LESS SALT IS BETTER

/15 Comments/in Soil/by Lee ReichWhat Does “Salt” Really Mean?

A few years back, one of my neighbors planted a hemlock hedge along the road in front of their house as a screen from the road. Sad to say, the future does not bode well for this planting. The hemlocks very likely will be damaged by road salt. And the prognosis is similar for those stately sugar maples that line so many streets.  Chemically, road salt — at least the more traditional “road salt” — is the same as the stuff in your salt shaker, sodium chloride. Either sodium or chloride ions can be toxic to plants. Chlorine is a nutrient needed by plants, but it is classed as a micronutrient, needed in minute quantities. Too much is toxic. Sodium is not at all needed by plants.

Chemically, road salt — at least the more traditional “road salt” — is the same as the stuff in your salt shaker, sodium chloride. Either sodium or chloride ions can be toxic to plants. Chlorine is a nutrient needed by plants, but it is classed as a micronutrient, needed in minute quantities. Too much is toxic. Sodium is not at all needed by plants.

In a broader sense, a “salt” is any ionic molecule, that is, a molecule of two or more atoms in which electrons, which are negatively charged, are donated from one atom to another. Who gets what depends on how easily an atom or atoms can lose one or more electrons and how hungry another atom or atoms is for those electrons. That ability to donate or be hungry for an electron depends on the number of positively charged protons in an atoms nucleus and the number and arrangement of electrons around the nucleus.

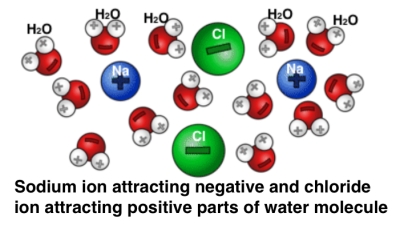

In the case of table salt, the sodium easily loses one electron and the chloride atom is hungry for it. The once neutral sodium atom becomes, after losing an electron, a positively charged sodium ion. The once neutral chloride atom, after gaining an electron, becomes a negatively charged chloride ion. And bingo, these two oppositely charged ions are strongly attracted to each other; they bond. What happens when water enters the picture? A water molecule, because of its shape has a slightly imbalanced charge distribution. The negatively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the sodium ion of table salt, and the positively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the chloride ion.

What happens when water enters the picture? A water molecule, because of its shape has a slightly imbalanced charge distribution. The negatively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the sodium ion of table salt, and the positively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the chloride ion.

Salt Problem in Winter, and Beyond

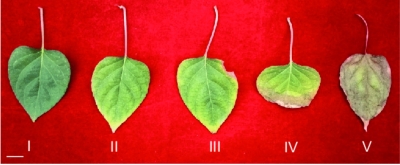

Any salt (ionic molecule), not only sodium chloride, attracts water so will simulate drought if in excessive amounts in the soil in the same way that potato chips dry out your lips. This leads to common symptoms of salt injury. First evidence of salt injury is browning of leaves, starting along the leaf margins. Early fall coloration and defoliation also can occur. More severe injury is manifest by twig or branch dieback, or death of a whole plant.

Progressive symptoms of salt damage

Salt also has an adverse effect on the soil itself, which is particularly insidious since it’s not as obvious as a dead plant. Over a period of time, sodium in salt can pull soil particles together, squeezing air out of the soil. As a result, roots suffocate.

Plants suffer most from salt in dry soils, so any plant exposed to salt in winter will benefit from mulching and watering during summer droughts. Watering also leaches sodium out of the soil, which improves soil porosity. Gypsum further aids in fluffing up a soil made too compact by sodium, by displacing sodium in the soil with calcium.

Honeylocust

Plants vary in their tolerance to salt. In addition to hemlock and sugar maple, the following trees and shrubs should not be planted where they will be exposed to salt: red maple, American hornbeam, shagbark hickory, dogwoods, winged euonymus, black walnut, privet, Douglas fir, white pine, crabapples, beech. Plants with a moderate tolerance to salt include: Amur maple, silver maple, boxelder, red or white cedar, lilac. Deciduous plants with high tolerances for salt include: Norway maple, paper and grey birches, Russian olive, honeylocust, white or red oaks, black locust, and many of the poplars and aspens.

For my neighbors who wanted an evergreen hedge, better choices would have been: white spruce, Colorado blue spruce, or Austrian pine. Perhaps even yew, since the site was somewhat shaded.

Mitigation or Avoidance

An obvious way to limit problems with road salt on plants, even salt that you might spread on your driveway or paths, is to use less salt, or none at all. (After once slipping on ice in my driveway and suffering a slight concussion, I became very aware of weighing damage to plants against damage to humans.) Fortunately, there are ways to keep all creatures happy.

Traction on ice or snow can be increased by spreading sand or sawdust.

