SPRING SEEDING: WHEN?

/4 Comments/in Vegetables/by Lee ReichTruth From a Thermometer

Stop by my vegetable garden this time of year and you might see one or more thermometers poking out of the ground. No, I’m not experimenting with a new way to monitor the soil’s health. Soil temperature can serve as a guide for timely sowing of seeds outdoors. Seed sown in soil that is too cold won’t germinate; just sitting there waiting for warmer weather, ungerminated seeds are liable to rot or be eaten by animals.

Lettuce, onion, parsnip, and spinach seeds can be planted earliest. They’ll germinate just about as soon as ice in the soil thaws. At the other end of the spectrum are seeds of melons and squash, which won’t germinate until the soil temperature reaches sixty-five degrees. The minimum temperature required for germination of other vegetable seeds is as follows: forty degrees for beets, cabbage and its kin, carrots, peas, chard, parsley, celery, and radishes; fifty degrees for sweet corn and turnips; and sixty degrees for beans, cucumbers, and okra.

The above listing gives minimum, not optimum, temperatures for germination. Optimum temperatures might be even thirty degrees higher than the minimums, as in the case of celery which germinates quickest at seventy degrees. Waiting for the optimum temperature isn’t advisable, though. To delay sowing until the soil temperature reached the optimum temperature for pea germination (seventy-five degrees) would result in a midsummer harvest, when hot, dry weather turns peas coarse in taste and texture.

The above listing gives minimum, not optimum, temperatures for germination. Optimum temperatures might be even thirty degrees higher than the minimums, as in the case of celery which germinates quickest at seventy degrees. Waiting for the optimum temperature isn’t advisable, though. To delay sowing until the soil temperature reached the optimum temperature for pea germination (seventy-five degrees) would result in a midsummer harvest, when hot, dry weather turns peas coarse in taste and texture.

But What Temperature is Best?

For indoor seeding in seed flats, I use an electric, thermostatically controlled heating mat, waterproof and made for seed germination. With so many different kinds of seeds to grow, I can’t be twisting the thermostat dial up and down to suit each seed’s optimum. The temperature remains set at about 80 degrees. Which is why lettuce sown a couple of weeks ago still hasn’t sprouted.

Each kind of seed also has a maximum temperature at which it will sprout. For lettuce, that’s about 80 degrees. I resowed a few days ago, setting the lettuce flat on the cooler greenhouse bench instead of the mat, and green leaves have already shown their faces. Other vegetable seeds notorious for sulking in the heat are parsnip, celery, and pea. Turnip is interesting for being eager to sprout anywhere in the broad range of 60 to 105 degrees!

For more details on temperatures needed for seed germination, as well as plant growing and charts and tables with lots of other stuff about growing vegetables, I highly recommend Knott’s Handbook for Vegetable Growers, available in hard copy or online.

Tips to Advance the Season

No need to twiddle your thumbs waiting for the soil to warm; the warming process can be speeded up. (I detail a number of ways to do this in my book Weedless Gardening.) A thick, organic mulch, though generally beneficial to the soil, insulates the soil and hence delays warming this time of year. So for early sowings, rake back the mulch to expose the soil to the sun. Once the soil is warm — about mid-June — replace the mulch to recoup its benefits.

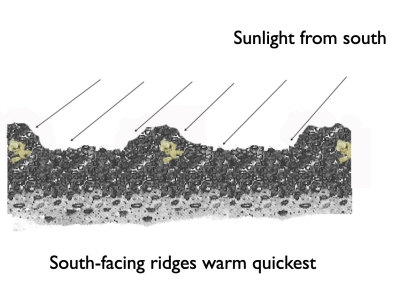

Where soil is not blanketed with mulch, warming can be hastened by forming small ridges oriented east and west. You plant seeds on the south faces of these ridges. With sunlight beaming directly down on these south-facing ridges, the soil there warms a bit faster than the surrounding soil.  (For the same reason, here in the Northern Hemisphere, south-facing slopes are warmer than north-facing slopes. North-facing slopes ideal for planting peaches and apricots to delay their flowers to when there’s less possibility of a later spring frost snuffing them out.)

