APICAL DOMINANCE — WHAT FUN!

Suppression & Stimulation

“Apical dominance” sounds sadomasochistic, but no reason to shudder: it’s practiced by plants and, even when carried to an extreme, results in something as agreeable as a head of cabbage. True, we gardeners sometimes have a hand in apical dominance, but it’s still just good, clean fun.

Look upon it as hormones gone awry or as hormones doing what they’re supposed to do; either way, apical dominance is the result of a hormone, called auxin (AWK-sin), that is produced in the tips of growing shoots or at the high point of stems. Traveling down inside the stem, auxin sets off a chain of reactions that puts the brakes, to some degree, on growth of side shoots, giving the uppermost growing point (the apical point) of any stem the upper hand in growth.

Side shoots mostly arise from buds along a stem, and whether or not a bud grows out into a shoot depends on how close the bud is to the source of auxin; the closer to the source, the greater the inhibition, how far and to what degree depend on the genetics of the plant. ‘Mammoth Russian’ is a variety of sunflower that grows just as a single stem capped by a large flowering disk; with no side branches at all, this variety demonstrates an extreme example of apical dominance.  At the other extreme would be one of the shrubby species of willows that keeps sprouting side branches freely all along their growing shoots.

At the other extreme would be one of the shrubby species of willows that keeps sprouting side branches freely all along their growing shoots.

Even within a single species of plants, individuals vary in their tendency to express apical dominance. A fuchsia variety such as ‘Beacon Delight’ expresses strong apical dominance, so is easier to train upright into a miniature tree (“a standard”) than is a trailing variety such as ‘Basket Girl’, which has weak apical dominance. Only with the help of a stake and diligent pruning of side branches can ‘Basket Girl’ be coaxed to take on the shape of a miniature tree.

(This post is excerpted from my books The Ever Curious Gardener and The Pruning Book.)

Some Pinching

There are times when I want to thwart apical dominance: to get a stem to grow side branches, for instance. One way to do this is by removing the source of auxin — by pruning. The effect is only temporary because a new, uppermost bud soon establishes itself as apically dominant.

For the least possible pruning, I’ll just pinch out the soft growing point of a shoot with my thumbnail. This quick and simple check to auxin flow not only causes growth to falter briefly, but also causes lateral buds that were dormant to be awakened into growth. I pinch back the main shoot of coleus plants to make them grow bushier, which happens coincidentally when I harvest basil.

Another reason I pinch out a shoot tip is to slow growth. For example, I pinch out the tips of side branches of my young apple tree that turn upward and threaten the dominance of the single leading shoot (the “central leader”) that I‘ve selected for the growing young tree.

Repeated pinching make a rosemary standard. (Photo from THE PRUNING BOOK)

Whether done by me, you, insects, or diseases, plant response to pinching is relatively quick. Experiments with pea seedlings show that lower buds are stirred into activity in as little as four hours after the apical bud is removed.

And More Dramatic Cuts

Cutting back a larger portion of stem differs from pinching in the degree of response. The more drastically a stem is cut back, the fewer side shoots awaken, but the more vigorously each side shoot grows. This type of cut is called a “heading cut.”

V. H. Arlein, from THE EVER CURIOUS GARDENER

The more inherently vigorous a young stem is before it is headed back, the more vigorous the response to such pruning. Inherent vigor is greater the more vertically-oriented a stem, and the younger it is.

I have a long privet hedge that needs to be sheared every few weeks through summer to keep it to the shape and size I want. Shearing the hedge is, essentially, making hundreds — thousands? — of slight heading cuts. Plants respond just the way I hope, with dense growth of many short shoots.

At the other extreme is how I prune my butterfly bush. Lopping the bush’s stems almost back to ground level late each winter is how to coax forth a few of each summer’s long, graceful, flowering stems.

On fruit trees, my pruning cuts vary in severity, with the goal of coaxing some — but not too much — new growth on which to bear fruit to replace decrepit older growth. The degree depends on the kind of fruit tree. The apple trees and pear trees, for instance, get a relatively light pruning because they bear well on branches even a decade old.

Old wood bears pear flower buds

A peach tree needs more aggressive pruning to stimulate plenty of new shoots, which are the ones bearing next season’s fruits.