A very effective technique, one that uses less salt, used by some road crews is to spray a salt solution on dry roads before a weather event that will bring slippery conditions.

When salt must be used, use a minimum amount or substitute a salt other than sodium chloride. Calcium chloride, for instance, is a salt that is only a tenth as toxic to plants as sodium chloride. One of the best materials as far as effectiveness with minimum damage to vehicles, concrete, and vegetation, is calcium magnesium acetate (CMA); but it’s expensive.

Salts that are fertilizers, such as ammonium nitrate or calcium nitrate, melt ice and at the same time nourish plants. Salts other than sodium chloride still need to be used with caution, for they can cause salt desiccation and/or nutrient imbalances in plants. My favorite treatment for icy conditions here at home is spreading wood ash. Effectiveness comes from the dark color absorbing sunlight to speed melting, a slight grittiness increasing traction, and its salt content. Of course, access to wood ash means you or an ash-rich friend burns wood for heat.

My favorite treatment for icy conditions here at home is spreading wood ash. Effectiveness comes from the dark color absorbing sunlight to speed melting, a slight grittiness increasing traction, and its salt content. Of course, access to wood ash means you or an ash-rich friend burns wood for heat.

For all its benefits, wood ash is a mess if tracked indoors. I take off my shoes or boots in the mudroom.

THE BEST HERB FOR A NORTHERN WINTER

/27 Comments/in Design, Houseplants, Soil/by Lee ReichCalamity Avoidance

A horticultural calamity averted. Again. Deb was snipping some leaves from our potted rosemary “tree” for salad dressing and said she noticed that the plant looked a little wilty. I was skeptical. Rosemary leaves are so narrow and stiff that they hardly broadcast their thirst. Still, quite a few rosemary plants have succumbed to winter drought here.

I checked the plant and, in fact, the leaves did look a bit wilty. The probe of my sort-of-accurate electronic moisture tester (which I nonetheless highly recommend) confirmed Deb’s diagnosis. The soil was very dry but, luckily, not to the point of killing the plant.

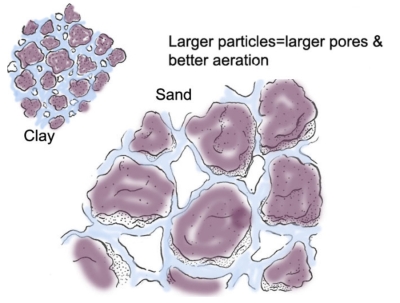

Allow me to digress . . . Soil scientists represent soil moisture levels with four descriptors. Right after a thorough watering, a soil is “saturated,” with all pores filled with water. Saturation is not desirable in the long term because roots need to “breathe” to do their work of drawing in nutrients and water, which is why plants exhibit the same symptoms from either dry or sodden soil.

Without additional water, gravity begins to pull water down and out of the larger pores of a saturated soil. Once gravity has pulled all the water it can from a soil, the soil is at “field capacity,” much to the pleasure of resident plants. At this point, large pores are filled with air yet some water, which is available for plants, is retained within smaller pores and clinging to soil particles.

Roots continue to slurp more and more water from the soil, but with increasing difficulty because water within even smaller pores and clinging even closer to soil particles is increasingly tightly held there by capillary attraction. Although the soil has moisture, it’s mostly inaccessible to plants. “Wilting point” has been reached.

Eventually, the only moisture left in the soil is that held very tightly in the very smallest pores and pressed tight against soil particles. That’s “permanent wilting point” from which, as the name implies, there’s no turning back. The plant will die.

The actual amount of water in a soil at any of these stages depends on the range of particle sizes in the soil. Clay soils have tiny particles, with tiny spaces between them, so have more water at wilting and permanent wilting point than do sandy soils, with their large particles and large pores.

At or near field capacity, sands have more air and less water than clays.

Where were we? Oh, my rosemary plant. I’m figuring it was just teetering on the edge of wilting point. Needless to say, I watered both my rosemary “trees.”

(For a lot more about soil water and how to make the best of it, see my book The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden.)

Dry Air, Moist (Enough) Soil

You’d think — I once did — that rosemary, because in the wild it billows down dry hillsides overlooking the Mediterranean, would be resistant to drought. It does tolerate dry air. But those wild plants’ roots are in the ground where they can forage far and wide for moisture; not so in a pot.

Also, my rosemary plants are coddled with relatively consistent warmth in winter and a potting mix rich in nutrients. Couple this with low light conditions, even near a south-facing window, and you get very succulent growth. I don’t know what rosemary plants growing on a Grecian hillside are doing now, but my plants are growing like gangbusters. All that succulent growth transpires lots of water, and is very susceptible to drought.

