FOR THE GARDENER WHO HAS EVERYTHING

/1 Comment/in Books, Fruit, Gardening, Tools/by Lee ReichHow Cold? How Humid?

Do you want to send a really good gift to a really good gardener? (Perhaps that gardener is you.) Problem is that most really good gardeners have pretty much everything they need except for expendables like string, seeds, or potting soil (unless they make their own. Don’t despair; I’ve come up with a few items many really good gardeners with (just about) everything they need might find useful.

At the top of my list is a nifty, little device with the odd name of Sensorpush. It’s not much bigger than an inch square pillbox, less than 3/4 inch thick, that you place wherever you want to monitor temperature and humidity — from your smartphone, via bluetooth.

Sensorpush, graph of the week’s outdoor conditions

Sensorpush, screen shot of current readings

Couple it with the WiFi Gateway and temperature and humidity can be monitored from anywhere on your smartphones. I periodically checked on my greenhouse and the outdoor temperatures here in New York when I was recently thousands of miles away in Israel.

SensorPush in greenhouse

My original use for the Sensorpush was for the greenhouse, to alert me, which it can do, if temperatures drop to a minimum that I set at 37°F. I now have another, outdoors, which alerted me to the one late frost (28°F) last spring which wiped out the crop on my peach tree. I may also put ones in my freezer and walk-in cooler.

All past information is available graphically and can be downloaded to a computer.

Water is Important

Much, much more low-tech is my new favorite watering can. It’s not any old blue watering can, it’s the French Blue Watering Can. It has everything I would look for in a watering can: hold lots of water, in this case 3 gallons; good balance when being carried and in use; and water exiting in a stream that’s gentle but not too slow. For optimum balance, get two, one for each arm.

Although the French Blue Watering Can now beats out my previously favorite Haw’s 2 gallon, zinc plated cans, which are, admittedly, more visually elegant, Haw’s is still in the running with their beautiful, copper-enameled, 2 quart watering can that I use mostly indoors. For indoors, it’s a good volume, and the long spout can reach in among plants for more pinpoint watering once its rose is removed.

Books, of Course

I can’t help but mention books. Those that I mentioned last week were general categories; the really good gardener has, of course, some very specific interests and expertises. And there are books for these (I’ll stay away from my special interests to avoid having to mention, once again, any of the books that I have authored).

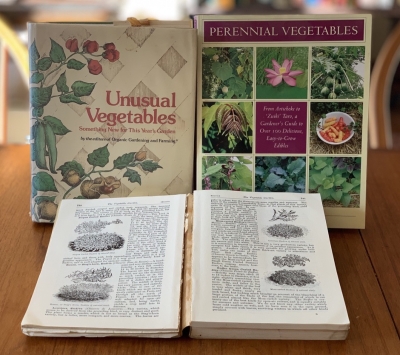

So, for instance, if you’re interest is in unusual vegetables, you could start with A. C. Herklots’ 1972 publication Vegetables of Southeast Asia. The book is especially rich in “greens,” including shepherd’s purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris), garland chrysanthemum (now Glebionis coronaria), and honewort (Cryptotaenia japonica). Also a slew of “Asiatic cabbages.” For something even less contemporary, there have been various printings of The Vegetable Garden by Vilmorin-Andrieux,scion of the famous French seed company. In addition to many common vegetables, of which many interesting varieties are mentioned, ferret around in the book and you’ll also find some unusuals: olluco (Ullucus tuberosus), rampion (Campanula Rapunculus), and seakale (Crambe mariitima).

Eric Toensmeier’s Perennial Vegetables offers a much more contemporary take on unusual vegetables. Most of the vegetables mentioned are not really perennial in cold climates but they surely are unusual. The last I heard, very few people were growing nashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum), Chinese artichoke (Stachys offinis), chufa (Cyperus esculentus var. sativa), or winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonobolus).

