ONE OF THANKSGIVING’S UNSUNG HEROES

/15 Comments/in Gardening, Vegetables/by Lee ReichYears ago I wrote about one of the unsung heroes of Thanksgiving, the groundnut (Apios americanum). This plant, which helped nourish the Pilgrims through their first winters, never achieved the reknown of corn, pumpkins, cranberries, and other foods of the season.

When I first wrote about groundnuts, I had just planted them. I pointed out that there was renewed interest in the plant, though specifics as to how to grow it were wanting and selection of superior clones was just beginning. Now that I have grown groundnut for a few (thirty plus!) years, I am ready to share my experiences.

It Looks Like . . . And Acts Like . . .

As you might guess from the name, the plant makes edible tubers, usually the size of golfballs and strung together on a thinner, ropelike root. The swollen roots on one of my plants are more the size of tennis balls than golf balls. Not as obvious, below ground, at least, is that the plant is a legume; as such, it can “fix” atmospheric nitrogen, that is, put it in a plant-available form.

The plant also has shown some virtues aboveground. Chocolatey brown flowers dangle like jewelry from the twining stems. The flowers are pretty enough to have accorded groundnut a place in flower gardens in France a hundred years ago. On some plants, the flowers also have a strong and delicious aroma – vanilla, instead of chocolate, though.

I started some of my plants from seed; others I purchased growing in pots. I trained each vine up and down and around a tomato cage. The plants were and still are in full sun and rich soil, with a thick mulch of wood chips. The ground is so fluffy that I can harvest by just grabbing one end of a root, then pulling it up and out of the soil.

Soon after I planted groundnut, I discovered that it is weedy. I was soon finding plants, first sneaking across the ground a couple of feet from mother plants, and then further and further.

Aboveground, the twining stems reached around and insinuated themselves amongst the branches of a nearby bush cherries and other plants.

To further unsettle me, I was startled at the reappearance, with vigor, of one young plant which I thought I had destroyed as I dug looking for edible roots. (I since learned that harvest must be delayed until the second season.) I hope groundnut will not prove to be as unruly and as hard to remove as the horseradish I once foolishly planted in the garden!

Is It Good To Eat?

Now for the important question: What does groundnut taste like? Thomas Hariot, in A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia (1590) may have been the first to write of groundnut, and his opinion was “boiled or sodden they are very good meate.” In 1602, a correspondent from New England wrote to Sir Walter Raleigh that groundnuts were “as good as potatoes.”

Dr. E. Lewis Sturtevant (Sturtevant’s Notes on Edible Plants, 1919) reported an eighteenth century horticulturalist writing that the “Swedes ate them for want of bread, and that in 1749 some of the English ate them instead of potatoes.” He also quotes a nineteenth century writer, who wrote that the Pilgrims “were enforced to live on ground nuts.”

Moving up to the twentieth century, wild food forager Euell Gibbons, who enjoyed everything from cattails to milkweed pods, was reserved in his praise of groundnuts.

I have harvested groundnuts and, because they should not be consumed raw, boiled some and baked some. They taste almost as good as potatoes, though less distinctive. The texture was dry and mealy. Like Euell, I am reserved in my praise of the roots, though other groundnut plants might have better or worse roots. (After all, not all potatoes taste the same.)

I do think that groundnut, even in its present primitive state, is a native, perennial, permaculture friendly vegetable (I have been accused by some of being a permaculturalist) good enough to deserve a place at the Thanksgiving table. That is, it deserves a place in the garden and on the Thanksgiving table as long as it’s planted where its growth and spread can be reined in.

How about calling it one of its Indian names – nu nu, perhaps – and making nu nu stuffing standard Thanksgiving fare? Happy Thanksgiving!

GHOST OF A NOVEMBER PAST

/10 Comments/in Houseplants, Vegetables/by Lee ReichA Vine or a Bush?

Here’s a blast from the past, from my November 20, 2009 blog post, with current commentaries on how things have changed — and not changed — over the past 11 years.

Dateline: New Paltz, NY, November 20, 2009, 5:30 am. New models of plants, like cars, are deemed necessary to keep consumers interested and spending money. My cars (actually trucks . . . you know, manure and all that) stay with me for as long as they keep rolling along, so it was with equal skepticism I looked upon a new “model” of mandevilla, called Crimson, that arrived at my doorstep early last summer.

