HOT OFF THE PRESS

A New Map

The coldest nights of the year are due to arrive in about a month. These frigid nights might test the hardiness of trees, vines, and shrubs, perhaps nipping back a few branches here or there on some plants, perhaps killing others outright. Though bitter cold is a few weeks away, I have done what I could to prepare plants for the onslaught.

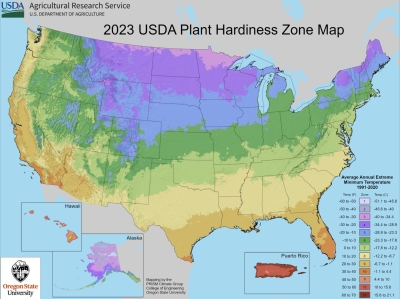

The first step in preparing any plant for the winter is knowing how cold it’s going to get. There’s no crystal ball offering this information, but decades of weather data have been compiled by the U. S. Department of Agriculture to prepare the USDA Hardiness Zone Map, which is helpful in predicting the probable minimum temperature for an area. The map has gone through numerous incarnations of increasing accuracy and . . . drum roll . . . recently this year the latest incarnation was revealed.

So, what’s new? The increasing accuracy reflects minimum temperatures measured at 13,625 weather stations averaged over 30 years. As before the country is divided into zones denoted by color and number, 13 of them, the lower numbers reflecting colder regions. Each zone denotes the average coldest temperature in that time period, not the minimum temperature ever experienced.

You often see this map, the country covered over my squiggly lines filled in with a color. Big change this year: The USDA offers this map only online (https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/), which, even for those of us who like to view hard copies, does have its benefits. For one, you can just plug in your zip code and the map will zoom to your site, from which you can, of course, zoom in and out and “travel” around. The increasing detail shows up, for instance, in the “heat islands” created by the abundance of concrete in urban centers.

(Similar hardiness zone maps have been created for Mexico, Canada, and Europe.)

Also Consider…

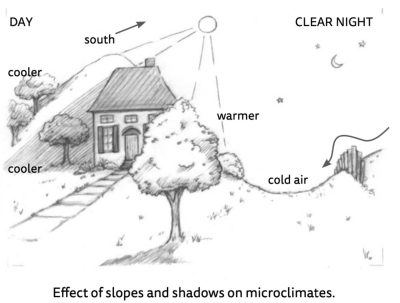

As helpful as the map is, take it with some grains of salt, for a number of reasons. For one, it doesn’t take into account microclimate, that is, small pockets where air and soil temperatures are either colder or warmer than the general climate, perhaps even different enough to represent a shift to the next higher or lower climate zone. I have a brick house, and winter aconites and anemones planted near any south wall always sprout earlier there than in places further away, the effect from the retention and radiation of warmth from that sun-warmed wall.

At your home, a stone wall or a fence might create a little “heat island.” Wind also plays a role.

Lingering snow on north side of building

Ground that has been warmed by day is radiated skyward at night unless blocked by clouds or trees. So the air rapidly cools as the sun sets on cool clear nights. Cold air is heavier than warm air, so it flows down slopes like water to settles into low-lying areas — like my farmden, here in the Wallkill River valley! I’ve even felt that difference riding my bicycle on a clear summer night when the air gets a further slight chill from the dip in the road right near my home.

Illustration by VH Arlein, from my book The Ever Curious Gardener

Except under these conditions of cool, clear nights, higher elevations generally are colder by 6°F for every 1000 feet than lower elevations.

The new map has officially upgraded my farmden from Zone 5b (minimum of -15 to -10°F) to Zone 6a (minimum of -5 to 0°F). Even if experience tells me that the USDA is a half a zone too warm right here, it’s getting downright tropical. Thirty years ago, winter lows were reliably -20°F. I see those warmer temperatures reflected in the borderline hardy plants — bamboo, tender roses, lavender, and crocosmia, for example — that used to suffer, if they even survived through winter.

Crocosmia

And the Plants

It’s not only a plant’s innate cold-hardiness that predicts how it emerges from winter’s cold. A humid climate increases a plants tolerance. A borderline hardy plant that needs full sunlight will suffer winter’s blow if grown in shade.

Snow can insulate a plant from cold, either by covering the whole plant, or, in the case of herbaceous perennials or low-growing woody plants, by just covering the ground to insulate the roots.

Lingonberry emerging from snow cover

These days, here at least, I can’t rely on snow cover making it’s appearance, so I substitute autumn leaves or straw.

If I want to provide further protection, I wrap a plant in an overcoat of burlap or straw. When I lived in Maryland, I did this for my figs, which stayed outdoors all winter. (That was decades ago when winters were colder and it was necessary there.)

Figs protected for winter, from Growing Figs in Cold Climates

I also went to that trouble here for special plants like my hardy kiwis and raisin trees (Hovenia dulcis), because they were special and because they needed this protection only when young. I leave my tender roses unprotected in a Darwinian selection of survival of the fittest.

Besides plant and site selection, I do all I can in late summer and early autumn to slow plant growth, so that plants are physiologically toughening up for winter. “Doing,” in this case means “not doing” — no pruning, no fertilizing, no watering, or anything else that would stimulate growth.

Let’s be very clear: The change in Cold Hardiness Zones, as well as some records and observations I’ve made over the past 40 years, are indications of global warming. That warming is already bringing heat waves, floods, storms, wildfires, and droughts of biblical proportions worldwide, even if in your garden or my garden the effect might be welcome. I’m hoping I won’t ever be able to grow camellias, crape myrtles, and gardenias outdoors, even though I’d like to. And action is needed more than just hope.

“What he said” about global warming.