Tools and Plants

Finally, I’d like to give a shout out to the five advertisers on my blog posts (to your right). These are not just any old companies that choose to advertise. They represent businesses whose products and, in some cases, owners I know and trust (by experience) to offer the highest quality products.

Let’s start with the two nurseries. Looking for a place to buy high quality plants of pawpaw, persimmon, quince, medlar, or even more common fruits. Raintree Nursery is the one. I’ve even sent them stems from some of my more unique plants to propagate. Cummins Nursery is the go to nursery for a very wide selection of varieties of apple, pear, peach, and other familiar tree fruits on a variety of rootstocks. The rootstock helps determine such tree characters as size, adaptability to various environments as well as how soon and how much fruit you’ll pick.

(Incidentally, a nursery tree grown hundreds of miles away can be just as adapted to your site as one grown around the corner. Genetics is important, so an Ashmead’s Kernel apple grown in Washington is genetically identical to one grown in New York, or anywhere else.)

With all those new plants, some tools will be needed to help care for them. For everything from high quality soil sampling tubes to grafting supplies to hoes to tripod ladders (very stable, I own two different sizes), look to Orchard Equipment Supply Company (OESCO).

If you’re looking very specifically for cutting tools — pruning shears, pruning saws, loppers, pole saws, and the like — look no further than ARS. You can’t go wrong purchasing an ARS tool. After writing a book about pruning, I was sent many samples of pruning equipment; among the shears, ARS — specifically the VSX Series Signature Heavy Duty Pruner — is my favorite, with good weight, good steel, replaceable parts, and easy opening with just a firm squeeze of the handles. They slightly edged out my Felco and Pica shears.

Scythe Supply sells just one thing: scythes. But they offer the best of the best, as well as sharpening services and instruction. Don’t expect one of those picturesque, old scythes often turning up at garage sales, more useful for decorating a barn wall than cutting tall grass. Scythe Supply scythes are super light and well balanced with blades hammered razor sharp like those of Samurai swords. One-time Congressional candidate, homesteader, and swinger of a scythe into his nineties, Scott Nearing had this to say about scything: “It is a first-class, fresh-air exercise, that stirs the blood and flexes the muscles, while it clears the meadows.” So true. I use my mowings for compost and mulch.

THE GIFT OF EXPERIENCE, OTHERS

/13 Comments/in Books, Gardening/by Lee ReichREAD ALL ABOUT IT

I’ve heard wizened gardeners boast at how many years they’ve been gardening, impressing newbies with their unspoken knowledge. I’ve never been much impressed by anyone’s years gardening as an indicator of horticultural prowess.

I speak from experience: I’ve swung a scythe for many decades, which may lead others to believe me to be a long time expert scyther. Not so. A few years ago, after 25 years of scything, I learned I was using it incorrectly. (Unfortunately, earlier on I had the hubris or ignorance to describe it and its use for a magazine article which included a sepia-toned photograph of me swinging it — wrong, I subsequently learned).

On the other hand, as a newbie gardener I had access to one of the best agricultural libraries in the country (I was in graduate school in agriculture at the time), and voraciously devoured its holdings. After only a couple of years of gardening and reading, I had — in all modestly — a vegetable garden to vie those of much more seasoned gardeners.

Most gardeners pretty much do what they’ve done year after year. Even if new techniques, tools, and plants were tried annually, it would take a long time to make sense out of all of it. Enter books, a streamlined way to garner “experience.” Not firsthand, of course, but a way to learn from the successes and failures of others who chronicled their horticultural ups and downs. Also a way to learn more generally about what makes gardens tick, the soil types, the insects, the climates, the many plants that you or I may never grow — nor, perhaps, want to after learning about them. It all makes for a better and more resilient gardener.

BOOKS, FROM THE GROUND UP

Over the years I have both purchased and been sent review copies of many, many gardening books. As I look over my bookshelves I see a number of them — some old, some new — that, in my opinion, would be must-reads for gardeners, beginning or otherwise. Interestingly, none of the titles have the word “organic” in them. Not to worry; any good gardening is organic.