I was first attracted and introduced to mandevilla about 20 years ago. The glossy leaves and the bright red, funnel shaped flowers, were part of the attraction. The  vining habit was also a big part of the draw, making the plant a stand-in for morning glory, but with prettier leaves and brighter flowers. Mandevilla is a perennial, tropical vine, so must winter indoors rather than be seeded outdoors each spring like morning glory. My vine’s leaves yellowed so much in winter that I tired of looking at it; one winter day I walked it over to the compost pile.

vining habit was also a big part of the draw, making the plant a stand-in for morning glory, but with prettier leaves and brighter flowers. Mandevilla is a perennial, tropical vine, so must winter indoors rather than be seeded outdoors each spring like morning glory. My vine’s leaves yellowed so much in winter that I tired of looking at it; one winter day I walked it over to the compost pile.

The variety Crimson is a new kind of mandevilla whose main selling point is its bushy growth habit. So yes, it is different and new, but wasn’t that vining habit one of the things I always liked about mandevilla?

Still, I have grown very fond of Crimson. It flowered continuously all summer and, since coming indoors in September, continues to do so, with new buds on the way (at every third leaf bud, according to the “manufacturer.”) I’m going to think of Crimson mandevilla as a very pretty, long blooming, bushy plant. Yes, it’s a worthy new model.

Dateline: New Paltz, NY, November 19, 2020: Well, Crimson evidently was not that worthy; it’s no longer with me. As I remember, that sickly look that eventually came on in winter didn’t justify its tenancy here.

With that said, someday I may still grow mandevilla again. But not Crimson or any other bushy variety. As I wrote 11 years ago, that vining habit was one of its main attractions. If I do grow it again, I’ll put it in the basement or somewhere where I’ll hardly see it, for it to sit out winter.

Are They Really Sickly?

(2009) Sickly-looking leaves of houseplants – such as my mandevilla of yore – can be traced to a number of causes. Already I’m seeing this yellow transformation creeping up on my gardenia, which just finished one of its many fragrant shows.

Both mandevilla and gardenia need soils that are quite acidic (pH 4-5.5) in order to thrive. Not enough acidity makes it hard for the plant to imbibe iron, resulting in iron deficiency and yellow leaves.

But wait! It’s not time yet for the “iron pills.” Looking more closely at my gardenia, I see that it is the OLDEST leaves that are yellowing. Hunger for iron causes the YOUNGEST leaves to yellow (and for their veins to remain green). Yellowing of older leaves most commonly means that the plant isn’t getting enough nitrogen. The nitrogen is being robbed from older leaves (which turn yellow because nitrogen is an important component of green chlorophyll) to feed the younger leaves.

The prescription? Add some soluble nitrogen fertilizer and pay more attention to watering. Too much water drives air out of the soil, and roots gasping for air have trouble doing their work to take up sufficient nutrients.

(2020) I mostly agree with my past diagnosis of and cure for yellowing leaves. But two other considerations are worthy of attention.

First, temperatures in my home are on the cool side and roots are less functional as temperatures cool, especially the roots of warm climate plants. So roots might not be able to make efficient use of nitrogen even if it’s added to the soil.

And second, even evergreen plants go through periods of shedding their oldest leaves. Before these leaves drop, they lose their chlorophyll and turn yellow.

So under natural and under less than perfect conditions, mandevilla and gardenia are unavoidably going to look sickly in late fall and early winter.

Oh, the gardenia is also no longer a resident here. Too prone to scale insects.

Asparagus’ Leaves, Their Work Finished

(2009) Yellowing leaves are not always a bad thing. (Think of birch leaves a few weeks ago, or aspen leaves.) I’m happy that my asparagus’ leaves have yellowed. The plants have been growing vigorously all season, feeding their roots to fuel next year’s growth of the delicious young spears that I’ll be snapping off at ground level from late April to early July.

With this year’s work finished, the shoots and leaves, left to grow unfettered since early July, are yellowing and dying back. My short-bladed brush scythe was the perfect tool to make quick work of the plants, a fluffy addition to the compost pile.

With the asparagus shoots and leaves cleared away, I could get into that bed and weed it. The bed was pretty much weed-free until July, but then wet summer weather kept  weeds germinating and growing, and hard to reach among the 6-foot-high forest of feathery stalks. The bed is now weeded and soon to be fertilized (2#/100 square feet of soybean meal) and mulched (wood chips 2 inches deep).

weeds germinating and growing, and hard to reach among the 6-foot-high forest of feathery stalks. The bed is now weeded and soon to be fertilized (2#/100 square feet of soybean meal) and mulched (wood chips 2 inches deep).

