HARDWOOD CUTTINGS: NOT HARD (TO DO SUCCESSFULLY)

/18 Comments/in Fruit/by Lee ReichPros for Hardwood Cuttings

Years ago, I had just one plant of Belaruskaja black currant. Now I have about a dozen plants of this delicious variety, and plenty of black currants for eating. Do you have a favorite tree, shrub, or vine that you would like more of.

Hardwood cuttings are a simple way to multiply plants. This type of cutting is nothing more than a woody shoot that is cut from a plant and stuck into the soil some time after the shoot has dropped its leaves in the fall, but before it grows a new set of leaves in the spring. In the weeks that follow planting, if all goes well, some roots may develop and, come spring, this apparently lifeless piece of stem grows shoots and more roots, and is well on its way to bona fide plantdom.

(Be very careful, though. Multiplying plants can become an addiction. I speak from experience.)

Easy to root

Success with hardwood cuttings depends on both your skills and the plant chosen. Not every woody plant is amenable to increase by hardwood cuttings. You can expect close to one hundred percent “take” with plants such as grape, currant, gooseberry, privet, spiraea, mulberry, honeysuckle, and willow. But this method generally is unsuccessful in making new apple, pear, maple, or oak trees.

Because they lack leaves, hardwood cuttings are less perishable than “softwood cuttings,” the leafy stem cuttings that are taken while plants are in active growth.

If you’re a novice and want to make your thumbs feel greener early on, try your hand with hardwood cuttings of willow, a plant I have seen take root from branches inadvertently left on top of the ground through the winter. Most other plants demand a little more finesse to ensure success with hardwood cuttings.

Gathering Wood

All right, so you have a woody plant you want to multiply by hardwood cuttings. Step back and look at the plant before you take wood for cuttings. Look for some young shoots, those that grew this past season; snip them off for cuttings. The shoots most likely to root are those of moderate vigor, not too fat and not too thin for the particular species.

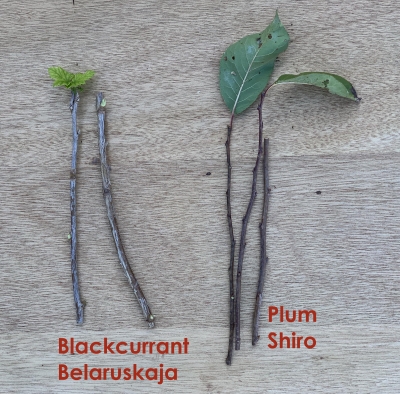

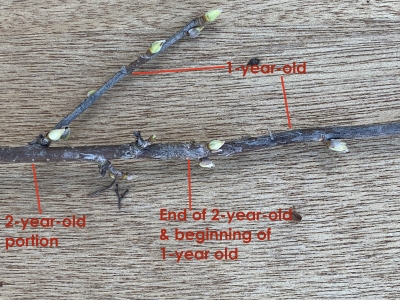

Black currant, 1 and 2-year old stems

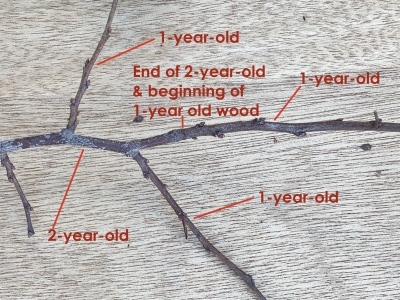

Plum, 2 and 1-year old wood

Once you have one or more shoots “of moderate vigor” in hand, cut them down to a manageable length of eight inches or so. Look for the nodes on each branch; these are the points where leaves were attached. Make the cut for the top of each cutting just above a node, and the cut for the bottom of each cutting just below a different node.

Make sure the upper end of the cutting, which is the point that was furthest from the root, is planted pointing upwards. The plant “remembers” this orientation and responds accordingly, growing roots from the bottom and shoots from the top of each cutting. (Although it’s not impossible to root upside down cuttings, there’s just less chance of success.) Professional propagators cut the bottoms off squarely and the tops at an angle so that the ends don’t get mixed up during planting.

