ART, HISTORY, AND QUAINT NAMES

The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture Supporting Artists?!

I’ve been thumbing through my latest book, Fruit: From the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection. Most of the book is illustrations of many kinds and varieties of fruits painted by 20 artists over the years from 1892 to 1946. Most obvious is the beauty of the paintings. Less obvious is what they tell of fruit growing and marketing in this country.

For instance, why were the watercolors commissioned — by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, no less? To answer that question let’s first backtrack to before the middle of the 19th century. Up until then, fruit trees were planted mostly for cider, brandy, or to feed pigs. Fermented beverages were a more healthful drink than water at the time. (Just imagine all the tipsy kids wandering around!)

But then, around the middle of the 19th century, Americans began to take more pride in their fruits, not only the varieties carried here from foreign lands and the chance seedlings that were good enough to get a name, but also some of the native fruits. That passion was evident in the words of Louis Berckmans, famous horticulturalist of the nineteenth century, who wrote in 1857: “Let us now have our native varieties of all kinds of fruit. Already the pear, the strawberry, the raspberry, and chiefly the apple, have come in handsome competition with, or superseded, their European relative varieties. We never could see, after those successful experiments, what could prevent us from having just as fine gooseberries, grapes, etc, and better, too, than the transatlantic products. Gentlemen amateurs! do try all kinds of seedlings; the Phoenix is yet in its ‘ashes.’ Patience alone and ‘eternal vigilance’ can only bring out the desired results.”

Nurserymen (yes, they were mostly men) increasingly began to offer and promote varieties of fruits for eating—by humans! — rather than just random seedlings which usually bore fruit more fit for fermenting or feeding to animals. Jonathan Chapman, aka Johnny Appleseed, is the best known of those who planted seedlings. Named varieties — which need to be propagated by grafting because they don’t come “true” from seed — needed to be identified correctly.

The US government stepped in to help, with Congress establishing in 1886 the Division of Pomology (fruit growing) and initiating the Program of Pomological Watercolors, the work of which was created and shared for both promotional and educational purposes.

Storied Apples

Stories accompany many of the varieties. With all the seedlings planted, chance ones did occasionally bear very good tasting fruit. (Dr. Roger Way, apple breeder at Cornell University, once told me that the odds were only one in 10,000 for a seedling tree to bear fruit at least as good as the fruit from which the seed came.)

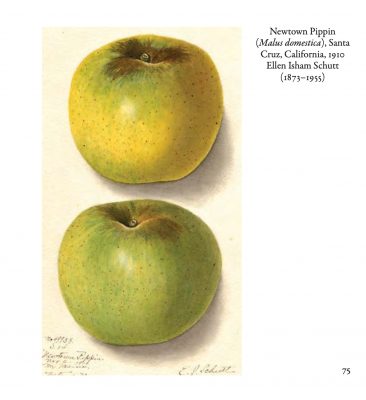

Nonetheless, perhaps reflecting all those seedlings Johnny Appleseed and others spread, not to mention self-sown seedlings, some did bear noteworthy fruits. Like the seedling that sprouted on a farm of Gershom Moore over 300 years ago. Gershom’s farm was in Newtown, New York, renamed Elmhurst, meaning “a grove of trees,” in 1897, a part of Queens. The Newtown Pippin became one of colonial America’s most famous apples, its popularity traveling south to the mid-Atlantic region, where it was called Albermarle Pippin. This apple was so popular that when Benjamin Franklin had Newtown Pippins shipped to him in England, it also became popular there. Decades later Queen Victoria was so “delighted with the perfect flavor and excellence of the fruit” that she removed her import tax for this variety.

As you can see from the watercolor, Newtown Pippin is not an apple for today’s market. And eye appeal is not all that’s lacking. When picked at the right moment, the fruit is hard and somewhat starchy. The way to experience the fruit at its best is to store it until February, or later, at which point the flavor is supreme. (I write from personal experience.)

