A HOUSEPLANT, AN “ALMOND,” AND PAPER

/1 Comment/in Houseplants, Vegetables/by Lee ReichEasiest Houseplant of All?!

What with the frigid temperatures and snow-blanketed ground outside, at least here in New York’s mid-Hudson Valley, I turn my attention indoors to a houseplant. To anyone claiming a non-green thumb, this is a houseplant even you can grow.

Most common problems in growing houseplants (garden plants also) come from improper watering. Too many houseplants suffer short lives, either withering in soil allowed to go bone dry between waterings, or gasping for air in constantly waterlogged soil. Also bad off yet are those plants forced to alternately suffer from both extremes.

The plant I have in mind is umbrella plant (Cyperus alternifolius); it requires no skill at all in watering. Because it’s native to shallow waters, you never need to decide whether or not to water. Water is always needed! The way to grow this plant is by standing its pot in a deep saucer which is always kept filled with a couple of inches of water. What could be simpler?

One caution, though. The top edge of the saucer does have to be below the rim of the pot. Umbrella plants like their roots constantly bathed in water, but not their stems.

Lest you think that umbrella plant sacrifices good looks for ease of care, it doesn’t. Picture a graceful clump of bare, slender stems, each stem capped with a whorl of leaves that radiate out like the ribs of a denuded umbrella.

The stems are two to four feet tall, each leaf four to eight inches long. A dwarf form of the plant, botanically C. albostriatus, grows only a foot or so high, and has grassy leaves growing in amongst the stems at the base of the plant. There’s also a variegated form of umbrella plant, and a wispy one with especially thin leaves and stems.

Umbrella plants aren’t finicky about care other than watering. They grow best in sunny windows, but get along in any bright room. As far as potting soil, your regular homemade or packaged mix will suffice. Umbrella plants like a near-neutral pH, as do most other houseplants.

Want More?

As the clump of stems ages and expands, they eventually get overcrowded in the pot, calling out to be repotted. You could move it to a yet larger pot, or make new plants by pulling apart, cutting if necessary, the large clumps to make smaller clumps and potting each of them separately.

One way wild umbrella plants propagate is by taking root where their leaves touch ground when the stems arch over. You can mimic this habit indoors if you want to increase your umbrella plant holdings without dividing the clump. Fold the leaves down around the stem with a rubber band, as if you were closing the umbrella. Cut the stem a few inches below the whorl of leaves and poke the umbrella, leaves pointing upward, into some potting soil — kept constantly moist, of course.

An Almondy Relative

Though you may be unfamiliar with umbrella plant, you probably have come across its near-relatives either in the garden or in literature. One relative is yellow nutsedge (C. esculentum), a plant usually considered a weed and inhabiting wet soils from Maine down to the tropics.

The edible nutsedge, also C, esculentum, usually called chufa or earth almond, is not invasive, at least in what I’ve read from many sources, and in my experiences growing the plants. It’s a perennial that has been cultivated since prehistoric times and was an important food in ancient Egypt.

But esculentum in the botanical name means “edible,” and refers to the sweet, nut-like tubers the plant produces below ground. I grow this plant, and now consider it quite esculentum, with a taste and texture not unlike fresh coconut.  The main challenge with this plant is clearing and separating the almond-sized tubers from soil and small stones.

The main challenge with this plant is clearing and separating the almond-sized tubers from soil and small stones.

Storage improves their flavor, but they must be dried for storage, at which point they become almost rock hard. Give them an overnight soaking and they’re ready to eat as a snack or incorporate into other edibles or drinkables.

Paper Plant

Umbrella plant’s other famous relative is papyrus (C. papyrus), a plant that once grew wild along the Nile River. In ancient times, papyrus was used not only to make paper, but also to build boats and as food. Papyrus looks much like umbrella plant, and being subtropical, also would make a good houseplant. But with stems that may soar to fifteen feet in height, except for the diminutive variety King Tut, this species is too tall for most living rooms.