(2020) Wow! Right on schedule, on the same date as 11 years ago, asparagus leaves have yellowed. They’ve pumped nutrients and fuel down to their roots to provide for next spring’s growth, and are no longer functional and could harbor pests. So, like 11 years ago, I’m going to cut them down and add them to the compost pile.

This year I did treat the ground differently from the past 11+ years. Right after this year’s harvest, at the end of June, when the whole bed was cut to the ground, I did a little weeding. And then, instead of soybean meal as a fertilizer, I spread an inch of compost. Compost adds organic matter to the soil, and supplies a wider slew of nutrients and is more sustainable than soybean meal, among other benefits. The compost would also smother some weeds that would try to emerge.

Then, just to further smother weeds, I topped the compost with a one inch layer of wood chips.

I’m proud to report that the asparagus bed has never been so weed-free. No doubt, the very dry summer weather also played a part in keeping weeds at bay.

At any rate, I’m getting out the scythe now to cut down the stalks. And I look forward to a good crop of asparagus beginning at the end of April. I highly recommend growing asparagus: it’s perennial and is one of those vegetable whose flavor is markedly different, and much, much better, when eaten fresh-picked.

FROM PAST TO PRESENT

/4 Comments/in Fruit/by Lee ReichBr-r-r-r-r-r

This post originally appeared November 7, 2009. Here’s an update with commentaries on how things have changed — and not changed — over the past 11 years.

Dateline: New Paltz, NY, October 19, 2009, 5:30 am. I bet my garden is colder than your garden. I was startled this morning to see the thermometer reading 23 degrees F. Not much I could do at that point about protecting “cold weather” vegetables still in the garden, some covered with floating row covers and some in “plein aire.” The thing to do under these circumstances was wait for the sun to slowly warm everything up and then assess the damage.

2009

I ventured out to the garden for a survey in the sunny midafternoon. Joy of joys. None of the cold-hardy vegetables was damaged by the cold. Romaine lettuces stood upright and crisp, arugula was dark green and tender, radishes were unfazed, and the bed of endive, escarole, and radicchio looked ready to face whatever cold the weeks ahead might offer.

That 23 degree temperature reading came from my digital thermometer, read indoors from a remote sensor out in the garden. Most surprising was the reading from the old-fashioned minimum/maximum registering mercury thermometer out in the garden. This thermometer remembered the night’s lowest temperature as 20 degrees F. Brrrrrrrr.

2020

Dateline: New Paltz, NY, November 11, 2020. This fall has likewise had a few frigid dips in the thermometer, down a couple of times to 24°F, and cold temperature vegetables have likewise fared well. Nowadays I check temperatures with a high-tech, but reasonably-priced, Sensorpush, a small sensor strategically hung in the garden. It beams current temperature and humidity back to my smartphone, and keeps a record of them throughout the day, week, month, and year. Its reporting jives with that of my “old-fashioned minimum/maximum registering mercury thermometer”.

What has changed is the weather over the past couple of weeks, with sunny days and temperatures hovering around 70°F. A fitting closing for a stellar year in the garden: best harvest, best fall color, congenial weather.

The effect of microclimate has been startling. I live about 4 miles out of town, on a road that follows the valley along the Wallkill River. On clear nights, radiation frosts spill cold air downhill to bring the temperature at the farmden about 5° colder than in town. A couple of evenings ago, temperature in town, as displayed on the local bank building and on my car thermometer as I drove through town, was 55°. Arriving at the farmden, the car thermometer, Sensorpush, and the “old-fashioned minimum/maximum registering mercury thermometer” registered 42° — quite a dramatic difference for a 40 foot elevation difference.

Mediterranean Fancies

(2009) Moving, figuratively, to warmer climes: the Mediterranean. I’m taking the Mediterranean diet one step further by trying to grow some of the delectable woody plants of that that region.

Figs are a big success, and not an unfamiliar sight well beyond their natural range. I’ve tried all the usual methods of growing them in cold climates. I’ve grown them in pots brought indoors for winter; I’ve bent over and covered or buried the stems to protect them from cold; I’ve swaddled the upright stems in leaves, straw, wood shavings, or other insulating materials. All yielded some fruit, but none of these methods beats having a small greenhouse with the trees planted right in the ground. Handfuls of soft figs, so ripe that each has a little tear in its “eye,” follow each sunny day and should do so for a few more weeks.

