THE SHOW GOES ON

/5 Comments/in Design, Planning/by Lee ReichLesser Known

A whole slew of clear, sunny days and cool nights caused sugar maples to put on a particularly fiery show of yellow and orange leaves this fall. That’s mostly over now around here — but a number of other trees and shrubs, many not well known, are keeping my farmden and beyond colorful longer.

Little known, for instance is Persian ironwood (Parrotia persica). I planted it years ago as a shade tree. Big mistake! For shade, that is. It doesn’t grow very large and is more of a large, multistemmed shrub. I’m glad I planted it, though. The smooth, gray stems grow thick and often horizontally, then downward a little before heading skyward, sort of like a miniature beech.

But I’m writing about color, and Persian ironwood has it, the leaves emerging purplish in spring, turning a lustrous green in summer, then morphing into variable shades of yellow, orange and red in autumn.

But I’m writing about color, and Persian ironwood has it, the leaves emerging purplish in spring, turning a lustrous green in summer, then morphing into variable shades of yellow, orange and red in autumn.

Also not well known is Korean mountainash (also called Korean whitebeam, Sorbus alnifolia). It’s closely related to more familiar mountainashes except in a different subgenus, Aria, with simple, rather than compound, leaves. I first saw this tree one fall at the Scott Arboretum in Pennsylvania and, knowing the tiny fruits make a good nibble, ate some. And knowing a whole tree can be grown from a tiny seed, I saved some seeds for planting.

That was in 2006, and the tree is now about 20 feet tall and draped in rusty red leaves that are splashed with yellow. As with the sugar maples, the color is particularly good this year — and fruits, which I’ll be nibbling, are also particularly abundant. As an added plus, the tree, each spring, is draped in large clusters of foamy, white flowers.

Another rare bird is Japanese stewartia (Stewartia pseudocamellia) which I planted — was it for its bark, for its flowers, or was it for its autumn leaf color? All are outstanding. The bark exfoliates in the same way as does sycamore, leaving silvery gray and charcoal gray patches against a khaki background. Its cup-shaped, white flowers with yellow center are like camellias, a relative. Right now, the leaves are a warm terra cotta color shading, in parts, to yellow.

Stewartia

Fothergilla (Fothergilla gardeneii) is one more lesser known plant now aglow here. This small shrub’s leaves’ traffic-stopping, rich red color is heightened by occasional blushes of yellow and dark red. Back in spring, candles of fragrant, creamy white flowers perched atop the ends of stems.

Known for Their Fruits

Some plants that I grow for their fruits are also more than earning their keep with fall color.

Huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata) is among the best of these, and the color makes up for its relatively poor yield of fruit. The deep red leaves look pretty highlighted among the evergreen leaves of rhododendron, mountain laurel, and lingonberry in my “heather bed.” (All are in the Heather Family, Ericaceae.) Where the plants are really spectacular is in the Shawangunk Mountains that rise up just west of here. There, whole swaths of plants paint the forest understory red.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is another fruit plant here, this one with many tropical aspirations. Tropical aspirations? It’s the northernmost member of the mostly tropical Custard Apple family (Annonaceae); its fruit has taste and texture reminiscent of banana; the fruits hang in clusters like bananas; and its long, drooping leaves would be visually at home in tropical climes. Come fall, the plants shed those tropical aspirations as the leaves turn clear yellow, especially nice when backlit by sunlight.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is another fruit plant here, this one with many tropical aspirations. Tropical aspirations? It’s the northernmost member of the mostly tropical Custard Apple family (Annonaceae); its fruit has taste and texture reminiscent of banana; the fruits hang in clusters like bananas; and its long, drooping leaves would be visually at home in tropical climes. Come fall, the plants shed those tropical aspirations as the leaves turn clear yellow, especially nice when backlit by sunlight.

I often rave about blueberry for its ease of growth, its pretty, white flowers in spring, its long season of harvest, its health benefits, and of course, its delicious fruits. I’m sure I’ve also mentioned its fall color, to me one of the best of all plants, mostly crimson but depending on the variety and the season, also with some yellow.

(I delve into the planting and use of these and other ornamental fruit plants in my book Landscaping with Fruit.)

Look Down

Perhaps it was a couple of particularly cold nights, with temperatures dropping into the low 20s, that caused leaves to all of a sudden drop all at once from certain trees. At any rate, the beautiful carpets blanketing the ground beneath these trees have caught my eye.

Pawpaws, for one, the overlapping, large leaves thoroughly hiding the grass beneath them.

Even at their best, mulberries leaves are nothing to look at in fall (but the trees do have other ornamental attributes, so did make it into Landscaping with Fruit). This year, though, the green leaves that plopped onto the ground following the cold nights did catch my eye. Perhaps it was the low angle of the sun reflecting off them; perhaps it was their shine.

One tree whose leaves are perhaps at their best on the ground in ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba). This one is edible, allegedly delicious, but did not make it into my book. The edible part is the nut (seed) inside the fruit. The problem, for me, is that the fallen fruit smell like an open sewer. Really!

