HOW ABOUT THOSE OLD SEED PACKETS?

It’s wasted effort to sprinkle dead seeds into furrows either in the garden or seed flats. Seeds are living, albeit dormant, embryonic plants which do not live forever.

When you buy a packet of seeds, you’re assured of their viability. Government standards set the minimum percentage of seeds that must germinate for each type of seed. The packing date and the germination percentage often are stamped on the packet. (The germination percentage must be indicated only if it is below standard.) I write the year on any seed packets on which the date is not stamped.

Your old, dog-eared seed packets may or may not be worth using this season. It depends on where the packets were kept and the types of seeds they contain. Last year I got tired of trying to decide how well my seeds were stored and which were still worth sowing; I took action.

Anti-Aging Treatments

Conditions that slow biological and chemical reactions also slow aging of seeds, i.e. low temperature, low humidity, and low oxygen. In years past, I’ve stored seeds in canning jars in my freezer, then moved the jars to the refrigerator as the freezer filled in fall. Powdered milk sprinkled into the bottom of the jars maintained low humidity. (Or so I assumed.) But all those jars took up lots of space, especially as my seed collections grew, and seed packets don’t pack well into canning jars.

As far as low oxygen storage, it’s not practical for most of us. I did try, one year, to create low oxygen seed storage by reversing gaskets and putting a one way valve on a bicycle pump.  This allowed me to draw some of the air out of the jars with a tube connecting the pump to a ‘FoodSaver Wide-Mouth Jar Sealer.’ It did (usually) create somewhat of a vacuum but it was too much trouble to get at the seeds and re-seal a jar each time. And, again, seed packets don’t pack well into canning jars.

This allowed me to draw some of the air out of the jars with a tube connecting the pump to a ‘FoodSaver Wide-Mouth Jar Sealer.’ It did (usually) create somewhat of a vacuum but it was too much trouble to get at the seeds and re-seal a jar each time. And, again, seed packets don’t pack well into canning jars.

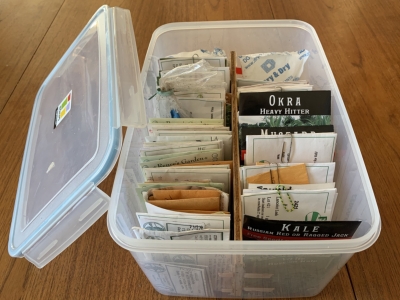

So last year I came up with a figurative “better mousetrap.” After much searching for a plastic, freezer-safe, air-tight, leak-proof, reasonably-sized tub for the bulk of my seeds — a stout order, all this — I came upon the ‘Komax Biokips 35-Cup Large Food Storage Container.’ Perfect!

I measured, cut, and hot-glued a piece of 1/4-inch plywood to run up the center of the tub to allow for two rows of seed packet. A couple of 100 gram silica gel packets in the tub at the end of each row keeps humidity low. The packets are easily rejuvenated in a warm oven for 20 minutes. I just measured the humidity in the tub (I like to measure); it’s a dry 17%.

Moving the tub into the relative coolness of my basement in summer should maintain conditions in line with the guideline for seed storage that Fahrenheit temperature plus relative humidity should total less than 100. Come cooler weather in fall and then cold weather in winter, back the the tub goes to a shelf in my unheated workshop.

Worth Saving?

Seeds differ in how long they remain viable. Even with the best storage conditions, it’s not worth the risk to sow parsnip or salsify seeds after they are more than one year old. Two years of sowings can be expected from packets of carrot, onion, and sweet corn seed; three years from peas and beans, peppers, radishes, and beets; and four or five years from cabbage, broccoli, brussels sprouts, cucumbers, melons, and lettuce.

Among flower seeds, the shortest-lived are delphiniums, aster, candytuft, and phlox. Packets of alyssum, Shasta daisy, calendula, sweet peas, poppies, and marigold can be re-used for five or ten years before their seeds get too old.

In a frugal mood, I might do a germination test to definitively measure whether an old seed packet is worth saving. Counting out at least 20 seeds from each packet to be tested, I spread the seeds between two moist paper towels on a plate. Inverting another plate over the first plate seals in moisture and then the whole setup goes where the temperature is warm, around 75 degrees. After one to two weeks, I peel apart the paper towels and count the number of seeds with little white root “tails”.

I figure the percentage, and if it’s low, the seed packet gets tossed into the compost pile (not given away!). Or, I might use the seed and adjust my sowing rate accordingly.

And the Record Is . . .

Among the shortest-lived seeds are those of alpine plants; their viability might plummet after only a couple of weeks.

As far as longest-lived seeds, there’s the story of the 10,000 year old lupine seed that germinated after being taken out of a lemming burrow in the Yukon permafrost. Alas, it’s only a story, one debunked by radiocarbon dating.

The true record for seed longevity was, until recently, 2,000 years, and was held by a date palm grown from seed recovered from an ancient fortress in Israel.

No one knows exactly what happens within a seed to make it lose its viability. Besides lack of germination, old seeds undergo a slight change of color, lose their lustre, and show decreased resistance to fungal infections. There’s more leakage of substances from dead seeds than from young, fresh seeds, so perhaps aging influences the integrity of the cell membranes. Or, since old seeds are less metabolically active than young seeds, the old seeds leak metabolites that they cannot use.

(The above was adapted from my book The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden available from the usual sources and, signed, from me.)

“Maple decline” is a disease complex brought on by some combination of drought, soil compaction, road salt, root damage, and air pollution. Upper branches are usually the first to go, and once decline begins, secondary fungi and insects speed the process along.

“Maple decline” is a disease complex brought on by some combination of drought, soil compaction, road salt, root damage, and air pollution. Upper branches are usually the first to go, and once decline begins, secondary fungi and insects speed the process along.

The one on my garden gate is especially useful in spring and fall, when frosts threaten. As soon as the snow melts, my third

The one on my garden gate is especially useful in spring and fall, when frosts threaten. As soon as the snow melts, my third