(For the same reason, here in the Northern Hemisphere, south-facing slopes are warmer than north-facing slopes. North-facing slopes ideal for planting peaches and apricots to delay their flowers to when there’s less possibility of a later spring frost snuffing them out.)

Another way to warm the ground for early spring planting is to grow plants in raised beds. In raised beds the soil warms early because it’s more exposed to ambient air temperatures. Raised beds are well-drained, so dry more quickly; it takes more heat to warm a wet soil than a dry soil.

Changing the color of the soil surface affects its temperature. Black plastic mulch is unsightly, but it does warm the soil. Hide the plastic’s ugliness with a layer of bark chips and the plastic’s warming effect will be lost. In climates such as ours, where the soil is just marginally warm enough for vegetables like peppers, melons, and eggplants even in summer, the plastic mulch improves growth if left in place the whole season.

A top layer of compost on the ground darkens the soil in a more attractive manner than black plastic, though the effect on soil temperature is less dramatic. Compost does, of course, confer other benefits to the soil, such as improving the soil’s physical structure and providing essential nutrients. These benefits are lacking with black plastic.

Natural Indicators

All these techniques warm the soil a little faster than it would otherwise. You can measure the effect with a soil thermometer, but a thermometer is not mandatory for determining when to sow seeds. The soil slowly but surely warms up at about the same rate each spring, so you can sow by calendar dates, subtracting a few days if you deliberately hasten soil-warming.

Since the soil temperature and spring blossoms are influenced by the same general warming trend, even better is to sow seeds according to what perennial or woody plants are in bloom. For instance, you might plant peas just as the forsythias blossom, and corn according to the traditional indicator — when oak leaves are the size of mouse ears. A soil thermometer should register about forty degrees in the first case, and fifty degrees in the second.

Webinar planned: GROWING FIGS IN COLD CLIMATES

/1 Comment/in Fruit/by Lee Reich Yes, you can be picking fresh fruit from your own fig tree even if you live in a cold climate! I’ve grown figs for decades, beginning in Wisconsin and now in New York’s Hudson Valley.

Yes, you can be picking fresh fruit from your own fig tree even if you live in a cold climate! I’ve grown figs for decades, beginning in Wisconsin and now in New York’s Hudson Valley.

Figs can be grown successfully in cold climates because, among other things, they are adaptable plants and have unique bearing habits.

Learn various ways to get plants through cold winters, how to prune the plants, how to harvest the fruit, how to speed ripening, and more. If you already grow figs, this webinar will help you grow more or better figs, and be able to manage them more easily. If you haven’t yet experienced the rewards of growing figs, you have a treat in store for you.

Monday, June 6, 2022, 7-9 pm Eastern Time

Cost: $35

Registration is necessary; register and pay (credit card or Paypal) at:

https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_4hqKduDNSyiuRGPBlmBObg

SOMETIMES CALLED SPARROW GRASS, SOMETIMES ASPARAGOS

/20 Comments/in Vegetables/by Lee ReichMany Reasons to Grow Asparagus

In my book Weedless Gardening, I begin the section about asparagus with the statement “Forget about the usual directives to excavate deep trenches when planting one- or two-year-old crowns of asparagus.” More about planting in a bit; let me first lay out my case about why YOU should grow asparagus.

With most vegetables, by the time you taste them fresh-picked somewhere, it’s too late in the season to plant them in your garden. Not so with asparagus.  Borrow a taste from a neighbor’s asparagus bed, or from a wild clump along a fencerow, and you’re likely to want some growing outside your own back door. Minutes-old asparagus has a very different flavor and texture (both much better) than any asparagus that reaches the markets. The time to plant is now.

Borrow a taste from a neighbor’s asparagus bed, or from a wild clump along a fencerow, and you’re likely to want some growing outside your own back door. Minutes-old asparagus has a very different flavor and texture (both much better) than any asparagus that reaches the markets. The time to plant is now.

A big plus for asparagus is that it’s a perennial plant, so once a bed is planted, more time is spent picking than any other activity. An established planting can reward the gardener with tender green spears for a half a century or more. My asparagus bed is thirty-six years old and about twenty-five feet long; on every warm day, the bed offers enough stalks for a meal for two.