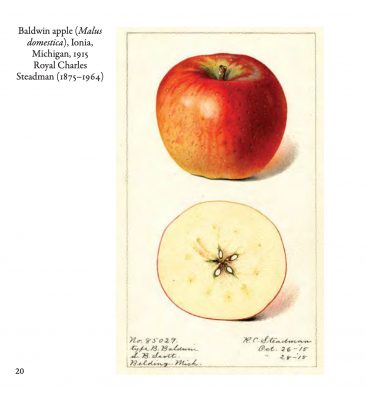

Baldwin apple, another variety originating as a chance seedling on American shores, was once one of the most widely planted varieties in the northeast.  There were thirty-four watercolors of this variety painted before 1934; then, abruptly, no further illustrations of this variety appear. Why? The winter of 1934 achieved fame for its severity, too severe for this widely planted apple variety. The death of two-thirds of the Baldwin trees put a quick end to this variety’s commercial popularity.

There were thirty-four watercolors of this variety painted before 1934; then, abruptly, no further illustrations of this variety appear. Why? The winter of 1934 achieved fame for its severity, too severe for this widely planted apple variety. The death of two-thirds of the Baldwin trees put a quick end to this variety’s commercial popularity.

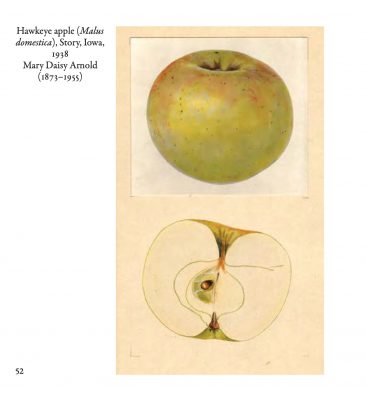

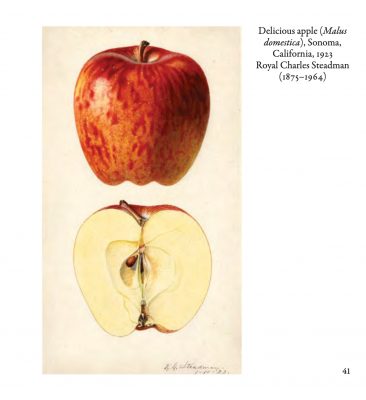

Turning next to the still widely grown, although infamous, variety Red Delicious. This variety began life as a seedling tree on the farm of Jesse Hiatt of Peru, Iowa, first fruiting in the 1870s. He named this deliciously sweet, blushed, almost yellow apple Hawkeye. It truly warranted the name “delicious.”  Jesse entered the fruit into a contest sponsored by Stark Brothers nursery. He won, and sold the rights to propagate the tree to the Stark Brothers Nursery, who renamed it Starking Delicious.

Jesse entered the fruit into a contest sponsored by Stark Brothers nursery. He won, and sold the rights to propagate the tree to the Stark Brothers Nursery, who renamed it Starking Delicious.

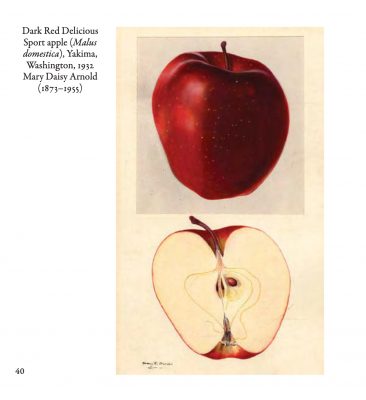

So why the infamy? Red Delicious became a victim of its own success. You’ll note that the watercolor of Hawkeye bears little resemblance to today’s Red Delicious in color or shape. Red Delicious tends to “sport”; that is, a bud may mutate slightly to become a branch bearing fruits slightly different from the rest of the tree. Over time, growers sought Red Delicious sports whose fruits were more and more elongated and, overall, a deep red color. This is evident if you compare the illustrations labeled Hawkeye, Red Delicious, and Red Delicious Sport.

Red Delicious in 1923

Red Delicious sport

Years ago, I ordered and received stems of Hawkeye which I grafted onto an apple rootstock. A few years later the tree bore fruit and, yes, it was truly delicious. Mine had more yellow and red on the skin.

Over the years, dozens of Red Delicious sports have been identified and patented, even ones that turne thoroughly red before they were ripe. No matter. Flavor was sacrificed for appearance, but by the middle of the twentieth century, apples were becoming more of a commodity, appealing to consumers’ eyes rather than their taste buds.

