Fahrenheit Obsession

/11 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichA Pillbox Relaxes Me

A little blue pillbox has solved my sleep problems.

I’ve touted the abundance of fresh figs I gather in summer and fall from my greenhouse, and the salad greens in winter. Not to mention the transplants for the garden in spring and summer.

All this has come at a price: sleep. In winter I often worry that something will go awry with the heater that keeps greenhouse temperatures from dropping below freezing, threatening the life of the in-ground fig trees and the salad greens.

And things have occasionally gone awry. One winter, the gas company didn’t deliver the gas for the propane heater on time. Another winter the pilot light kept going out on the heater. Another winter there was an interruption in electrical service, just a small amount of which is needed for the thermostat.

From the warmth of my home, how could I know if my plants were suffering so that I could take action? I set up a remote monitor with a secondary thermostat and a light bulb; if the greenhouse temperature drops below 35° F., I know it because the light goes on. Of course, I have to look outside at the greenhouse occasionally. And if I’m in bed on some cold winter night . . . a bicycle mirror mounted on the window lets me know if the light is on without my even having to lift my head. Of course, all bets if I am asleep, or if electrical service is interrupted.

Which brings me back to the blue pillbox. It’s filled with electronics, not pills.

SensorPush in greenhouse

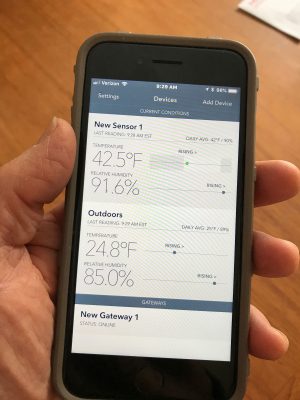

This device, sold as SensorPush, hangs on a nail in my greenhouse and continuously records temperature and humidity therein. No need for me to go to the greenhouse to communicate with it, though. It beams the information via bluetooth to my smartphone.

Better still, I can retrieve the information if my phone is beyond the approximately 325 foot bluetooth range with the help of the SensorPush Gateway. The Gateway connects via wi-fi to put the temperature and humidity information on the web and then on to my smartphone. From anywhere that I have cell service.

The Gateway connects via wi-fi to put the temperature and humidity information on the web and then on to my smartphone. From anywhere that I have cell service.

And even better, SensorPush can also alert my smartphone (and, hence, me) should the greenhouse temperature ever drop below (or above) whatever low (or high point) I set it at. The Gateway does require electricity. But Central Hudson has an alert feature to notify me, again via my increasingly smart smartphone, if the electrical service has been interrupted.

Checking Out the Weather, Continuously

I’m going to get another SensorPush to hang outdoors on one of the garden fenceposts. Knowing temperatures and humidity out in the garden is very useful to anyone who grows tree fruits.

Spring frosts threaten blossoms of fruit trees that bloom early in the season. Most threatened are apricots and peaches, but a season’s crop of apples, pears, cherries, or plums could also be snuffed out by a dramatic drop temperature.  Just how much cold kills these blossoms depends on the kind of fruit and the stage of blossoming. For instance, when apricot flower buds have just begun to swell and separate, they’ll laugh off cold down to zero degrees F. Once the petals begin to spread, the buds are killed at 19°F. When petals fall, 24° is lethal.

Just how much cold kills these blossoms depends on the kind of fruit and the stage of blossoming. For instance, when apricot flower buds have just begun to swell and separate, they’ll laugh off cold down to zero degrees F. Once the petals begin to spread, the buds are killed at 19°F. When petals fall, 24° is lethal.

So a SensorPush out in the garden would at the very least tell me whether to expect a crop from any of these tree fruits. Or to take action, like running outside to drape a blanket over a tree.

Knowing temperature and humidity can also predict the likelihood of disease. The spores of brown rot disease of plums, for instance, grow best in rainy weather with temperatures in the mid-70s during bloom or as fruit is ripening. Longer periods of wetness are needed at lower temperatures. Once again, such information can be used for prediction or action, in the latter case a preventative spray of sulfur, for example. (Sulfur, a naturally mined mineral, is an organically approved fungicide.)

