OLIVE HARVEST IN FULL SWING HERE

/9 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening, Houseplants, Soil/by Lee ReichWhat To Do With This Year’s Harvest?

Olive harvest will begin — and end — here this week. Yes, it’s late. After all, the harvest in Italy was in full swing weeks ago, back in autumn. But this is the Hudson Valley, in New York. What do you expect?

I’m talking about harvesting real olives, not Russian olives (Elaeagnus angustifolia) or autumn olive (E. umbellata), both of which grow extensively in a lot of places, including here. Too extensively, according to some people, which is why they’re listed as “invasives” and banned from being planted in some regions. (But their fruits are very tasty, their flowers are very fragrant, their leaves are very ornamental, and their roots enrich the soil with nitrogen from the air, all of which garnered them a chapter in my book Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden.)

Present harvest here is of the true olive (Olea europaea), unrelated to the previously mentioned olives. Temperatures in the Hudson Valley, and beyond, would spell death to an olive tree, which is cold-hardy to about 14°F, so my tree is planted in a pot, just like my other Mediterranean-climate plants — fig, pomegranate, feijoa, black mulberry, bay laurel, kumquat, black mulberry, and Golden Nugget mandarin (tangerine). I can handle only so many potted, small trees, so it’s lucky that my olive doesn’t need a mate to bear fruit; it’s the self-fruitful variety Arbequina. The plant I got a few years ago from Raintree Nursery started bearing its first season!

Unlike my fig, pomegranate, and mulberry, olive is evergreen, so it needs light year ‘round. Fig, and company, are in a dark corner of my cold basement, dormant. The olive is in a cool room basking in sunlight from a south-facing window.

Two years ago, after an auspicious start, only one olive remained on the tree in late summer. I think my duck ate it.

This past fall, the harvest has increased many-fold — to almost a dozen fruits. What with being knocked around when moved indoors and the change in environment, about half that number of fruits now hang from the branches.

I like my olives fully ripe, black, so have let them hang as long as possible. Some are beginning to dry and shrivel, so it’s time to harvest. Fresh, the fruits are unpalatable, with a bitterness that comes from oleuropein. That bitterness is removed by curing and fermentation using lye, salt, and time. I’ve had naturally cured olives that use only the last ingredient, time, and that’s how I’m going to try mine.

For More Than Just Olive Fruits

A few years ago, I almost got rid of my olive tree. After all, it wasn’t making a dent in my olive consumption. Then someone pointed out that the olive, for thousands of years, has been a symbol of peace. That alone should be enough reason to keep the tree, and it was.

Also, the tree is pretty and long-lived — thousands of years, as documented by radiocarbon dating.

Secret Soil Recipe, Divulged (Again)

In preparation for the upcoming gardening season, I brought pails of frozen potting soil, compost, and soil in from the garage/barn. Soon I’ll need to trim back roots and repot some of those Mediterranean-climate fruits, including my Arbequina olive. Not my Meiwa kumquat, though, some of whose green fruits are showing hints of yellow, foreshadowing ripening to begin over the next couple of months. Trimming back its roots would cause branches to let go of fruits.

Potting soil will also be needed for the first seeds of the season, to be sown indoors in the next week or so.

I will now divulge my recipe for potting soil. The main ingredients are garden soil, compost, peat moss, and perlite. I thoroughly mix together equal volumes of these four ingredients, then add a cup of soybean or alfalfa meal (for extra nitrogen). If I’m feeling generous, I also throw in a half a cup or so of kelp meal (for micronutrients, although it’s probably superfluous with the panoply of nutrients from the compost). Perhaps also a half a cup of dolomitic limestone (for alkalinity, calcium, and magnesium, also probably superfluous with the buffering action and richness of the compost). Using wooden frames onto which I’ve stapled 1/2 inch hardware cloth, I sift together the mixture.

I will now divulge my recipe for potting soil. The main ingredients are garden soil, compost, peat moss, and perlite. I thoroughly mix together equal volumes of these four ingredients, then add a cup of soybean or alfalfa meal (for extra nitrogen). If I’m feeling generous, I also throw in a half a cup or so of kelp meal (for micronutrients, although it’s probably superfluous with the panoply of nutrients from the compost). Perhaps also a half a cup of dolomitic limestone (for alkalinity, calcium, and magnesium, also probably superfluous with the buffering action and richness of the compost). Using wooden frames onto which I’ve stapled 1/2 inch hardware cloth, I sift together the mixture.

Ten gallons of potting soil should carry me through winter until the compost piles and the soil have defrosted.

Olive Curing Update

Olives harvested and cured.

It’s now some days after I first wrote the above. Olives received no other treatment except being left to dry and wrinkle. Tasted them today — delicious! (I’m going to plan for bigger harvests for the future.)

CHERRIES JUBILEE (I HOPE)

/8 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening, Planning/by Lee ReichMore Plants?!?!?!

