BREWING UP BATCH OF POTTING SOIL

/16 Comments/in Gardening, Soil/by Lee ReichPrime Ingredients for Any Potting Mix

Many years, my gardening season begins on my garage floor. That’s where I mix the potting soil that will nourish seedlings for the upcoming season’s garden and replace worn out soil around the roots of houseplants. Why do I make potting soil? Why does one bake bread?

There is no magic to making potting soil. When I first began gardening, I combed through book after book for direction, and ended up with a mind-boggling number of recipes. The air cleared when I realized what was needed in a potting soil, and what ingredients could fulfill these needs. A good potting soil needs to be able to hold plants up, to drain well but also be able to hold water, and to be able to feed plants. The key ingredients in my potting mix are: garden soil for fertility and bulk; perlite for drainage; and a mix of peat moss and compost for water retention.

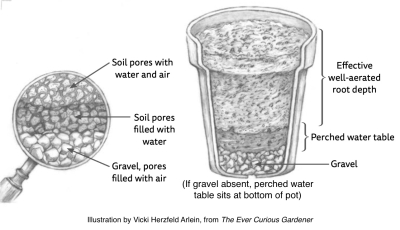

Why not just dig up some good garden soil? Because a flower pot or whatever container a plant is growing in unavoidably creates “perched water table” at its bottom. Garden soil, even good garden soil, is so dense that it will wick too much water up from that perched water table. Waterlogging is apt to result, and waterlogged soil lacks air, which roots need in order to function. (More about perched water tables and lots of other stuff about soil, propagation, plant stresses, and more can be found in my book The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden.)

Coarse mineral aggregates — perlite, in my mix — make potting soils less dense, so water percolates more readily into the mix, through it, and out the bottom of the container. Other aggregates include vermiculite, sand, and calcined montmorillonite clay (aka kitty litter). I chose perlite because vermiculite breaks down with time and can contain asbestos. Sand is heavy, although this can be an effective counterbalance for top heavy cactii.

The peat moss and compost in my mix are organic materials that slurp up water like a sponge; plants can draw on this “water bank” between waterings. One peat to avoid is “peat humus,” a peat that is so decomposed that it has little water-holding capacity. Organic materials also buffers soil against drastic pH changes and cling to nutrients which are slowly re-released to plant roots. Otherwise these nutrients run out through the bottom of seedling flats and flower pots.

Peat is relatively devoid of nutrients but the compost provides a rich smorgasbord of nutrients. And I can brew it myself. Just letting piles of autumn leaves decompose for a couple of years produces “leaf mold,” which has roughly the same properties as compost.

Potting soils made with garden soil and compost might need to be pasteurized to eliminate pests especially weeds. Too much heat should be avoided, however, because toxins which injure plants will form and beneficial organisms will be eliminated. When I am going to pasteurize, I do so only to the garden soil in the mix; my composts get to above 150°F all on their own.

To pasteurize potting soil, put it in a baking pan, bury a potato in it, and bake it in a medium oven. When the potato is baked, the soil is ready. Pasteurization is not absolutely necessary; I pasteurize to kill weed seeds.

What You Buy Isn’t . . .

Go out and buy a potting mix and, in all likelihood, that mix will be devoid of any real garden soil. You can mix up a so-called “soil-less” potting mix by sieving together equal volumes of peat moss and perlite. Since the mix has no garden soil or compost to supply nutrients, add 1/2 cup of dolomitic limestone, 2 tablespoons of bone meal, and 1/2 cup of soybean meal to each bushel of final mix. This mix has enough fertility for about a month and a half of growth without additional fertilizer.

I favor traditional potting mixes, which contain real garden soil. Real soil adds a certain amount of bulk to the mix, as well as a slew of nutrients and microorganisms. Real soil provides buffering capacity, which allows for some wiggle room in soil acidity.

The Magic Happens

I wrote early on, “There is no magic to making potting soil.” I could toy with ratios and make a potting mix from perlite plus compost, perlite plus compost plus garden soil, even straight compost, depending on the texture of the compost.

Going forward, I’m going to experiment with coir and/or PitMoss, both possible substitutes for peat moss, the harvest of which is environmentally questionable.

For my first batch of potting mix for this season, I’ll stick with my usual recipe. Step one is to give the garage floor a clean sweep.  Then I pile up on the floor two gallons each of garden soil, peat moss, perlite, and compost. On top of the mound I sprinkle a cup of lime (except if I’ve sprinkled limestone on the compost piles as I build them), a half cup soybean, perhaps some kelp flakes.

Then I pile up on the floor two gallons each of garden soil, peat moss, perlite, and compost. On top of the mound I sprinkle a cup of lime (except if I’ve sprinkled limestone on the compost piles as I build them), a half cup soybean, perhaps some kelp flakes.

This is a mixed bag of ingredients, but I reason that plants, just as humans, benefit from a varied diet. I slide my garden shovel underneath the pile and turn it over, working around the perimeter, until the whole mass is thoroughly mixed.  I moisten it slightly if it seems dry. When all mixed, the potting soil gets rubbed through a 1/2″ sieve, 1/4” if it’s going to be home for seedlings.