The following books can’t help but represent my biases for writing styles and interests. Still, I’ve forced myself to leave out some favorites because they’re neither foundational nor perhaps would be generally of interest.

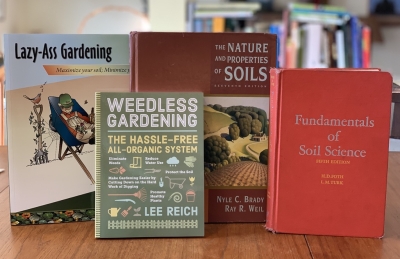

Good gardens start from the ground up, so let’s start with some books about soil. For the basics, see Robert Pavlis’ Soil Science for Gardeners: Working with Nature to Build Soil Health. For more intimate knowledge and understanding, turn to Fundamentals of Soil Science by Henry D. Foth and Lloyd M. Turk, or, much more deeply intimate, The Nature and Properties of Soils by Ray R. Weil and Nyle C. Brady. And then Lazy-Ass Gardening: Maximize Your Soil, Minimize Your Toil by Robert Kourik and — I almost forgot to mention! — Weedless Gardening by yours truly.

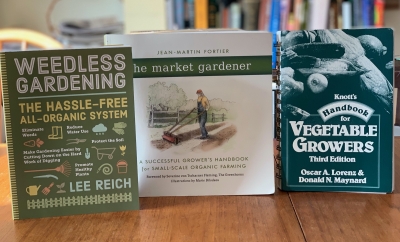

With the ground covered, vegetable can be planted. For oodles of very useful, basic information in the form of tables, there’s Knott’s Handbook for Vegetable Growers. It’s mostly for farmers, but also very useful for gardeners, as is The Market Gardener by J. M. Fortin. Also, again, my book Weedless Gardening.

Even here in New York’s Hudson Valley, where winter lows commonly plummet to minus 20°F, fresh, home-grown vegetables are possible. Elliot Coleman has explored and innovated many of the ways in Four-Season Harvest and The Winter Harvest Handbook. My greenhouse is currently packed with living, fresh greenery, growing slowly and ready for harvest now and over the next few months. If I had read Lindsey Schiller and Marc Plinke’s The Year Round Solar Greenhouse before building mine, I would have made it even more efficient as far as heat production and retention.

One can’t live on bread alone. For sprucing up appearances, good books include The American Meadow Garden by John Greenlee and, indoors, Well-Clad Windowsills by Tovah Martin. For solid, good information on trees, shrubs, and vines, I turn to my dog-eared copy of Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs. For flowers, The Flower Farmer by Lynn Byczynski.

Of course, no need to choose between living on bread alone or prettiness. You can often have both — on the same plant. That was the theme of Rosalind Creasy’s Edible Landscaping, which covered all kinds of plants from asparagus to wheat, as well as my more focused in its scope Landscaping with Fruit, going from alpine strawberries to wintergreen. Integrating edible plants in the landscape is an important component of permaculture; for a fun and short but thorough overview of the too often too seriously presented theory and practice of permaculture, I’d turn to Edible Landscaping with a Permaculture Twist by Michael Judd.

AND ROUNDING THEM OUT . . .

Many of the books on my shelves are of a more general nature. Early on in my gardening life, I frequently dipped into them; not so much these days. Still, my keeping them on the shelves is evidence of their value to me.

One of the best for a broad overview of everything from garden history, design, botany (and much more) is Hugh Johnson’s Principles of Gardening. Also painting a broad stroke but more on the nitty gritty of what to so when, and how to do it in the garden, through the year is my A Northeast Gardener’s Year (my first book, back in 199!) and Roy Biles The Complete Book of Garden Magic. The latter was published in 1951, so take some of the recommendations, especially those for pesticides with a grain of salt. But you’ll know to do that that after poring through all the other books I mentioned.