The way around this is to forgo the fruit by planting a male tree. The fan-shaped leaves of this living fossil, whose appearance dates back to the Early Jurassic, turn the clearest yellow imaginable in fall. They’re at their best when they drop, making the ground look as if a sunbeam had fallen from the sky.

I haven’t — yet? — grown ginkgo myself.

ABOUT PEPPERS

/23 Comments/in Vegetables/by Lee ReichBetter Late than Never

Cold has finally gotten the better of my pepper plants. Two below freezing nights a month ago started their demise, and two more during the last few nights finally finished them off for the season. Not the fruits, though, plenty of which are piled and spread out in trays and baskets in the kitchen.

Outdoors, fruits weathered the below freezing temperatures well. They’ve been shielded from the full brunt of cold by their canopies of increasingly floppy leaves. Also, fruits of plants are higher in sugars than are the leaves. Thinking back to high school chemistry, I recall that any solute, such as sugar, lowers the freezing point of the solution. So pepper fruit cells can tolerate more cold than pepper leaves.

Even with the plants dead outside, the pepper season isn’t over here. The season has been greatly extended by harvesting and bringing indoors sound, green peppers showing any bit of red — or yellow if that’s the pepper’s ripe color. Sitting in trays and baskets in the kitchen, these mostly green peppers have been ripening, depending on when they were harvested and how long they’ve sat, to fully red or yellow color, when they are most flavorful (to me).

For some reason, perhaps the heat interfering with pollination, peppers started ripening later in the season than usual. The present and the past few week’s abundance of them makes up for the late start.

Thank You C2H4

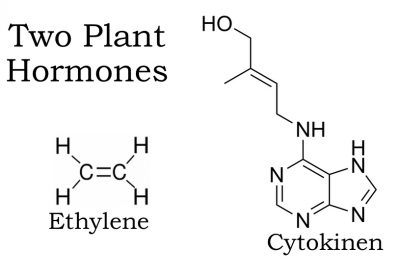

For the peppers’ morphing from green to red or yellow, I have to thank, in large part, a simple gas made up of just two atoms of carbon and four atoms of hydrogen. It’s ethylene, a plant hormone. Most plant and animal hormones are much more complex molecules.

Ethylene is produced naturally in ripening fruits, and its very presence — even at concentrations as low as 0.001 percent — stimulates further ripening. The ethylene given off by ripe apples can be used to hurry along ripening of tomatoes, by placing an apple in a closed bag with the tomatoes.

Banana, apple, tomato, and avocado are among so-called climacteric fruits, which undergo a burst of respiration and ethylene production as ripening begins. These fruits, if picked sufficiently mature, can ripen following harvest.

Peppers, along with “figs, strawberries, and raspberries are examples of non- climacteric fruits, whose ripening proceeds more calmly. Non-climacteric fruits will not ripen after they’ve been harvested. They might soften and sweeten as complex carbohydrates break down into simple sugars, but such changes might be more indicative of incipient rot rather than ripening or flavor enhancement.” Or so they say. And, I admit, I’ve said; that quote is from my book The Ever Curious Gardener. (The rest of the section about ethylene in my book is correct.) They and I were wrong.

So, I’ve learned two things. First of all, pepper do ripen well after harvest, not only to a bright color but also to a delicious flavor. And second, further reading has revealed that hot peppers, but not sweet peppers, are, in fact, climacteric fruits.

What about semi-hot peppers? Or non-hot hot peppers? (Read on.)

Hot and Not

I did also grow some semi-hot peppers this season. Roulette is a variety billed as resembling “a traditional habanero pepper in every way (fruit shape, size and color, and plant type) with one exception – No Heat!” Roulette had an interesting flavor that I both liked and didn’t like (mostly liked), and occasional ones did have some heat to them, but that might have been due to their proximity to . . .

Red Ember is billed as an early ripening hot pepper with “just enough pungency for interest.” It definitely caught my attention when I bit into one! Call me a wimp, but I thought it was fiery hot.

Peppers, Red Ember and Roulette

In my previously mentioned book, The Ever Curious Gardener, I also explored flavor in fruits and vegetables and, briefly, hotness in hot peppers. “Studies have been done with peppers, focusing specifically on their hotness, which, to muddy the waters, stems from not one, but from a whole group of compounds, capsaicinoids, mostly capsaicin and dihydrocapsain. Hotness in peppers was found to depend on the variety, the environment, and the interaction between variety and environment, with smaller fruited peppers less influenced by vagaries of the environment. Usually, but not always, a pepper will have more bite if plants are grown with warmer nights, with colder days, with just a little too much or too little water, or with fertility imbalances; increased elevation elicits the fiercest bite. Basically, with any sort of stress.”

Uncommonly hot temperatures this summer may very well have turned up the heat in Red Ember and put some heat in Roulette.