You’d think, after decades of gardening in the same place, that I by now would have planted every tree, shrub, and vine I could ever want or have space for. Not so! Every year I make up a “Plants to order” list, unfortunately before I hone down just where I’ll sink my shovel into the ground to prepare a planting hole.

Topping my list was Carmine Jewel cherry, a tart cherry that’s also good fresh. (Tart cherries often have higher sugar levels than do sweet cherries; but they also have tartness and other flavors that offset that sweetness.) The biggest draw for Carmine Jewel is its stature — no more, at maturity than 6 or 7 feet high. And a bush, not a grafted tree, so that if cold or deer nip back branches, new sprouts from ground level bear the same cherries that the rest of the bush does or did.

As a bush, Carmine Jewel is easy to net against birds, and easy to harvest. One big unknown is pest resistance and its flavor — that is, whether or not I will like it.

Some research indicated that Carmine Jewell is a hybrid of Prunus cerasus, which is the genus for conventional tart cherries, and P. fruticosa, a hardly edible cherry that offers bushiness to its offspring. It’s often listed, botanically, as P. X kerrasis, after Dr. Kerr who started this breeding line way back in the 1940s.

Carmine No, Juliet Yes

One benefit — to me — of this weekly column is that it forces me to research more deeply topics or plants that I might otherwise gloss over. Said research this week makes me cross Carmine Jewel off my “Plants to order” list.

Carmine Jewel, it turns out, has siblings. Among its siblings, it’s one of most tart. A newer group of siblings, the Romance series, were born in 2004, whose fruits are larger and sweeter. From this group, the variety Juliet was very productive and the sweetest. (Romeo was also quite good, but not as sweet.) So Juliet it is for me.

It remains to be seen just how good Juliet tastes, and how resistant it is to common cherry pests.

Nanking Cherries, All Good

Between the first paragraph and now I’ve figured out where to make Juliet home — in the “available seat” in the row of Nanking cherries (Prunus tomentosa) that line my driveway. This position will also make easy comparisons with the Nankings, one of the most reliable, tasty, care-free, and ornamental cherries I grow.

Nanking cherries, easy, good, quick to bear, prolific

Nanking cherries, despite snowballs of pinkish white blossoms every year, sometimes followed by frosts, have never failed to offer more cherries than we could possibly eat. I prune the bushes only to keep them from swelling to their 10 foot high and wide full size. The only downside to the fruits is that they are small. But they’re so good they earned themselves a whole chapter in my book Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden.

Choke(!)berry, Maybe

I recently learned that I may qualify to wear a longsleeve, blue T-shirt emblazoned with a large S. The S won’t stand for Superman, but for Supertaster. I sifted out this information with another fruit bush that was on my “plants to order” list: chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa).

About twenty years ago I planted a chokeberry bush. It fruited rather quickly, I tasted the fruit, spat it out, and dug up the plant.

A few weeks ago I was talking with a young farmer and after agreeing on the delectable flavor of black currants, he mentioned that chokeberry was another of his favorite fruits. “They’re awful,” said I. “Not if they’re cooked, frozen, or dried,” said he. Hmmm . . . chokeberry’s bite is from astringency, which, does dissipate when certain fruits — persimmons, for example — are cooked, frozen, or dried. Perhaps chokeberry needs a second chance here.

Then I started reading about supertasters, whose palates can be very sensitive to certain organoleptic sensations — astringency, for instance. I must be a supertaster because the slightest amount of astringency induces my spit reflex (which is why I grow Mohler and Szukis persimmon, both of which yield ripe fruits with hardly a hint of astringency). Reading more about chokeberry, it seems that those who like the fruit don’t mind, but actually enjoy, some astringency. So chokeberry is now on my “Plants to order, maybe” list.

Taste aside, chokeberry has much to recommend it. It’s a beautiful landscape bush, white blossoms in spring and, on many varieties, fiery red leaves in fall. It tolerates cold to below minus 30° F., and some shade. It’s also cosmopolitan about the soil in which it’s planted.

Chokeberry garners a lot of attention these days because its among the highest of any temperate zone fruit in both antioxidants and anthocyanins. The anthocyanins are one contributor to the astringency.

WINTER ‘SHROOMS, SUMMER DREAMS, & A WINNER

/10 Comments/in Flowers, Gardening, Planning, Vegetables/by Lee ReichMushrooms Think It’s Autumn Again

The 15 oak logs sitting in the shade of my giant Norway spruce tree more than earned their keep last year. Seven of them got inoculated with plugs of shiitake mushroom spawn in the spring of 2013; eight of the were inoculated in the spring of 2014. With little further effort on my part, reasonably good flushes of mushrooms appeared through spring and summer, then heavy flushes through fall until the mild weather turned frosty.

My friends Bill and Lisa, also shiitake growers, told me a few days ago how they’re still harvesting good crops, cold weather notwithstanding. They brought one of their logs indoors, where it stands in the sink of their laundry room. Great idea!