The End

/11 Comments/in Vegetables/by Lee ReichSnow Day

On December 2nd, my gardening season officially ended. It was brought to a screeching halt as a foot of heavy, white powder descended to democratically blanket my meadow, my vegetable beds, my terraces, and my deck.

I have to admit that it was welcome as I had spent the previous few weeks furiously getting ready for the end. Compost now covers most of the vegetable beds. Wood chips and neighbors’ raked leaves lie thickly beneath berry bushes and recently planted Korean pine (for nuts), chestnut, and pear trees.

Left in place, the one tunnel protecting a bed in the vegetable garden would have been collapsed by a heavy snow; I dismantled it. This tunnel consisted of metal hoops, 4 feet apart, each 5 feet long with either end pushed into the ground at each edge of the bed. The row of hoops was covered with vented, clear plastic and then, for added cold protection, a layer of “row cover” (a diaphanous fabric that lets air, water, and some light penetrate while affording a few additional degrees of cold protection).

I secured the clear plastic and the row cover layers by “planting” another metal hoop over them, right where the first hoops were”planted.” This setup makes it easy to slide the layers up and down, as needed, to reach in for harvest.

After dismantling the hoops and coverings, I picked over what remained. Cold had turned the few heads of lettuce left in the tunnel to mush. Surprisingly, a few small heads of pac choi (the varieties Joi Choi and Prize Choi) and large heads of napa type Chinese cabbage (the variety Blues) were in pretty much perfect condition.

My surprise came about because I had checked my minimum-maximum thermometer which registered the minimum temperature this fall as having dipped as low as 11° Fahrenheit. That’s very good protection from a thin layer of clear plastic topped by a layer of row cover — coupled with what are evidently quite cold-hardy varieties of Chinese cabbage.

Cloche History

Cold protection has come a long way since I started gardening. Over the years, cold protection devices, commercial and home-made, have undergone various incarnations in my gardens. Early on, with a bow to traditional cloches, I cut bottoms off gallon glass jugs for mini-greenhouses over individual or groups of very small plants.

(Cloche, pronounced klōsh, is the French word for “bell.” The original cloches were large bell-shaped jars that 19th-century French market gardeners placed over plants in spring and fall to act as portable miniature greenhouses. At one time, these glass jars covered acres of fields outside Paris that supplied out-of-season vegetables to the city’s households and restaurants.)

The classic glass bell jars are still available but have some significant limitations. Because they’re made from heavy glass and are small, the air trapped within can quickly get too hot on sunny days, cooking plants. And close attention needs to be paid to ventilation. A professional gardening friend, trained many years in France, tells of trudging out to cloche-covered fields on bright, frosty mornings to slide a block of wood under one side of each cloche to vent it during sunny days. In late afternoon he’d walk the field kicking out the blocks, setting each cloche flat on the ground to seal the warm air in for the night.

Although modern versions of these individual cloches are not as elegant as the traditional glass bell jars, some offer the same or a better degree of frost protection, are made of lightweight materials, are easier to vent, and are more convenient to store.

Modern variations on the cloche include: Clear umbrellas, which fold and unfold for easy storage, with spike handles that hold them in place; lightweight, durable, and inexpensive plastic versions of the traditional glass jar cloche; plastic milk jugs with the bottoms cut and vented by opening the lid; waxed-paper Hot Kaps. These vary in the degree of cold protection they offer as well as the size of the area they protect.

Tunnel type cloches protect whole rows or beds of plants. My original tunnel cloches were ersatz, British-made Chase cloches, which cleverly held glass panes into a ventable barn shape. Placed end to end, they created a tunnel, mini-greenhouse. I originally made my own from straightened coat hangar wire, then got hold of the real thing.

Chase cloches

Problem was, I discovered, that they work best in climates where temperatures are moderated, such as in northern Europe or near large bodies of water. (Anybody in those locations want some Chase cloche wires?)

So I graduated to the much more effective but much less attractive tunnel cloches, or “tunnels,” I described above.