I moisten it slightly if it seems dry. When all mixed, the potting soil gets rubbed through a 1/2″ sieve, 1/4” if it’s going to be home for seedlings.

I end by clicking click my heels together three times and reciting a few incantations to complete this brew that has worked its magic on my seedlings, houseplants, and potted fruits each season.

TO PRUNE OR NOT TO PRUNE, THAT IS THE QUESTION

/3 Comments/in Pruning/by Lee ReichA Sharp Knife is not Enough

“Prune when the knife is sharp” goes the old saying. Wrong! (But don’t ever prune if the knife—or shears—is not sharp.) There are best times for pruning, and they depend more on the type of plant and the mode of training than on the sharpness of the knife.

Cat is ready to prune

As each growing season draws to a close in temperate climates, trees, shrubs, and vines lay away a certain amount of food in their above- and below-ground parts. This food keeps the plants alive through winter, when they can’t use sunlight to make food because of lack of leaves (on deciduous plants) or cold temperatures. This stored food also fuels the growth of the following season’s new shoots and leaves, which, as they mature, start manufacturing their own food and pumping the excess back into the plant for use in the coming winter.

A similar situation exists in some tropical and subtropical climates having alternating wet and dry, or cool and warm, seasons. Plants must wait out those quiet times drawing on their reserves.

Old apple tree, unpruned & pruned.jpg

When you prune a dormant plant, you remove buds that would have grown into shoots or flowers. Because pruning reapportions a plant’s food reserves amongst fewer buds, the fewer remaining shoots that grow each get more “to eat” than they otherwise would have and thus grow with increased vigor.

(For more details on above and what follows, see my book, The Pruning Book, available from the usual sources or directly from me, signed, at www.leereich.com.)

Summer or Winter, Growing or Dormant?

As the growing season progresses, response to pruning changes, because shoots of woody plants cease to draw on reserves and stems stop growing longer well before leaves fall in autumn. In fact, growth commonly screeches to a halt by midsummer. So the later in the growing season that you prune, the less inclined a woody plant is to regrow — the year of pruning, at least.

Traditional theory holds that summer pruning is more dwarfing than dormant pruning, but contemporary research puts this theory on shaky footing. True, if you shorten a stem while it is dormant — in February, for example — buds that remain will begin to grow into shoots by March and April, while if you cut back a shoot in midsummer, the plant might just sit tight, unresponsive. Ah, but what about the following spring? That’s when the summer-pruned shoot, according to this recent research, waits to respond. (Plants have an amazing capacity to act however they please no matter what we do to them.)

What are the practical implications of all this? First of all, if you want to coax buds along a stem to telescope out into shoots, prune that stem when it’s dormant.

Pollarded catalpa

On the other hand, summer is the time to remove a stem to let light in among the branches (to color up ripening apples or peaches, for example), or to remove a stem that is vigorous and in the wrong place. Watersprouts, which are vigorous, vertical shoots, are less likely to regrow if snapped off before they become woody at their bases.

Under certain conditions, summer pruning can be more dwarfing than dormant pruning, because regrowth following summer pruning can be pruned again. And again. Under certain conditions, summer pruning can also prompt the formation of flower buds rather than new shoots — just what you want for solidly clothing the limbs of a pear espalier with fruits or the branches of a wisteria vine with flowers.

Pear, before and after summer pruning detail

Red currant espalier before & after summer pruning

Unfortunately, the response to summer pruning depends on the condition of the plant as well as the weather. A weak plant may be killed by summer pruning. A late summer wet spell, especially if it follows weeks of dry weather, might awaken buds that without pruning would have stayed dormant until the following spring. Also factor just how much growth you lop off a stem as well as temperatures in the days or weeks following pruning.

Whose Health?

Regrowth and flowering are the dramatic responses to pruning; you also must consider plant health when deciding when to prune. Although immediate regrowth rarely occurs after late summer or autumn pruning, cells right at the cut are stirred into activity to close off the wound. Active cells are liable to be injured by cold weather, which is a reason to avoid pruning in late summer or autumn except in climates with mild winters or with plants that are very hardy to cold.

Dormant pruning just before growth begins leaves a wound exposed for the minimum amount of time before healing begins. Some plants — peach and its relatives, for example — are so susceptible to infections at wounds that they are best pruned while in blossom. On the other hand, the correct time to prune a diseased or damaged branch is whenever you notice it.

Also consider your own health (your equanimity and your energy) when timing your pruning. Depending on the number of plants you have to prune, as well as other commitments, you may not be able to prune all your plants at each one’s optimum moment. I prune my gooseberries in autumn (they never suffer winter damage), my apples just after the most bitter winter cold has reliably move on, and my plums (a peach relative) while they are blossoming.

Sap oozes profusely from cut surfaces of maples, birches, grapes, and kiwis if they are pruned just as their buds are plumping up in spring. The way to avoid this loss of sap is to prune either in winter, when the plants are fully dormant, or in spring, after growth is underway. The sap loss actually does no harm to the plants, so rushing or delaying pruning on this account is not for your plant’s health, but so that you can rest easy.