Success Comes With . . .

Plant the cuttings in your garden where the soil is not sodden. Without good drainage the cuttings will rot, rather than root. Make a slit with your shovel, slide in a cutting until only the top bud is exposed, then firm the soil. The rooted plants should be ready for transplanting to their permanent homes by next fall.

Cuttings can be set in the ground for rooting either immediately or stored through the winter for setting out in early spring. I’ve had better success with fall, rather than spring, planting. In the spring, the cuttings often are overanxious to begin growth and the top growth is well underway before the roots have begun. The shoots soon realize that there are no roots to sustain them, then flop over and die.

With cuttings planted in the fall, roots have the opportunity to develop from now until the soil freezes. In the fall, soil temperatures drop more slowly than air temperatures so there’s still some time, depending on your location, before the soil freezes solid. New shoots, on the other hand, won’t grow until next spring, after they feel they have been exposed to a winter’s worth of cold. (This is a natural protection mechanism that prevents plants from resuming growth during a warm spell in January.) Come spring, the shoots that grow from the tops of the cuttings will already have at least the beginnings of roots to bring sustenance.

Blackcurrant cuttings in spring

Mulch fall-planted cutting so that alternate freezing and thawing of the soil doesn’t heave them out of the ground.

Cuttings could even be planted in pots with a well-drained potting soil, as long as the pots are kept cool (30-45°F) long enough for the shoots to “feel” winter, so they can grow shoots in spring.

If you’d rather plant in the spring, the cuttings need to be kept cool and moist through the winter. The traditional method of storage is to bundle the cuttings together and bury them upside down in a well drained soil. Why upside down? Because the bottoms of the cuttings then will be first to feel the warming effects of spring sunlight beating upon the ground, while the shoot buds are held in check buried deeper in cold ground.

A refrigerator can substitute for the traditional burying. Seal the cuttings in a plastic bag, wrap the bag in a wet paper towel, and then seal the whole thing in yet another plastic bag. Plant as early in spring as soil conditions permit.

Pay attention to what works and what doesn’t, figure out why, and you’re on your way to propagation addiction. Next worry is what to do with all your plants.

WHAT I LEARNED ABOUT BRUSSELS SPROUTS

/36 Comments/in Vegetables/by Lee ReichSprout Success

Years ago, a friend referred to Brussels sprouts as “little green balls of death;” that never exactly increased the gustatory appeal of this vegetable for me. The same could be said for “a little boiled to death,” a too common way of preparing the vegetable, and perhaps that’s what the friend had actually said.

Still, I’m always up for a horticultural challenge, even if I had never had success with Brussels sprouts. What does “lack of success” mean with Brussels sprouts? Dime-size sprouts.

Sit tight. This season my Brussels sprouts are a roaring success, and I’m going to impart to you what I learned about growing this sometimes maligned vegetable. Or, at least, what I did differently this year, which was a few things, so I’m not sure whether one or more of them was responsible for my achievement. It could even have been the weather, which I had no hand in.

Brussels sprouts is a very long season vegetable, so seeds need to be sown in spring for a fall harvest. Check. I planted mine back indoors in March for transplanting in May. They could have been sown a little later, at some sacrifice of yield.

A big difference in what I did this year was that the seeds that I sowed were those of a new variety, Catskill. Although a new variety for me, Catskill is actually an old variety, first introduced in 1941 by Arthur White, of Arkport, New York. It’s billed as yielding especially large sprouts (yes) on compact stalks (nope). In previous years I grew Gustus, Hestia, and Prince Marvel, and all were duds for me.

The Catskill mountains are only an hour’s drive away from my farmden, which perhaps explains my success with the same-named variety. But, as they often say (quietly) in advertising, “your results may differ.” My suggestion is to try a few varieties until you find one that does well wherever you garden or farmden.