GRAPE and NUTS

/12 Comments/in Fruit/by Lee ReichLong-term Grapes

About a month ago, I picked a bunch of grapes as I was walking around the farmden with a friend, and handed it to him to taste. “Wow,” he exclaimed, eyes lighting up, “that really has taste.” That was the variety Brianna, one of many I grow that are otherwise not well-known, surely not to anyone who doesn’t grow grapes. My friend and I went on to agree that store-bought grapes are, “at best, nothing more than little sacks of sugary water.”

All that’s history now. Over the past month, most of the remaining grapes have either been harvested, eaten by birds or insects, or rotted, although a few very tasty berries can be salvaged here and there from some ugly bunches still hanging.

But are those grape-ful days gone yet? Years ago I read about how, over a century ago in France, fresh grapes were sometimes preserved by cutting off bunches along with a length of stem, the bottom of which was slid into a narrow-mouthed, water filled bottle. These bottles were then placed in a rack on shelves in cold storage which, where outdoor temperatures rarely dipped below freezing, was nothing more than a slightly insulated, outdoor room.

Grapes, fresh picked

A month ago, I emulated those French grape growers of yore, in this case using Corona beer bottles, three of them, three grape varieties, and my refrigerator — very decorative looking.

Grapes, after 1 month storage

For a modern version, another bunch of grapes went into the refrigerator in a sealed freezer bag.  If any of this worked out, the plan was to use either the old-fashioned or modern method with a whole bunch of bunches in my walk-in, insulated and with some cooling or heating, as needed, fruit and vegetable storage room.

If any of this worked out, the plan was to use either the old-fashioned or modern method with a whole bunch of bunches in my walk-in, insulated and with some cooling or heating, as needed, fruit and vegetable storage room.

Back in the olden days, storing fresh grapes was not so rare even on this side of the Atlantic. Professor Frank Waugh, in his 1901 book Fruit Harvesting Storing, Marketing, wrote “An acquaintance of mine from the grape-growing district wrote me the other day (March 12th), ‘A neighbor of mine has one hundred tons of Catawbas still in storage.’” Probably not as single bunches on stems in bottles of water!

Anyway . . . drum roll . . . yesterday it was time to taste my stored grapes. One variety, Glenora, didn’t hold up well. The other two, Lorelei and Brianna, were very good. “Bottled” bunches were very slightly shriveled, but tasted quite good. Perhaps they would do better in the more humid atmosphere of the walk-in cold storage room. The bagged bunch, Brianna, was plump and also tasty.

Admittedly, none of the stored bunches had the crisp texture or fresh flavor of the few berries hanging on ugly bunches still outside. But all were better than any fresh grapes I can buy.

Walnuts at the Car Wash

Storage of nuts, also abundant this time of year, is more straightforward. You pick them up from the ground, let them cure in a cool place away from squirrels, then crack and eat them at your leisure.

With black walnuts, the green husks must be removed and the nuts within cleaned up. Leaving the husks to soften and darken a little makes them very easy, although tedious, to remove. Of the many suggested methods, twisting them off with two rubber-gloved hands seems most effective.

As far as cleaning up the hulled nuts, an old fashioned washing machined, earmarked only for this purpose, would work well. I don’t have one, so came up with an effective alternative.

After spreading out all the husked nuts into eight black plastic vegetable harvest boxes, I loaded them in the back of my truck. And then it was off to the car wash. A couple of rounds with the high pressure water spray did the trick. It was a messy job that I was prepared for with rain coat and pants, boots, hat, and face shield. The truck needed a washing anyway.

Spreading out the trays on the deck exposed for a few days to bright sunlight had them all clean and dry. Squirrels would normally be a threat but the deck is also where Sammy and Daisy, my dogs, spend much of their days.

Previous generation watchdogs, Leila and Scooter, on deck

Finally, the nuts were put into five half-bushel baskets for cracking beginning towards the end of December, which is about when last year’s nuts will be finished up.

Harvest Tragedy

I was never that hopeful for English walnuts here (also called Persian or White walnuts). This species is not all that cold-hardy, their blossoms are susceptible to late frosts, which are common here on the farmden, their leaves are susceptible to anthracnose disease, and the only place I had for them was near the road, along the squirrel highway (telephone, cable, and electric wires).

Still, I couldn’t resist, back in 2006, an offer of seeds for some “hardy” varieties. I planted two groups of three trees each, planning to cull out any weaker ones in each group.

All the trees grew well, and I eagerly awaited blossoms which, finally, this year, appeared in abundance. That abundance was followed by an abundance of nuts, and everything looked healthy. Then disaster, in the form of squirrels, struck. Every single nut was stripped from the trees.

Well, not every single nut. One nut was left, which I harvested, easily popped out of its husk, and let sit — cure — on the kitchen table for a couple of weeks. Then, with great fanfare, it was cracked open and eaten.

This year’s English walnut harvest

As luck would have it, I also had a bag of store-bought English walnuts with which to compare in taste. No contest. Store-bought tasted rancid in comparison.

Next year, in enough time before the nuts start to ripen, I plan to spray all the trees with a hot pepper spray.

Any other suggestions would be most welcome.