Winter Games

Trying to identify leafless trees this time of year is a nice game I like to play alone or with a companion as we walk about enjoying the brisk winter air. I like this game because it forces me to take a close look at the more subtle details of plants, in so doing giving increasing appreciation of the plants even now when they are stripped of leaves and flowers.

Of course, this is hardly a game with some trees. Everyone recognizes paper birch by its peeling, white bark.  (Watch out, though, grey birch has similar bark.) Catalpa tree is quickly identified by its long, brown pods. And pin oak by its growth habit, its lower branches drooping downward, its mid-level branches spreading out horizontally, and its upper branches reaching for the sky.

(Watch out, though, grey birch has similar bark.) Catalpa tree is quickly identified by its long, brown pods. And pin oak by its growth habit, its lower branches drooping downward, its mid-level branches spreading out horizontally, and its upper branches reaching for the sky.

Most deciduous trees don’t have such obvious signatures this time of year. Then, what’s needed is an observant eye and a good resource to describe trees in words and pictures. Particularly helpful are those books that take you through a logical sequence of steps in identification. Fruit Key & Twig Key to Trees and Shrubs, by William Harlow is one such reference. Or the web, of course.

Buds, Twigs, and Fruit

One of the first features I look for when I’m confronted with an unknown, leafless tree is the arrangement of the buds on the young twigs. Are the buds “opposite” (in pairs, one bud right across another along each twig), or “alternate” (single and separated from each other along the length of stem)?

It turns out that most deciduous trees around here have alternate buds. Conversely, most shrubs have opposite buds. So if I see opposite buds on a tree, the choice immediately is narrowed to MADCapHorse. No, that’s not a typo; it’s an acronym for Maple, Ash, Dogwood, Caprifoliacae (honeysuckles and viburnums, for example), and Horsechestnut, all trees with opposite buds and leaves. That still leaves the challenge of honing down the choices of species within one of those genera or family groupings.

Other features further narrow the choices within opposite- or alternate-leaved trees. The shape of the buds can be telling. For example, flowering dogwoods have flower buds that look like little buttons capping short stalks.  Pawpaw’s buds are rusty brown, and fuzzy like velour. Also telling are twig color.

Pawpaw’s buds are rusty brown, and fuzzy like velour. Also telling are twig color.  Purple twigs covered with a cloudy coating identify a tree as boxelder.

Purple twigs covered with a cloudy coating identify a tree as boxelder.

Another feature I look for, hopefully before it finds me, is thorns. If present, the tree is most likely black locust, honeylocust (watch out again, though, because most cultivated forms of honeylocust are thornless), hawthorn, or wild plum. Black locust has short thorns, honeylocust has long thorns, often branching, and plum’s thorns are, in fact, short, sharp branches with little buds along their length. Not native here in the Hudson Valley, but occasionally planted — by me, for example — is osage orange, with the most vicious thorns of all.

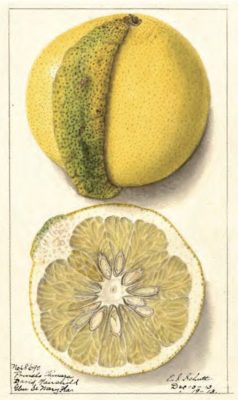

Fruits are another guide. Prickly gumballs hang almost through winter from sweetgum trees.

Magnolias still have their fruits, which look like little pineapples with red seeds popping out. And it’s within the rules of the game to look on the ground for help in naming a tree. There, you’ll still find some nuts of the shagbark hickory, identified also by its shaggy bark, and oak acorns. Then the game gets interesting, as I try to narrow down which of the 400 species (200 native to North America) dropped that acorn. Here’s an excellent website to hold my hand along this path. Knowing most of the native and frequently planted species lets me narrow those choices from the get go.

No obvious fruits or thorns, so still at a loss for a tree’s identity? The taste of a twig sometimes is the giveaway. Black cherry tastes like bitter almond, and yellow and river birch taste like wintergreen. Paper birch twigs are tasteless. Slippery elm twigs become mucilaginous when chewed.

My Favorite (Dog-free) Bark

My favorite winter tree feature, for identification and for beauty, is bark. And some are as obvious as paper birch. Shagbark hickory is as easy to pick out from a forest of trees as is paper birch.