A final nice feature of SensorPush is that it keeps records of the data it collects. The graphs it generates can be viewed on my smartphone or downloaded to a computer.

Now . . . if only I had an expensive art collection, a wine cellar, a reptile cage, or something else that needed close monitoring of temperature and humidity, I could justify another SensorPush.

Okay, now I’m going back to sleep, soundly.

Valentinic Communiqués

/3 Comments/in Flowers/by Lee ReichBe Careful What You Say/Send/Deliver

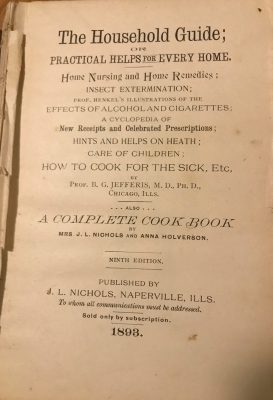

As you look online or peruse the seed and nursery catalogues that turn up in your mailbox, take note of those flowers that you might need to grow and preserve for the purpose of delivering messages for Valentines Day next year. For this year, fresh flowers from a florist will do. The Household Guide, or Practical Helps for Every Home (including Home Remedies for Man and Beast) written by Professor B. G. Jefferis, M.D., Ph.D. in 1893 serves as my reference on the language of flowers.

“Say it with flowers,” suggests the florist of today. Before presenting flowers, make sure you know what you are saying?

Everyone knows that a rose represents an expression of romantic love. But watch out! According to my little book, you had better heed what kind of rose you pull out from behind your back to present to the one you love. In the early stages of a romance, a moss rose (Rosa centifolia mucosa) such as Alfred de Dalmas or Général Kléber in bud might be an appropriate symbolic confession of love. Or you might use any white rose, which says something a little different: “I am worthy of you.” If you feel your lover glancing astray, a yellow rose will express your jealousy. For the relationship becoming stagnant, Doctor Jefferis prescribes Madame Hardy, York and Lancaster, or some other damask rose (Rosa damascena), meaning “beauty ever new.”

There is no better way to cement that budding romance than with an outstretched hand clasping a four-leaf clover, the plant that says “be mine.” Even in summer, you might spend all day on hands and knees looking for a four-leaf clover, and still never find one. Much more convenient is to substitute an oxalis leaf.  Though not related to clover, oxalis (Oxalis deppei, sometimes called the shamrock plant) leaves are dead ringers for clover leaves — except that all oxalis leaves have four leaflets. And better still, oxalis can be grown as a houseplant, affording you “four-leaf” clovers for year-round proclamations of affection.

Though not related to clover, oxalis (Oxalis deppei, sometimes called the shamrock plant) leaves are dead ringers for clover leaves — except that all oxalis leaves have four leaflets. And better still, oxalis can be grown as a houseplant, affording you “four-leaf” clovers for year-round proclamations of affection.

Later, if your amorous relationship turns sour, it is time to send (perhaps best not to hand-deliver this message) sweet-pea flowers. The message: depart. Sow sweet-pea early in the spring — April first around here, if you are in a rush for this message. And if you’re really in a rush, soak the seeds for 24 hours before planting.

Sentiments represented by other flowers may or may not be obvious. Forget-me-not, as expected, means just that. You might have suspected that witch-hazel represents a spell and that dead leaves of any kind represent sadness. But did you know that pansy represents thoughts . . . red clover industry . . . ferns fascination . . . golden rod caution . . . and orange blossoms chastity? One can only imagine what “dangerous pleasures” meant in 1893, but they were represented by the fragrant tuberose.

Dr. Jefferis further instructs us that flowers can be combined for greater depth of meaning. For example, a bouquet of mignonettes and colored daisies means “your qualities surpass your charms of beauty.” Yellow rose, a broken straw, and ivy together mean “your jealousy has broken our friendship.” And, a white pink, canary grass, and laurel” mean that “your talent and perseverance will win you glory.”

One caution when presenting flowers in person: Present them upright because an upside down presentation conveys the opposite meaning. Unless that is your intent.