Deer and rabbits don’t have a taste for asparagus so no need to plant it within the vegetable garden or any protected area. (My dogs have eclectic palates, and they joined in on the harvest until I made clear that asparagus was not dog food.) Planting asparagus beyond the confines of the vegetable garden works out well because the lacy, green foliage stands as a backdrop for perennial flowers. Or, it can soften the line of a wall or fence.

Planting asparagus beyond the confines of the vegetable garden works out well because the lacy, green foliage stands as a backdrop for perennial flowers. Or, it can soften the line of a wall or fence.

Traditional Planting Method is Unduly Hard

Now, back to what I wrote about planting asparagus in Weedless Gardening, (available, by the way, at the usual sources as well as, signed, from my website, here).

The traditional method for planting an asparagus bed entails digging a trench a foot or more deep, setting the roots — one-year-old roots establish best — in the bottom with a covering of a shovelful of soil, then filling in the trench gradually as the stalks grew.

Whew! I planted my own asparagus bed just deep enough to cover the upward pointing buds from which the roots radiate, and the plants do just fine.

The main reasons for the traditional deep planting were to protect the crowns from overzealous hoes or other tillage implements, and from knives during harvest. But I don’t till my asparagus bed. I just pile on some mulch every year. And I harvest by snapping the stalks off with my fingers, rather than cutting into the soil with a knife.

Gardeners with patience sow seeds, which need a year more in the ground than roots before harvest can begin. Seed sowing is straightforward, except that germination is slow. Soak the seeds in water for a few hours before sowing to shorten germination time.

Whether starting with seeds or plants, the bed needs to be planted in full sun, with eighteen inches between plants in the row, and four feet between rows.

Tune into Asparagus’s Life Cycle

Although asparagus roots live on year after year, the feathery tops turn brown and die back to the ground every fall.  Then, when the spring sun warms the soil, energy stored in the roots fuels growth of the spears. As the spears grow higher and higher, feathery green branches unfold. Photosynthesis within these green branches pumps energy to the root system, energy that keeps the roots alive through the winter and fuels early growth of spears the following spring, thus completing the plant’s annual cycle. (The true leaves of asparagus, which are the small scales on the stems, are much reduced in size and function; the green stems take on most of the job of photosynthesis for this plant.)

Then, when the spring sun warms the soil, energy stored in the roots fuels growth of the spears. As the spears grow higher and higher, feathery green branches unfold. Photosynthesis within these green branches pumps energy to the root system, energy that keeps the roots alive through the winter and fuels early growth of spears the following spring, thus completing the plant’s annual cycle. (The true leaves of asparagus, which are the small scales on the stems, are much reduced in size and function; the green stems take on most of the job of photosynthesis for this plant.)

Harvesting asparagus steals some of the energy that had been stored in the roots. The plant must build adequate reserves before tender stalks can be spared for our plates, and then each season left enough time to grow freely to replenish its energy reserves.

The first season of planting, no asparagus is harvested; if good growth was made the first season, some can be harvested the second season. The plants are ready for a full harvest by the third season.

Full harvest means cutting all stalks from the time they first emerge until about the end of June.  Remember, the plants do need some time to nourish their roots in preparation for winter. Following the last harvest, all new green stems are left untouched until their summer job is over, as they turn brown in the fall.

Remember, the plants do need some time to nourish their roots in preparation for winter. Following the last harvest, all new green stems are left untouched until their summer job is over, as they turn brown in the fall.

Asparagus grew wild along the shores of the Mediterranean before plants were transplanted to Greek and Roman gardens. The steaming dish of asparagus on my table today is virtually identical to the asparagus enjoyed by the ancients over 2000 years ago. Even our word for the vegetable is nearly identical to, and derived from, the Greek word asparagos.

Asparagus came to America with the early colonists and has been cultivated extensively here since then. The red berries borne on female plants attract birds that spread the seed, so asparagus now pops up as an “escape” from cultivation along fencerows and roadsides.