermelon, Hakurei turnip, Sweet Italia and Italian Pepperoncini peppers, Golden Bantam sweet corn, Pennsylvania Dutch Butter Flavored and Pink Pearl popcorn, Lemon Gem marigold, and Shirley poppy.

I’m very finicky about what tomato varieties I plant, so won’t even mention them. Oh yes I will: Sungold, San Marzano, Paul Robeson, Brandywine, Belgian Giant, Amish Paste, Anna Russian, Valencia, Carmello, Cherokee Purple, and Nepal, to name a few.

And the Winner Is (drum roll) . . .

Thanks for all your comments, requested on last week’s post, about your soil care. Looks like you readers (or, at least, those of you who commented) are very savvy gardeners, enriching your soils with lots of organic materials. I chose one comment randomly fro the lot, the writer of which gets a free copy of my book Grow Fruit Naturally. Congratulations Selena.

For those of you who subscribe — or have attempted to subscribe to my weekly blog, a glitch is preventing you from getting email notifications. I just found out that the glitch has been glitching since back in September. I hope to get it fixed soon. Any suggestions? (The blog is in WordPress and subscriptions are with Feedburner, whatever that means). Stay tuned. If you want to just go to my blog site, new posts come out towards the end of every week.