Brussels sprouts requires a rich, near neutral soil high in organic matter. Check. My Brussels sprouts beds have always received, as do my other vegetable beds, an annual dressing of a one-inch depth of compost. Decomposition of compost enriches the soil with a variety of nutrients, including nitrogen.

Still, another big difference in what I did this year was to give my plants an extra oomph with, in addition to the compost, a sprinkling (1 pound per 100 square feet) of soybean meal, an organic source of nitrogen.

In anticipation or hope of large plants, each Brussels sprouts plant was afforded plenty of elbow room this year, with plants two-and-a-half feet apart down the middle of the three-foot-wide bed. They were flanked on each side by a single row of early carrots which, I figured, would be harvested and out of the way by the time the Brussels sprouts plants were spreading their wings (leaves).

My previous efforts with Brussels sprouts always resulted in three-foot-high plants that, early in their youth, flopped to the ground. Only after a plant’s supine stem had created a firm base would the end of its growing stem curve more or less upward, according to original plan. That youthful waywardness wasted and muddied lowermost sprouts, with the sprawling plant demanding even more space, which was a problem in my intensively-planted garden.

This year each plant had the companionship of a sturdy metal pole right from the get-go. Loops of string around the stalks and the stakes kept up with the plants’ upward mobility.

Pest Alert

Finally, and very important, is pest control, specifically of any one of the few leaf-eating caterpillars, colloquially called cabbage worms, which are the offspring of of those cheery, white moths that flutter among the plants on sunny days. The caterpillars also attack broccoli, cabbage, and cauliflower, all relatives in the cabbage family (Brassicaceae).

A very effective and nontoxic to most creatures (including to you and to me) control is spraying with Bacillus thuringienses, a naturally-occurring bacterium extracted from the soil. This material is more easily remembered under the name Bt, packaged up under such commercial names as Thuricide, Dipel, and Monterey B.t.

I checked the plants frequently through the growing season, at first just crushing any caterpillars I found and, only when the damage was getting severe, resorting to the spray. Cabbageworms, like any pest, can develop resistance to most pesticides, more likely the more that is used.

GMO. No

As an aside, that potential resistance of a pest to Bt is a problem with crops developed as genetically modified organisms wit Bt toxins. Almost all commercial corn and cotton have been genetically engineered in this way; the genetic material has also been incorporated into cotton, potato, rice, eggplant, canola, tomato, broccoli, collards, chickpea, spinach, soybean, tobacco, and cauliflower.

The problem arises because a field of plants expressing the Bt toxins is akin to that whole field being sprayed with Bt all season long. There is evidence of the development of resistance to Bt by insect pests of the genetically modified crop plants.

FERTILIZING 101

/20 Comments/in Soil/by Lee ReichFeed Sooner, Not later

Although shoot growth of woody plants ground to a halt weeks ago, root growth will continue until soil temperatures drop below about 40 degrees Fahrenheit. Root and shoot growth of woody plants and lawn grass are asynchronous, with root growth at a maximum in early spring and fall, and shoot growth at a maximum in summer. So roots aren’t just barely growing this time of year; they’re growing more vigorously than in midsummer.

Remember the song lyrics: “House built on a weak foundation will not stand, no, no”? Well, the same goes for plants. (Plant with a weak root system will not be healthy, no, no.) Fertilization in the fall, rather than in winter, spring, or summer, promotes strong root systems in plants.

Remember the song lyrics: “House built on a weak foundation will not stand, no, no”? Well, the same goes for plants. (Plant with a weak root system will not be healthy, no, no.) Fertilization in the fall, rather than in winter, spring, or summer, promotes strong root systems in plants.

By the time a fertilizer applied in late winter or early spring gets into a plant, shoots are building up steam and need to be fed. Fertilization in summer forces succulent shoot growth late in the season, and this type of growth is susceptible to damage from ensuing cold.