Orchid Intimidation

/3 Comments/in Flowers, Gardening, Houseplants/by Lee ReichFear Not

I used to find orchids intimidating to grow. Their dust-sized seeds are fairly unique in not having any food reserves so — in the wild, at least — need the help of a fungus partner to get growing. And some orchids (epiphytes) spend their lives nestled in trees so need a special potting mix when grown in a pot. Orchids have above-ground structures called pseudobulbs. And many, especially those that call humid, tropical forests their homes, demand exacting environmental conditions that are very different from that found in most homes. Whew!

So I steered clear of growing any orchid for many years — until a local orchid enthusiast gave me a plant. After a couple of years, that plant, around this time of year, sent up a slender stalk which was soon punctuated with eight waxy, white flowers, each an inch across. For two months, those flowers greeted me each morning with their beauty and their delicious fragrance. Every year since, that plant has greeted me for weeks in midwinter.

Odontogl . . . a Mouthful

My orchid has no common name so needs to be referred to by its botanical mouthful, Odontoglossum pulchellum. (Even orchid names are intimidating, especially so because different genera have often been hybridized, and the resulting hybrid combines the generic names of the parents. So a hybrid with Brassavola, Laelia, and Cattleya in its parentage would have the name Brassolaeliocattleya. Now that’s a mouthful!)

Name notwithstanding, my Odontoglossum pulchellum has been easy to grow and get to flower.  The plant spends summers outdoors in semi-shade near the north wall of my house, and winters indoors on a sunny windowsill. I water it perhaps twice a week, unless I forget.

The plant spends summers outdoors in semi-shade near the north wall of my house, and winters indoors on a sunny windowsill. I water it perhaps twice a week, unless I forget.

Sounds like your run-of-the-mill houseplant, doesn’t it? So much for orchids being difficult.

The only special treatment my plant gets is a special potting mix. Odontoglossum pulchellum is an epiphytic orchard. Commercial potting mixes are available for epiphytic orchards but I make my own by mixing equal parts of my standard (home made) potting mix with equal parts wood chips. Nothing special about the chips; I just scoop them up from the pile that I use mostly for mulch that an arborist kindly dumps next to my woodshed every year.

Every spring I divide my orchid plant into 2 or 3 new plants, potting each new plant into its own pot with fresh potting mix.

More Orchids?

Odontoglossum pulchellum is an orchid that tolerates being treated like your average houseplant. And this is one of the most important points in growing orchids in a house: choose a sort that thrives in such an environment. Other orchids that will grow in the average home include phalaenopsis, paphiopedilums, and mini-catts, which are dwarf hybrids involving Cattleya (the corsage orchid).

Ideally, for flowering at least, certain conditions must be met. Most orchids enjoy bright light, which means setting the plant at an east, west, or south windowsill. From spring through autumn, light from a south window is too intense and may scorch foliage, so plants need to be protected with a thin gauze curtain, or moved to other windows or semi-shade outdoors.

Most orchids — again, for flowering — enjoy a ten to fifteen degree temperature difference from day to night, which is no problem in winter if you heat with a wood stove or already turn the thermostat down at night to conserve fuel. In the summer, the plant needs to be outdoors or else in a room that is not air-conditioned.

Even those orchids adapted to a home environment benefit from increased humidity. I raise the humidity around my plants by perching the flowerpot above a water-filled tray. Clustering plants together is another way to raise the humidity near plants, and also creates a visual lushness.

Once correctly sited, many orchids do not require inordinate amounts of care. Water requirements vary, but species with thickened pseudobulbs (bulbous stems), such as my Odontoglossum, get by with the least frequent watering. Orchid roots are susceptible to fertilizer burn, so the rule in feeding is to do it frequently and lightly. As with other houseplants, some orchid species take an annual rest, and at such times watering and feeding should commensurately diminish.

Since “mastering” the growing of one orchid, I have acquired another kind. This orchid is Dendrobium kingianum, which does go under the more user-friendly common name of pink rock orchid. I have also gotten this one to flower — but not every year.

This orchid is Dendrobium kingianum, which does go under the more user-friendly common name of pink rock orchid. I have also gotten this one to flower — but not every year.