Bay (as in “bay leaf”) also does well, this one potted. After 20 years, my bay laurel is a

Bay laurel, 2009

handsome little tree, trained to a ball of leaves atop a single, four-foot trunk. The fresh leaves are much more flavorful, almost oily, than dried leaves, especially the old, dried leaves typically offered for sale.

(2020) Yes, figs have been abundant in the greenhouse over the past 11 years. But diminishing sunlight and cooler temperatures, even in the greenhouse (37° minimum temperature), have drained the flavor from the few ripe, remaining figs.

After 30 years, the bay is still thriving, valued as much for its beauty as for the flavor of its fresh leaves. It’s still trained as a small tree, smaller than in the past. I lopped the whole plant to the ground a few years ago to give it a fresh start, trained as round-headed tree only thirty inches tall.

Bay Laurel 2020

(2009) Three hopeful Mediterranean transplants are my olive, feijoa, and lemons. I purchased the olive tree in spring, whereupon it flowered and has actually set a single fruit! The feijoa, also known as pineapple guava, has two fruits on it, which might not seem like a big thing except that those two fruits represent the culmination of about 15 years of effort. (More on that some other time.) True, feijoa is native to South America, but it thrives and is often planted in Mediterranean climates. The same goes for lemon, except that it is native to Asia. My Meyer lemon hybrid, like the olive, was potted up this past spring and sports a single fruit.

The long shots among my Mediterreans are pomegranates. My two plants – the varieties Kazake and Salavastki – are cold-hardy, early ripening, sweet varieties from central Asia, so should do well here in a pot. (They are cold-hardy for pomegranates, down to a few degrees below zero degrees F.) They have yet to flower and fruit.

In a few weeks I’ll move all the potted fruits to the sunny window in my very cool basement, where winter weather is very Mediterranean-esque.

(2020) All three trees are still residents here, although the feijoa tenuously so. It’s a pretty plant but what I really want from it is fruit. Yields have been paltry. I’ve repeatedly threatened it with the compost pile, but repeatedly reneged. Besides its beauty, it often flowers, and the flower petals, fleshy, pinapple-y, and minty, are delicious.

One year, in an effort to downsize plant-wise, I was also going to walk the olive to the compost pile. And then someone reminded me that the olive is a symbol of peace, so I kept it. It’s a pretty plant, an easy to care for houseplant, and occasionally bears tasty olives.

The Meyer lemon offers so much everything: deliciously fragrant flowers, verdant leaves year ‘round, and tasty lemons. Just not enough of them. Meyer lemon is actually a hybrid of lemon and sweet orange.

Pomegranate is still a long shot. I’m down to one plant, Salavastki. It often flowers and sets a few fruits, but the fruits drop off. I’m still not sure why.

Still Great After All Those Years

2009

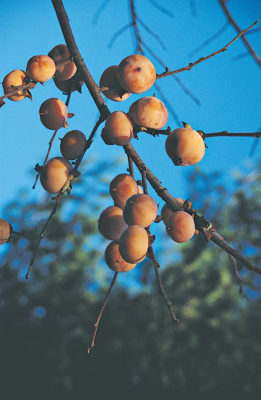

(2009) Persimmon is another tree grown in Mediterranean countries, although it’s not native there. Up here, I grow American persimmon, an outdoor tree that is cold hardy to below minus 20 degrees F.. Besides yielding delectable fruits, it’s a tree that requires almost no care, not even pruning. Some of the tree’s branches are deciduous, naturally dropping in autumn.

Heavy winds of a few weeks ago took the persimmon’s self-pruning theme too far and blew the top off my 20 year old tree. Fortunately, my three other persimmon trees remained unscathed. I’ll just trim the break from the decapitated tree and it will be fine.

2020

(2020) Persimmon is still thriving, still care-free, and still delectable, the ripe fruits tasting like dried apricots that have been soaked in water, dipped in honey, and given a dash of spice. My persimmon “herd” has been thinned to my two best-tasting, most reliable varieties: Szukis and Mohler. Both are well-adapted to ripening in the the relatively short season (for a persimmon) this far north. Right now, the leafless tree is leafless and still loaded with fruit for the picking, much more than I can eat.