The Egyptians never recorded their method for making papyrus into paper but the Romans learned the process from the Egyptians and Pliny the Elder, a Roman, wrote about it in the first century B.C.

Genuine, Egyptian papyrus

Here’s how: You put on your toga and sandals (the latter also once made from papyrus), and prune down a few umbrella plant stalks. Cut the stalks into strips and, after soaking them in water for a day, lay them side by side in two perpendicular layers. Make a sandwich of the woven mat surrounded on either side by cloth, to absorb moisture, surrounded on either side with pieces of wood, then press.

In Egyptian sunlight, you could figure on the paper being dry and ready for use after about three weeks. Cut it to size to fit your printer.

SOWING PEARS AND LETTUCES

/19 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichFor the Long Haul

Among the must-have tools for any good gardener are hope, optimism, and patience. I thought of all three last week as I was planting some seeds.

The first of these seeds especially emphasizes patience. They were a few pear seeds I saved from pears I had eaten. After being soaked for a couple of days in water, the cores were soft enough for the seeds to be squeezed out, after which they were rinsed, and then planted in potting soil.

I put the planted seeds near a bright window in my basement where the cool (about 40°) temperatures would, in a couple of months, fool the seeds into feeling that winter was over. They would sprout.

Given time, those seeds would grow to become pear trees and, given more time (ten years, possibly more) go on to bear fruit. Those seeds came from Bosc and Passe Crassane pears. The genetics of the resulting trees will represent the sexual union of egg cells within the flowers with whatever male pollen happened to fertilize those eggs. As a result, said trees would bear fruits different, and probably worse, than the fruits from which they were taken. (There’s less than 1 in 10,000 chance of a seedling apple tree bearing fruit as good or better than the fruit from the mother tree; the ratio for pears should be similar.)

Shortening the Long Haul, and Other Benefits

Grafted tree, this one NOT interstem

So why will I be wasting all that time nurturing these plants? Because they’re not for fruit. They’re for rootstocks, for grafting. Pears and most other tree fruits are very hard to root from cuttings, so are propagated by grafting a stem of a good-tasting pear low on a rootstock.

So-called “seedling” rootstocks make for very sturdy trees, well anchored and genetically diverse so some scourge can’t wipe out a whole bunch of equally susceptible, genetically identical trees. On the other hand, seedling rootstocks make for very large trees that are very slow to induce bearing in their grafted portions.

Enter from stage right: clonal rootstocks, that is, plants reproduced asexually (cuttings are one example of asexual plant propagation) so that all members of the clone are genetically identical. Some clonal pear rootstocks — with such unalluring names as Pyrodwarf and OH x F 87 — have been developed that make smaller grafted trees that also are quicker to come into bearing. (I delve more deeply into the nitty gritty of grafting in my book The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden.)

My plan is to make interstem trees, each one by grafting a 9 inch stem of one of the clonal rootstocks near the base of a seedling rootstock, and then some variety for eating, such as Passe Crassane, atop the clonal interstem. That 9 inch clonal interstem has the same good effects as if it was used as a rootstock, except that the interstem trees also have sturdy root systems and genetic diversity at their roots. Because plants grow from the tips of stems, the heights of the grafts above ground remain the same even as the tree grows.

Parts of interstem tree

I’ll do both grafts at the same time, next spring. I’m hopeful, optimistic, and have patience that I’ll be biting my first pears from these trees within 5 years.

Lettuce be Hopeful, Patient, and Optimistic

The other seeds for this week’s sowing were four varieties of lettuce. No, not for eventual outdoor planting, but for planting in the greenhouse in spaces that will open up where some of last autumn’s lettuce will have been harvested.