They Hunger For . . .

The nutrient plants are most hungry for is nitrogen. But nitrogen is also the most evanescent of nutrients in the soil, subject to leaching down through the soil by rainwater or floating off into the air as a gas. The goal is to apply nitrogen so that it can be taken up by plants in the fall, with some left over to remain in the soil through winter and be in place for plant use next spring.

Two conditions foster nitrogen loss as gas. The first is a waterlogged soil. If you’re growing most cultivated plants — yellow flag iris, marsh marigold, rice, and cranberry are some exceptions — your soil should not be waterlogged, aside from considerations about nitrogen. (Roots need to breathe in order to function.) Nitrogen also evaporates from manure that is left exposed to sun and wind on top of the soil. Manure either should be dug into the soil right after spreading, or composted, after which it can be spread on top of the soil, or dug in.

Leaching of nitrogen fertilizer is a more common and serious problem, especially on sandy soils. The way to prevent leaching is to apply a form of nitrogen that either is not readily soluble, or that clings to the soil particles. Most chemical fertilizers — whether from a bag of 10-10-10, 5-10-10, or any other formulation — are soluble, although a few are specially formulated to release nitrogen slowly.

The two major forms of soluble nitrogen that plants can “eat” are nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen. Nitrate nitrogen will wash right through the soil; ammonium nitrogen, because it has a positive charge, can be grabbed and held onto negatively charged soil particles. Therefore, if you’re going to purchase a chemical fertilizer to apply in the fall, always buy a type that is high in ammonium nitrogen. The forms of nitrogen in a fertilizer bag are spelled out right on its label.

The two major forms of soluble nitrogen that plants can “eat” are nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen. Nitrate nitrogen will wash right through the soil; ammonium nitrogen, because it has a positive charge, can be grabbed and held onto negatively charged soil particles. Therefore, if you’re going to purchase a chemical fertilizer to apply in the fall, always buy a type that is high in ammonium nitrogen. The forms of nitrogen in a fertilizer bag are spelled out right on its label.

Go Organic

Rather than wade through the chemical jargon, nitrogen loss through the winter can be averted by using an organic nitrogen fertilizer. Nitrogen in such fertilizers, with the exception of blood meal, is locked up and held in an insoluble form. As soil microbes solubilize the nitrogen locked up in organic fertilizers, it is released first as ammonium nitrogen. So by using an organic nitrogen source, the nitrogen is not soluble to begin with, and when it becomes soluble through the action of microbes, it’s in a form that clings to the soil particles and not wash out of the soil.

(Except in very acidic soils, other soil microbes then go on to convert ammonium nitrogen to nitrate nitrogen. This reaction screeches almost to a standstill at temperatures below 50 degrees Fahrenheit, so the ammonium nitrogen can just sit there, clinging to soil particles, until roots reawaken in late winter or early spring.)

Common sources of organic nitrogen include soybean meal, cottonseed meal, fish meal, and manure. Hoof and horn meal, leather dust, feather dust, and hair are esoteric sources, though plants will make use of them as if they were just ordinary, organic fertilizers. Even organic mulches, such as wood chips, straw, and leaves, will nourish the ground as they decompose over time.

The Cadillac of fertilizers is compost. Compost offers a slew of nutrients, in addition to nitrogen, released slowly into the soil as microbes work away on it. Compost — most organic fertilizers, in fact — are not the ticket for a starving plant that needs a quick fix of food.

Every year I spread compost an inch deep beneath especially hungry plants like vegetables and young trees and shrubs to keep them well fed. Less hungry plants get one of the above-mentioned organic mulches. The benefits of these applications continue, trailing off, for a few years, so annual applications build up continual reserves of soil nutrients, doled out by soil microbes, that translate to healthy plants and soil.

(More details about fertilization can be found in my book Weedless Gardening.)