GETTING TO THE ROOT OF GARDENING

/2 Comments/in Design, Flowers, Fruit, Gardening/by Lee ReichEtymological Wanderings

Sure, I’ve been dropping seeds into mini-furrows in some seed flats, and prunings are starting to litter the ground outdoors. But there’s a lot of nongardening activity going on here. What better time to ponder etymology? (Etymology, not entomology, the latter of which is the study of insects; aphids, mealybugs and whiteflies, all of which will be crawling around soon enough.) What exactly do we mean when we talk about a “garden” or “gardening?”

Garden(?) in Italy

The word “gardening” is pretty much synonymous with “horticulture,” which comes from the Latin hortus meaning a garden, and cultura, to culture. According to Webster, horticulture is the “art or science of cultivating fruits, flowers, and vegetables.” The word “horticulture” was given official recognition in The New World of English Words in 1678 by E. Phillips, although though the Latin form, horticultura, first appeared as the title of a treatise of 1631.

Horticulture, then, is about growing fruits, flowers, and vegetables; nothing is said about cultivating a field of cotton or wheat. These latter crops are in the ken of agronomy, from the Latin root ager meaning field. Once again quoting Webster, agronomy is the “science or art of crop production; the management of farm land.” Horticultural crops are more intensively cultivated than farm crops — and more apt to be threatened by neglect.

In fact, “gardening” and “horticulture” are not exactly synonymous. Horticulture is usually associated with growing plants for a livelihood, and is broken down into pomology (fruits), olericulture (vegetables), floriculture (flowers) and landscaping. Gardening usually implies something more homey and intimate.

Gardyne Styles

Over the centuries, the word “garden” has been penned in many spellings. A chronicler of the 13th century wrote “gardynes,” in the next century Chaucer wrote the word a bit differently: “Yif me a plante of thilke blessed tre And in my gardyn planted it shall be.” We see yet another spelling early in the sixteenth century: “My lord you have very good strawberries at your gardayne in Holberne.” Finally, by the time of Shakespeare, we have: “Ile fetch a turne about the Garden.” Here, “garden” at least, is spelt [sic] the moderne [sic] way.

The root of the word “garden” comes from the Old English geard, meaning fence, enclosure, or courtyard, and the Old Saxon gyrdan, meaning to enclose or gird.

Walled garden

These words are closely related to our modern words “yard,” “girth,” and “guard.” Medieval gardens were physically enclosed. My vegetable garden is too, but mostly as protection against rabbits that love my peas and beans, not against knights practicing their jousting or wild pigs roaming the fields. The medieval garden was against the house and protected by a high wall, or, perhaps a wattle fence.

Over the centuries, “garden” and “gardening” have come to mean more than the fenced medieval garden. The archetypal Persian garden is dominated by refreshing pools or fountains of water. In the Italian garden, we find trees and shrubs, and stone stairways, balustrades, and porticos.

Classic Italian garden

Grand parterres characterize the French style of gardening.

Parterres in French garden

About a hundred years ago, the increasingly grand style of gardening fell from favor as an Englishwoman, Gertrude Jekyll, came forward to laud and design gardens that emulated intimate, colorful, and informal cottage gardens. She wrote that the ” . . . first purpose of a garden is to give happiness and repose of mind, which is more often enjoyed in the contemplation of the homely border . . . than in any of the great gardens where the flowers lose their identity, and with it their hold on the human heart.”

And Today . . . ?

What does “garden” and “gardening” mean today? A few tomato and marigold plants, separated from the dwelling by an expanse of lawn? A woodland glen of ferns and bleeding hearts? More recently, “forest gardens” have incorporated edible plants in forest-ish settings.

A forest garden?

How about a knot garden of herbs within a white picket fence — in the medieval style, one might say?

The World Was My Garden, the title of the book by early 20th century plant explorer and botanist David Fairchild offers another perspective on “garden.” (I’ll change the “was” to “is,” though.) I’m not sure where my garden ends and whatever else grows within my property boundaries begins.

What’s the boundary of this garden?

I pick strawberries in my vegetable garden and grow Caucasian mountain spinach among my gooseberries. Grapevines clamber on the arbor over my terrace, and a stewartia tree, mountain laurels, and lowbush blueberries snuggle near the east side of my home.

And why stop at property boundaries?

Mountains “in” this garden

Buildings as part of this garden, NYC HIghline

A row of eighty foot tall pine trees peer over the tops of my pear trees from the far end of my neighbor’s property two houses away to the north. To the south my meadow ends at a sweep of another neighbor’s field, the more frequently mown grass of which undulate like waves in summer sunshine in contrast to the more upright asters, fleabanes, goldenrods, and monardas that stand upright among the grasses in my meadow.

To the south my meadow ends at a sweep of another neighbor’s field, the more frequently mown grass of which undulate like waves in summer sunshine in contrast to the more upright asters, fleabanes, goldenrods, and monardas that stand upright among the grasses in my meadow.

Further extending the boundary are gardens revisited in my memory and those I have yet to see.

My boundless garden