It’s chilly in the greenhouse, where temperatures drop into the 30’s at night and on cloudy days, too chilly for good sprouting of lettuce seeds.  So I sowed them in a 4×6 inch seed flat filled with potting soil, then moved the flat in front of a sun-drenched, living room window. Once the lettuce seeds sprouted, which was in a few days, I moved them to the greenhouse. Warmer temperatures are needed to sprout a seed than to grow a plant.

So I sowed them in a 4×6 inch seed flat filled with potting soil, then moved the flat in front of a sun-drenched, living room window. Once the lettuce seeds sprouted, which was in a few days, I moved them to the greenhouse. Warmer temperatures are needed to sprout a seed than to grow a plant.

The seedlings should not, of course, remained crowded in their mini-furrows in the flat. So once the seedlings grow a little larger, I’ll gently lift each one by its leaves, coaxing it up and out of the flat, and then lower the roots into a dibbled hole in one potting-soil-filled-cell of GrowEase. And so on, until each of the 24 cells has a small plant in it.

I use this same method to keep up a steady supply of lettuce and other seedlings all through summer, the plants typically needing about a month in the GrowEase before they’re ready to transplant into the ground. Not so in winter, with the sun still hanging low in the sky and greenhouse temperature still cool. I estimate that it won’t be until early March before the lettuces will be ready to plant in the ground in the greenhouse.

I use this same method to keep up a steady supply of lettuce and other seedlings all through summer, the plants typically needing about a month in the GrowEase before they’re ready to transplant into the ground. Not so in winter, with the sun still hanging low in the sky and greenhouse temperature still cool. I estimate that it won’t be until early March before the lettuces will be ready to plant in the ground in the greenhouse.

No matter; I’m hopeful, optimistic, and patient. And I’ll still be harvesting some of last autumn’s lettuce beyond that date.

LESS SALT IS BETTER

/15 Comments/in Soil/by Lee ReichWhat Does “Salt” Really Mean?

A few years back, one of my neighbors planted a hemlock hedge along the road in front of their house as a screen from the road. Sad to say, the future does not bode well for this planting. The hemlocks very likely will be damaged by road salt. And the prognosis is similar for those stately sugar maples that line so many streets.  Chemically, road salt — at least the more traditional “road salt” — is the same as the stuff in your salt shaker, sodium chloride. Either sodium or chloride ions can be toxic to plants. Chlorine is a nutrient needed by plants, but it is classed as a micronutrient, needed in minute quantities. Too much is toxic. Sodium is not at all needed by plants.

Chemically, road salt — at least the more traditional “road salt” — is the same as the stuff in your salt shaker, sodium chloride. Either sodium or chloride ions can be toxic to plants. Chlorine is a nutrient needed by plants, but it is classed as a micronutrient, needed in minute quantities. Too much is toxic. Sodium is not at all needed by plants.

In a broader sense, a “salt” is any ionic molecule, that is, a molecule of two or more atoms in which electrons, which are negatively charged, are donated from one atom to another. Who gets what depends on how easily an atom or atoms can lose one or more electrons and how hungry another atom or atoms is for those electrons. That ability to donate or be hungry for an electron depends on the number of positively charged protons in an atoms nucleus and the number and arrangement of electrons around the nucleus.

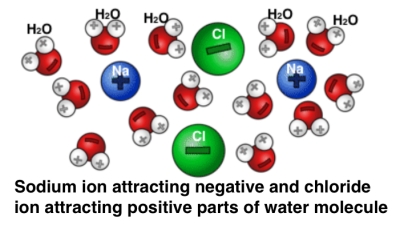

In the case of table salt, the sodium easily loses one electron and the chloride atom is hungry for it. The once neutral sodium atom becomes, after losing an electron, a positively charged sodium ion. The once neutral chloride atom, after gaining an electron, becomes a negatively charged chloride ion. And bingo, these two oppositely charged ions are strongly attracted to each other; they bond. What happens when water enters the picture? A water molecule, because of its shape has a slightly imbalanced charge distribution. The negatively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the sodium ion of table salt, and the positively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the chloride ion.