Left half of this rosemary expired last summer

Once my plants go outdoors in summer, their leaves mature and toughen and growth is less succulent. They do still need sufficient moisture, so I have drip tubes on a timer quenching their thirst (and that of other plants). Except, that is, when the timer’s battery needs replacing and I don’t notice it. That was last summer. The plants were not at the permanent wilting point but a number of branches, which I pruned off, dried up, dead.

In Praise of Potted Rosemary

All this is not to frown upon growing rosemary where it can’t survive winters outdoors. On the contrary, I consider rosemary to be the finest herb for indoor growing. Flavorwise, it packs a powerful punch, unlike chives, for example, a plant that needs to be practically decimated if you really want to flavor something with it. Merely brushing against my rosemary plant releases an aromatic, piney cloud.

Rosemary is also a very attractive houseplant whether grown as a scraggly shrub reminiscent of the wild plants in their native haunts, trained as dense cones, or — as are my plants — as miniature trees. The leaves retain a healthy, verdant look, unlike those of basil, which look sickly and out of their element in dry, relatively dark and cool homes in winter.

Rosemary also rarely suffers from any insect or disease problem.

And finally, properly cared for, rosemary is perennial so can provide aroma, flavor, and beauty for many, many years.

But you and I do need to pay close attention to watering.

Rosemary, with its compatriots, bay and citrus, in summer

A PEAR, 170 YEARS LATER

/10 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening/by Lee ReichA Luscious Fruit in Winter

All fruits did well this past season but it was especially a banner year for pears. Why do I mention this now? Because we’re still eating them and they are delicious. “Them” is actually just one variety — Passe Crassane, not a variety you’d find on a supermarket shelf, but which is available as a tree.

Timely harvest, storage, and ripening of pears melds art and science; since this was my first crop from Passe Crassane, I was wary as I sliced off a taste. It was like slicing through butter, a good omen. The flesh was “white, fine. melting, [sugary], perfumed, and agreeably sprightly,” to quote from The Pears of New York, U. P. Hedrick’s 1921 classic. Delicious.

The seed for this pear was sown, literally, by one Louis Boisbunel in Rouen, France in 1845. Ten years later, the tree showed its worth and the fruit made its debut. Passe Crassane is a winter pear that needs to be harvested mature — here, in early November — and then kept in cold storage for a couple of months to ripen to full flavor. Under ideal storage conditions, fruits keep well for months.

This variety was very popular in its century of origin, and its cultivation spread to Italy, Spain, Germany, and England. Commercially, stems were dipped in a red wax to prevent water loss during storage; those red-tipped stems became a signature of Passe Crassane. By the 20th century, Passe Crassane had fallen out of favor because of its susceptibility to diseases, including dreaded fireblight.

(My tree was struck by what I thought might be fireblight a year and a half ago, so I had drastically lopped it back well below what might have been blighted portions, planning to graft the stump to another variety. Fortunately, one older branch remained below the lopping and that branch, for the first time this past season, bore fruit, heavily. I’ll let the tree re-develop from one of the few watersprouts that shot skyward where the tree was lopped.)

The Hard Part of Growing Pears

Apple, cherry, and other common tree fruits are usually beset with pest problems that make them hard to grow. Not so for pears. The hard part about growing pears is knowing when to harvest them and then ripening them to perfection.

Yeh, yeh, I’ve read all about various indicators that show pears are ready for harvest: 1) When the fruit stalk separates easily from the stem as you lift and twist; 2) When the skin color lightens slightly; 3) When the small lenticels on the skin turn from white to brown; 4) When the first fruits start to drop. And, my favorite, recording the harvest date, once you get it right, and then harvesting on about that date every year.

Picking Seckel pear

No matter what the method, a pear should be firm, not at all soft, once ready for harvest. Pears ripen from the inside out. So fruit left on tree to thoroughly ripen is mostly brown mush on the inside by then.

All those indicators notwithstanding, I am much better at timely harvesting of pear varieties I’ve grown and harvested for a number of years.

So much for harvest; now for storage. On or near freezing is ideal. Cold temperatures slow ripening, and, for all except very early varieties, primes the fruit to begin ripening.

Ethylene, a natural, gaseous plant hormone can unduly speed ripening. Mature pears give off very little ethylene; not so for harvested apples and many other fruits, so keep these other fruits away from the pears unless a whole lot of pears are needed ready for eating soon. (I cover ethylene more thoroughly in my book The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden.)

Finally, on to ripening, which occurs as fruits are brought into warmth, ideally a cool room, 60-70 degrees F. I press a finger against the stem end of the fruit, and if there is any give at all, the fruit is ready for eating.

All this finickiness with harvest, storage, and ripening is unnecessary with Asian pears, which are different species from European pears. Let Asian varieties ripen thoroughly on the tree, meaning they remove easily with a lift and twist, and are fully colored. Then eat. Or keep them refrigerated, and get them out to eat whenever you’re so inclined.

Asian pear, Korean Giant