TWO DISAPPOINTING FAILURES, TWO DELICIOUS SUCCESSES

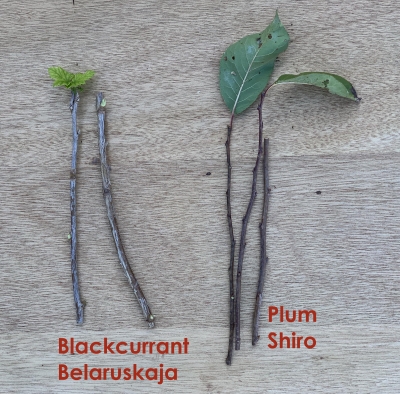

Help!!

As flaming red petals drop to the ground beneath my pomegranate bush, I’m not hopeful. Sure, the flowers are beautiful, but the plant is here to give me fruit.

To survive winters here in New York’s mid-Hudson Valley (Zone 5), my plant’s home is in a large flowerpot which I cart into cold storage in late December and back outdoors or into the greenhouse in late winter or early spring. Even my cold-hardy variety, Salatavski, from western Asia, would die to ground level if planted outdoors. The roots would survive that much cold because of moderated below ground temperatures, but new stems that would rise from ground level would need to be more than a year old before flowering.

Potted pomegranate, but NOT mine

Growing in a pot, my pomegranate (and other potted fruit plants) need regular pruning and repotting. To prune the pomegranate, I snip off young suckers growing from ground level, shorten lanky stems, and thin out stems where congested. I repot the plant every 2 or 3 years, cutting off roots and potting soil from around the root ball to make room for new potting soil.

When flowers do appear, which they do over the course of a few weeks, I dab their faces with an artists’ brush. Going from flower to flower spreads the pollen from male flowers to the female parts (stigmas) of the hermaphroditic flowers.

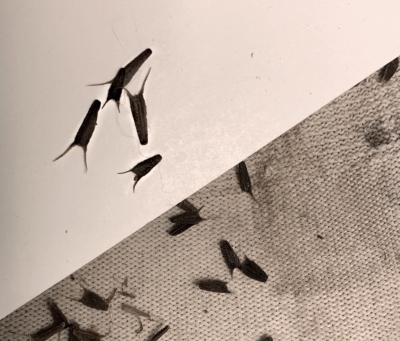

Male pomegranate flowers

Hermaphroditic pomegranate flower

Then I wait, my eyes concentrating on each flower and hoping to see the base swelling. Problem is most, some year all, the flowers open and then drop. Occasionally, in past years, a flower or two has swelled into a mini-pomegranate. Then also dropped.

Swelling pomegranate fruitlet

I’ve ministered to this plant for years and it has never rewarded me with a single fruit. Help! Any suggestions?

Not So Idle Threats

Every summer, as my pomegranate drops its last flowers, I’ve threatened it with the same fate I wrought upon another of my subtropical fruit plants, pineapple guava. Beneath the thin, green skin of this torpedo-shaped fruit lies a gelatinous center with a minty pineapple flavor.

Pollinating pineapple guava

Over the course of growing this fruit for many years, I did harvest a few, small fruits from this plant, but not enough to keep me from reincarnating it as compost. (The flowers, however, reliably produced, sport the most delicious, fleshy petals of any that I’ve taste, with a strong, sweet minty flavor.)

A Most Delicious Fruit

Not all has been failure with my growing subtropical fruits.

My most recent success has been with Pakistani mulberry, Morus macroura, native to Tibet, the Himalayas, and mountainous regions of Indochina. I first tasted this fruit a few years ago at a nursery in Washington State and was swept away by the delicious flavor, sweet with enough tartness to make it interesting, and a strong berry undertone. (Yes, mulberry does have “berry” in its name, but botanically, it’s not a berry; it’s a “multiple fruit.”)

Besides having great flavor, Pakistani fruit is also notable for its enormous size, each one elongating, when ripe, to between three and five inches!

Pakistani mulberry is easy to grow and needs no particular coaxing to bear plenty of fruit, which it does over the course of a few weeks. Mine grows in a pot measuring a little over a foot wide, with the tree rising about four feet high. Fruits are borne on new shoots that grow off older stems, which keeps the tree very manageable. Shortening those older stems each year makes it easier to muscle the plant through doorways to move it indoors for winter and then back outdoors when weather warms a little.

Very Easy, Very Successful, Very Delicious

My longest term and greatest success with subtropical plants has been, of course, with figs. (I write “of course” because I’ve written a whole book whose content is described by its title, Growing Figs in Cold Climates, and now is available as a video of a webinar I have presented on that topic.)

Like mulberries, to which they are related, figs — most varieties — can bear fruit on new shoots that grow off older branches.  So, like mulberry, the plants can be pruned back some so they’re more manageable to be protected from bitter winter cold. An in-ground plant, then, could be protected from bitter winter cold by being swaddled upright or lowered to the ground, even trained to grow along the ground; a potted plant is more easily maneuvered into a garage, unheated basement, or other cool location for its winter rest.

So, like mulberry, the plants can be pruned back some so they’re more manageable to be protected from bitter winter cold. An in-ground plant, then, could be protected from bitter winter cold by being swaddled upright or lowered to the ground, even trained to grow along the ground; a potted plant is more easily maneuvered into a garage, unheated basement, or other cool location for its winter rest.

Right now, there’s nothing for me to do with my figs except watch them grow. Small figlets now sit in the plants’ leaf nodes. They’ll just sit there, doing nothing, for a seemingly long time. Once ripening time draws near, the figs suddenly puff up, becoming soft and juicy and developing a honey sweet, rich flavor.