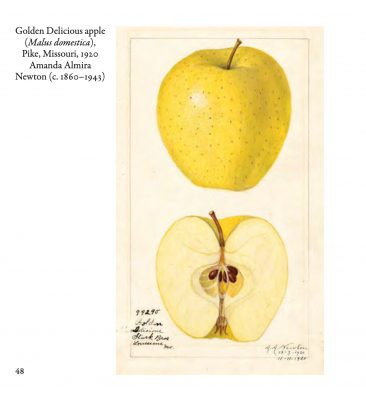

Golden Delicious, which I consider a very tasty apple if harvested fully ripe, was another seedling, this one from a seed that sprouted on the farm of Anderson Mullins in Clay County, West Virginia.  In 1914, Stark Brothers bought rights to this apple and also changed its local name from Mullin’s Yellow Seedling and Annit apple to Golden Delicious. Ba. To better differentiate this apple from their Starking Delicious, they renamed the latter Red Delicious.

In 1914, Stark Brothers bought rights to this apple and also changed its local name from Mullin’s Yellow Seedling and Annit apple to Golden Delicious. Ba. To better differentiate this apple from their Starking Delicious, they renamed the latter Red Delicious.

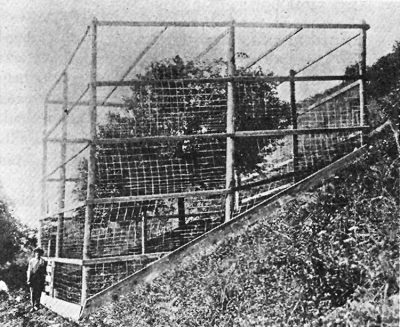

Original Delicious tree caged to protect from unauthorized propagation

What’s in a Name

Most of the 250 selections I made from the 7500 or so original watercolors were of apples, but many other fruits are also well represented in the originals and my selections for the book. Reflecting the especially great variability in shape, color, and flavor is the panoply of names apples were assigned.

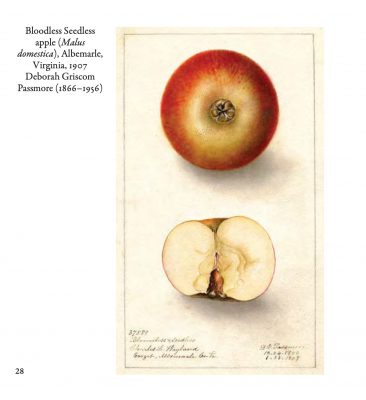

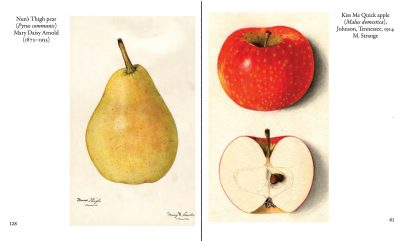

Many of the old varieties’ names have a quaintness, which I find appealing and usually lacking in modern varieties. Contrast the names of some of today’s newest apple varieties, such as Cosmic Crisp, SweeTango, Juici, Sonata, and RubyFrost, with names like Blushing Bride or Sops of Wine apple, or Neva Myss peach. (Speak the last one to get its meaning.) How well would a Red Democrat, Turn Off Lane, of Bloodless Seedless apple sell today? Or a Rambo? I would reach for a Peasgood Nonesuch or Peck’s Pleasant, a Seek No Further apple, or (dare I say it?) a Nun’s Thigh pear from a supermarket shelf. They may or may not have good flavor, but their intriguing names make them worth a bite.

Or a Rambo? I would reach for a Peasgood Nonesuch or Peck’s Pleasant, a Seek No Further apple, or (dare I say it?) a Nun’s Thigh pear from a supermarket shelf. They may or may not have good flavor, but their intriguing names make them worth a bite.

I think that Newtown Pippin looks great. Wonder if it is anything like the Gold Rush apple of today which ripens late and then needs to be stored for awhile to reach it flavor peak?

Definitely not anything like Goldrush. Many apples ripen late and need some storage for peak flavor. York, for instance, although even at its peak it’s not that great.

Newtown Pippins still exist. I pick them every fall at an orchard near Front Royal, VA. (They call them Ablemarle Pippins.) They are grown in other orchards as well – have heard of availability near Charlottesville, VA and other places including in New York state.

Yes, there are quite a few orchards these days that grow lots of varieties, and not just the new ones.