What happens when water enters the picture? A water molecule, because of its shape has a slightly imbalanced charge distribution. The negatively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the sodium ion of table salt, and the positively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the chloride ion.

Salt Problem in Winter, and Beyond

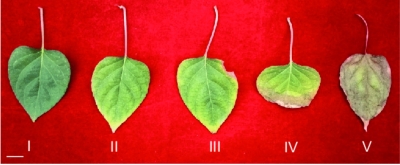

Any salt (ionic molecule), not only sodium chloride, attracts water so will simulate drought if in excessive amounts in the soil in the same way that potato chips dry out your lips. This leads to common symptoms of salt injury. First evidence of salt injury is browning of leaves, starting along the leaf margins. Early fall coloration and defoliation also can occur. More severe injury is manifest by twig or branch dieback, or death of a whole plant.

Progressive symptoms of salt damage

Salt also has an adverse effect on the soil itself, which is particularly insidious since it’s not as obvious as a dead plant. Over a period of time, sodium in salt can pull soil particles together, squeezing air out of the soil. As a result, roots suffocate.

Plants suffer most from salt in dry soils, so any plant exposed to salt in winter will benefit from mulching and watering during summer droughts. Watering also leaches sodium out of the soil, which improves soil porosity. Gypsum further aids in fluffing up a soil made too compact by sodium, by displacing sodium in the soil with calcium.

Honeylocust

Plants vary in their tolerance to salt. In addition to hemlock and sugar maple, the following trees and shrubs should not be planted where they will be exposed to salt: red maple, American hornbeam, shagbark hickory, dogwoods, winged euonymus, black walnut, privet, Douglas fir, white pine, crabapples, beech. Plants with a moderate tolerance to salt include: Amur maple, silver maple, boxelder, red or white cedar, lilac. Deciduous plants with high tolerances for salt include: Norway maple, paper and grey birches, Russian olive, honeylocust, white or red oaks, black locust, and many of the poplars and aspens.

For my neighbors who wanted an evergreen hedge, better choices would have been: white spruce, Colorado blue spruce, or Austrian pine. Perhaps even yew, since the site was somewhat shaded.

Mitigation or Avoidance

An obvious way to limit problems with road salt on plants, even salt that you might spread on your driveway or paths, is to use less salt, or none at all. (After once slipping on ice in my driveway and suffering a slight concussion, I became very aware of weighing damage to plants against damage to humans.) Fortunately, there are ways to keep all creatures happy.

Traction on ice or snow can be increased by spreading sand or sawdust.

A very effective technique, one that uses less salt, used by some road crews is to spray a salt solution on dry roads before a weather event that will bring slippery conditions.

When salt must be used, use a minimum amount or substitute a salt other than sodium chloride. Calcium chloride, for instance, is a salt that is only a tenth as toxic to plants as sodium chloride. One of the best materials as far as effectiveness with minimum damage to vehicles, concrete, and vegetation, is calcium magnesium acetate (CMA); but it’s expensive.

Salts that are fertilizers, such as ammonium nitrate or calcium nitrate, melt ice and at the same time nourish plants. Salts other than sodium chloride still need to be used with caution, for they can cause salt desiccation and/or nutrient imbalances in plants. My favorite treatment for icy conditions here at home is spreading wood ash. Effectiveness comes from the dark color absorbing sunlight to speed melting, a slight grittiness increasing traction, and its salt content. Of course, access to wood ash means you or an ash-rich friend burns wood for heat.

My favorite treatment for icy conditions here at home is spreading wood ash. Effectiveness comes from the dark color absorbing sunlight to speed melting, a slight grittiness increasing traction, and its salt content. Of course, access to wood ash means you or an ash-rich friend burns wood for heat.

For all its benefits, wood ash is a mess if tracked indoors. I take off my shoes or boots in the mudroom.