Many others are similarly obvious. American hornbeam has smooth, blue-grey bark with ripples like muscle, which gives the tree one of its common names, muscle wood. Flowering dogwood’s bark is made up of small, squarish blocks. American persimmon has similar looking bark, except the blocks are larger and more raised, resembling alligator skin (but not frightening).

Flowering dogwood’s bark is made up of small, squarish blocks. American persimmon has similar looking bark, except the blocks are larger and more raised, resembling alligator skin (but not frightening).  Continuing in the zoological vein is beech, whose smooth, brawny trunk and limbs look like they could belong to a mythological elephant.

Continuing in the zoological vein is beech, whose smooth, brawny trunk and limbs look like they could belong to a mythological elephant.

Many maple species can be honed down by their distinctive bark. A bark that makes the trunk look like it’s been wrapped in buffed copper that curls away in fine curls is just like hanging a sign on the plant that says “paperbark maple.”  Sugar maple bark has grayish, vertical strips that, with age, becomes more furrowed and the strips start to detach. Large limbs attach to the trunk with distinctive furls.

Sugar maple bark has grayish, vertical strips that, with age, becomes more furrowed and the strips start to detach. Large limbs attach to the trunk with distinctive furls.

My favorite of all tree barks belongs to hackberry. I planted a couple of these trees just so I could enjoy their bark in winter. The smooth background of the gray bark is broken up by corky warts and ridges that play with shadow and light in a way that evokes the crisp, achromatic photographs of craters on the lunar landscape.

All this only scratches the surface of details that we tend to overlook in spring, summer, and fall. Some of these details are interesting, some have a subtle beauty, and some are useful only for identification.

As far as the identification game, there is one more very useful identifier. Deciduous trees are supposed to be leafless now. It’s not cheating to cast your eyes down for a leaf that may have dropped from the tree in question. A few leaves may even hang on into winter. They will be dead, dry, and twisted, but often still “readable.”

Not only that, but oaks and beeches are so reluctant to lose their lower leaves that you can spot these species even at some distance by their skirt of retained, dry leaves.

(An additional hardcopy resource for tree identification is the The Sibley Field Guide to Trees by David Allen Sibley.)

I could of course be careful to avoid leaf spotting by not spilling any water, especially cold water, on the leaves. Watering from below would do the trick, with periodic leaching from above to prevent buildup of salts. They also like high humidity.

I could of course be careful to avoid leaf spotting by not spilling any water, especially cold water, on the leaves. Watering from below would do the trick, with periodic leaching from above to prevent buildup of salts. They also like high humidity.

(Watch out, though, grey birch has similar bark.) Catalpa tree is quickly identified by its long, brown pods. And pin oak by its growth habit, its lower branches drooping downward, its mid-level branches spreading out horizontally, and its upper branches reaching for the sky.

(Watch out, though, grey birch has similar bark.) Catalpa tree is quickly identified by its long, brown pods. And pin oak by its growth habit, its lower branches drooping downward, its mid-level branches spreading out horizontally, and its upper branches reaching for the sky.

Pawpaw’s buds are rusty brown, and fuzzy like velour. Also telling are twig color.

Pawpaw’s buds are rusty brown, and fuzzy like velour. Also telling are twig color.  Purple twigs covered with a cloudy coating identify a tree as boxelder.

Purple twigs covered with a cloudy coating identify a tree as boxelder.

Flowering dogwood’s bark is made up of small, squarish blocks. American persimmon has similar looking bark, except the blocks are larger and more raised, resembling alligator skin (but not frightening).

Flowering dogwood’s bark is made up of small, squarish blocks. American persimmon has similar looking bark, except the blocks are larger and more raised, resembling alligator skin (but not frightening).  Continuing in the zoological vein is beech, whose smooth, brawny trunk and limbs look like they could belong to a mythological elephant.

Continuing in the zoological vein is beech, whose smooth, brawny trunk and limbs look like they could belong to a mythological elephant. Sugar maple bark has grayish, vertical strips that, with age, becomes more furrowed and the strips start to detach. Large limbs attach to the trunk with distinctive furls.

Sugar maple bark has grayish, vertical strips that, with age, becomes more furrowed and the strips start to detach. Large limbs attach to the trunk with distinctive furls.