Last reminder for

Last reminder for

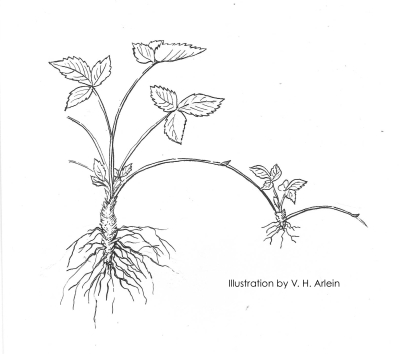

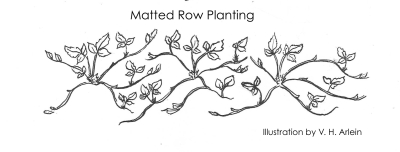

Eventually, plants in a strawberry bed should be 6 to 12 inches apart. The “matted row” system of strawberry planting makes full use of these runners. Plants are set far apart (4 feet between rows and 2 feet between plants) and the spaces between the plants fill in with runner plants which fruit the following season.

Eventually, plants in a strawberry bed should be 6 to 12 inches apart. The “matted row” system of strawberry planting makes full use of these runners. Plants are set far apart (4 feet between rows and 2 feet between plants) and the spaces between the plants fill in with runner plants which fruit the following season.  The matted row is allowed to fill in to a width of 2 feet, and all plants attempting to spread beyond that width are kept in bounds with a rototiller or by hand. With age, that 2 foot ribbon rapidly becomes overcrowded unless old plants are weeded out.

The matted row is allowed to fill in to a width of 2 feet, and all plants attempting to spread beyond that width are kept in bounds with a rototiller or by hand. With age, that 2 foot ribbon rapidly becomes overcrowded unless old plants are weeded out.

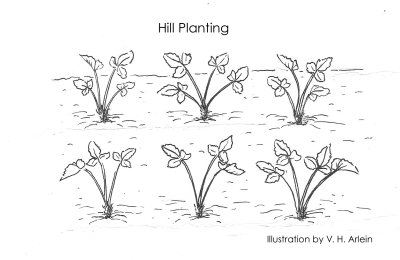

The hill system demands the somewhat tedious job of pinching off all runners through the summer, but the planting stays neater and yields the most berries the first bearing season.

The hill system demands the somewhat tedious job of pinching off all runners through the summer, but the planting stays neater and yields the most berries the first bearing season.

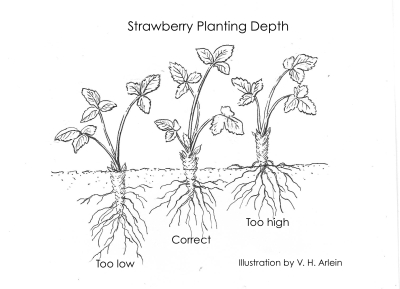

With the roots fanned out by my other hand, the trimmed plant’s roots fit easily into the waiting slit. Planting is completed as I remove the trowel and firm soil against the roots with the heel of my hand.

With the roots fanned out by my other hand, the trimmed plant’s roots fit easily into the waiting slit. Planting is completed as I remove the trowel and firm soil against the roots with the heel of my hand.

To the south my meadow ends at a sweep of another neighbor’s field, the more frequently mown grass of which undulate like waves in summer sunshine in contrast to the more upright asters, fleabanes, goldenrods, and monardas that stand upright among the grasses in my meadow.

To the south my meadow ends at a sweep of another neighbor’s field, the more frequently mown grass of which undulate like waves in summer sunshine in contrast to the more upright asters, fleabanes, goldenrods, and monardas that stand upright among the grasses in my meadow.

From an auspicious vantage point, a pear tree glowed like a subdued holiday tree as hints of sunlight’s reds and blues refracted from the natural prisms on the branches.

From an auspicious vantage point, a pear tree glowed like a subdued holiday tree as hints of sunlight’s reds and blues refracted from the natural prisms on the branches.

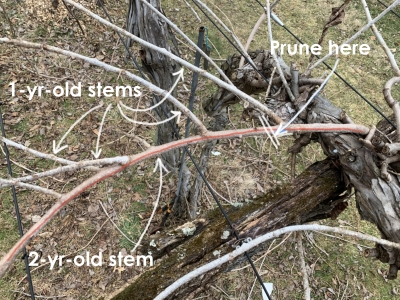

The goals in pruning are to keep the plant reined in to a convenient size for easy harvest, to eliminate enough stems so that those that remain bathe in sunlight and air, and to coax growth of new stems off which will emerge, the following year’s fruiting shoots.

The goals in pruning are to keep the plant reined in to a convenient size for easy harvest, to eliminate enough stems so that those that remain bathe in sunlight and air, and to coax growth of new stems off which will emerge, the following year’s fruiting shoots.

It’s that purple again, light purple in this case. Also, the plants weren’t exactly smothered with flowers and most prominent, then, were the leaves which were not particularly attractive.

It’s that purple again, light purple in this case. Also, the plants weren’t exactly smothered with flowers and most prominent, then, were the leaves which were not particularly attractive.

Those are Bidens, trying to spread. (Not to be confused with the round, marble-size burs of burdock.)

Those are Bidens, trying to spread. (Not to be confused with the round, marble-size burs of burdock.)

The bright red berries hang on the plants for a long time, well into winter, with their backdrop of holly-green, glossy leaves making a perfect holiday decoration in situ.

The bright red berries hang on the plants for a long time, well into winter, with their backdrop of holly-green, glossy leaves making a perfect holiday decoration in situ.