Peach blossoms on young stems

Thinning

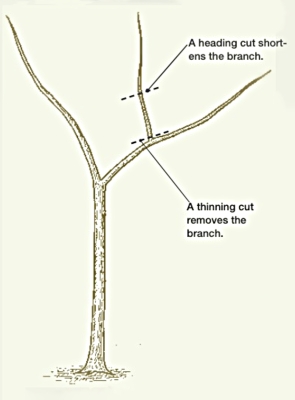

Heading vs. thinning cut. V.H. Arlein from THE PRUNING BOOK

Many a homeowner deals with an overgrown tree — one that has grown to block a window, for example — by irreverently hacking back the tops of branches that are blocking that window. Said homeowner then bemoans the dense and vigorous sprouts that regrow and quickly block that window again. More effective would be “thinning cuts,” which are cuts that totally remove offending branches right to their origin. With no buds left to regrow, apical dominance is then moot. Plant response is: nothing, nada, zip — near the cut, at least.

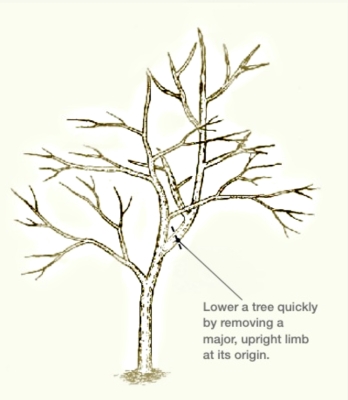

V.H. Arlein from THE PRUNING BOOK

I use thinning cuts for congestion (on my plants). When too many stems clog up the interior of a tree or shrub, removing some of them right to their origins opens up the space without eliciting regrowth at the cuts. For that aforementioned tree blocking a window: not only do thinning cuts not result in regrowth, but they also can be conveniently made closer to ground level, at the origins of the offending stems.

Sometimes It’s Better to Bend

Because auxin is produced at the highest point of a stem, an elegant way to thwart or re-direct apical dominance without having to prune off any part of a shoot is to bend it down. If the dampened stem is bent in an arch, a bud at or near the high point of the arch becomes top dog and sprouts to become, usually, the most vigorous shoot.

On the other hand, if a stem is lowered while being kept straight, that is, without creating an arch, then each bud along the stem is only incrementally higher than the one before it. In this case, the uppermost bud expresses weak apical dominance and many buds lower down along the stem are released from inhibition to make relatively weak growth.

The more vertically oriented the shoot, the fewer buds awaken and the more growth from each bud, especially those nearer the tip of the stem. The more horizontal the branch, the more buds awaken and the less growth from each. So I can regulate the amount of growth and side-branching with appropriate adjustment of branch angle, changing it, if necessary, as I watch my plant grow.

And this is the coolest part: There’s a push and pull within any plant between growing shoots and growing fruits. A more horizontal stem puts less energy into shoot growth, so tends to make more flowers and fruits. So playing with branch orientation is a way to regulate fruit production in fruit trees. Along with beauty when they’re trained as espaliers.

Espalier pear tree

A couple of other “pruners” we have here in our orchard and berry patches are the deer and the porcupine es. After they are done “pruning” (usually early winter and then very early spring), i assess the job they did and continue with my pruning in the spring.

Thanks, Lee, for widening my knowledge of pruning. This past winter and spring were just plain horrible due to polar blasts and very late May freezes. Then an onslaught of rain all summer and cool temps. No peaches, very few apples , a handful of grapes. They all look well now and I will gently tackle t.he pruning this spring, hoping the trees, vines and bushes have recuperated enough from the past three seasons. We live on western slopes of the Green Mts in central VT.

Yes, very poor weather last season here too. But at least no tornadoes or earthquakes around here, and usually no severe flooding. Western slopes of Green Mt.: beautiful area with which I’m very familiar.

I can identify with Pauline regarding pruning by wildlife. In S.E. Alaska we have brown bears and moose that help with the pruning on my espalier apple trees and my sour cherry trees.

Your pruning book is on my bookshelf and well used.

That doesn’t sound live very detailed, fine pruning. But if it works . . .

Glad you like my pruning book. I enjoyed traveling to Alaska and giving some talks there back in 2008, thanks to arrangements by my buddy Jeff Lowenfels.