I don’t have a laundry room, but I do have a cool, dark, moist basement, i.e. mushroom heaven. So a few days ago I carried one of my logs down the narrow basement stairway and propped it against the wall in a dark corner near the sump pit. That nearby pit could catch excess water in case the log needed to be watered.

No watering was needed: A few days after taking up residence in the basement, fat, juicy shiitake mushrooms exploded from the plugs up and down the log — so many that we had enough to dry for future use.

I’ll leave the log down there to see if it flushes again. If nothing happens within a few weeks, I’ll carry it back under the spruce and replace it with another log from outside. The few weeks in the cool basement might be enough time for more mycelial growth in the log in preparation for another flush. And then, sitting for some time in cold weather beneath the spruce might be just what a shiitake log needs to shock it into another cycle of production.

Rotating the logs between the basement and beneath the spruce could keep us in fresh mushrooms all winter long.

Winter Green

Most years, by this time, piles of snow would make it difficult for me to get to those outdoor shiitake logs. Recent weather, and predictions for the coming months, makes me wonder if I should even keep using the word “winter.”

I’d sacrifice fresh shiitakes for a real winter with plenty of snow. (We have enough quart jars of dried shiitakes to last well into warm weather.) It’s nice to have that white stuff to ski on. Snow even fertilizes the ground (“poor man’s manure”) as well as insulates it against cold.

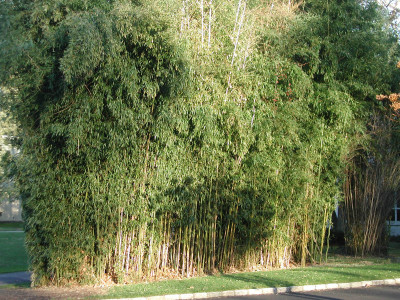

On the other hand, a mild winter has its appeal. Most winters, leaves and canes my yellow groove bamboo (Phyllostachys aureosulcata) are damaged — or, like last winter — killed back to the ground. The roots survive to re-sprout but the leaves turn brown and the new canes in spring are spindly. Some winters, like this winter probably, make for attractive (and useful) tall, thick canes dressed all winter long in green leaves.

Chester blackberry is another borderline hardy plant. It’s the hardiest of the thornless blackberries yet comes through most winter with many stems dried and browned — dead, that is. In the spring after our mild winters, stems are still green, foreshadowing a good crop of blackberries in late summer.

I’ve been waiting for a string of reliably milder winters to plant out my hardy orange plant (Citrus trifoliata). Yes, a citrus whose stems can just about survive to flower and fruit outdoors here, where winter temperatures normally plummet to minus 20°F or below. The fruit, sad to say, is only marginally palatable.

One more plus for a mild winter is the color green. The green of plants comes from chlorophyll, which is always decomposing, so must be continuously synthesized if the plant is to remain green. Synthesis requires warmth and sunlight, both at a premium during winters here. So most winters turn lawns muddy green or brown; even the green of evergreens, such as arborvitae, turn chalky green.

But not this winter — so far. Grass is still vibrant green, as are the arborvitaes and other evergreens.

My Favorites

My friend Sara asked me if I had yet ordered my seeds, and if I was getting anything especially interesting. Yes and hmmm.

As far as hmmm . . . I’ve tried a lot of very interesting plants over the years, too many of which — celtuce, garden huckleberry, vine peach, and white tomatoes, for example — were duds. So mostly, I restrain myself, devoting garden real estate to what I know either tastes or looks good, and grows well here in zone 5 or, more specifically, on my farmden. Some of my favorites include Shirofumi edamame, Blue Lake beans, Blacktail Mountain watermelon, Hakurei turnip, Sweet Italia and Italian Pepperoncini peppers, Golden Bantam sweet corn, Pennsylvania Dutch Butter Flavored and Pink Pearl popcorn, Lemon Gem marigold, and Shirley poppy.

I’m very finicky about what tomato varieties I plant, so won’t even mention them. Oh yes I will: Sungold, San Marzano, Paul Robeson, Brandywine, Belgian Giant, Amish Paste, Anna Russian, Valencia, Carmello, Cherokee Purple, and Nepal, to name a few.

And the Winner Is (drum roll) . . .

Thanks for all your comments, requested on last week’s post, about your soil care. Looks like you readers (or, at least, those of you who commented) are very savvy gardeners, enriching your soils with lots of organic materials. I chose one comment randomly fro the lot, the writer of which gets a free copy of my book Grow Fruit Naturally. Congratulations Selena.

For those of you who subscribe — or have attempted to subscribe to my weekly blog, a glitch is preventing you from getting email notifications. I just found out that the glitch has been glitching since back in September. I hope to get it fixed soon. Any suggestions? (The blog is in WordPress and subscriptions are with Feedburner, whatever that means). Stay tuned. If you want to just go to my blog site, new posts come out towards the end of every week.