MY VINES GET IN ORDER

Pruning vs. Training?

A long time ago, when I first started growing fruit trees and vines, I read a lot about the all-important pruning and training they require. But I couldn’t get clear on my head what exactly the difference was between “pruning” and “training.” I went on to learn that and a whole lot more about pruning (through books, as an ag researcher for Cornell University, and with practical experience), and eventually wrote my own book about pruning, hoping to present the techniques with more clarity and completeness than all the books I had read. Perhaps my book, The Pruning Book, does that.

Okay, to answer my question of yore. “Training” is developing the young plant to a permanent framework that is sturdy and will always have its limbs bathed in light and air, and whose fruits hang within easy reach.

Kiwifruit within easy reach

Training involves some pruning as well as coaxing stems to grow in certain directions. Once a fruit tree or vine’s training period ends, it generally only needs annual pruning.

Vine-y Training

I thought of all this today as I pruned hardy kiwifruit and grape vines. Both fruiting vines have been trained and are pruned similarly, with one slight variation that I’ll soon mention.

The kiwi and grape vines are trained as “double cordons” which are permanent arms sitting atop a trunk. They run in opposite directions along the middle wire of a 5-wire trellis, the wires parallel and supported about 6 feet of the ground on the cross-arms of T-posts. Each young vine was planted next to a metal or wooden stake to which the plant’s most vigorous stem was tied.

Once that trunk-to-be reached up to the middle wire, I tied it there and cut off all other stems. That trunk-to-be does, of course, keep growing; that new growth gets bent over and tied along the middle wire. Bending coaxes new buds to burst just beneath the bend, one of which is also bent over and trained along the middle wire in opposite direction to the first stem. Both these horizontal stems became the cordons, permanent arms of the plant. Growing off at right angles to the cordons are the fruiting shoots which, weighed down with their weight of fruit, drape onto the other wires.

Vine Maintenance

Today I’m maintenance pruning vines whose training period ended years ago. Maintenance pruning a mature fruiting vine keeps it bearing high quality fruit within easy reach year after year, all accomplished with a renewal method. That is, except for the trunk and the cordon, the vine is completely renewed with each year’s pruning.

I’ll admit it: A vine looks like a tangled mess before being pruned. But step by step, it begins to take shape and make sense.

Knowing how a plant bears fruit is important in maintenance pruning. Kiwi and grape vines bear on new shoots growing off one-year-old stems. Kiwis bear best if those one-year-old stems are about 18 inches long. Grape one-year-old stems can be left long or short, but for my method of training, I want each one about two buds long, which is just a few inches.

Fruiting grape shoots emerge from 1-yr-old stem

Step one is a no-brainer. The outermost wires are 4 feet apart so I lop all growth back to just beyond those wires. My tool of choice for this is a battery-powered hedge trimmer although pruning shears would also do the trick, except at a snail’s pace.

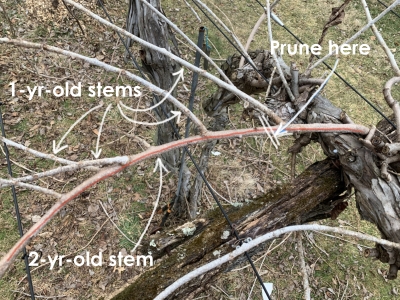

Step two is to remove excess growth, which does two things. It removes potential fruits so that more of the plant’s flavor-rich goodness gets funneled into those that remain, and it decongests the plant. For this step, I cut back all stems 2 years or older.

But wait! Two-year-old stems have one-year-old stems, the stems needed for bearing shoots, growing off of them. So rather than cut a two-year-old stem all the way back to its cordon, I cut it back to a one-year-old stem originating near the cordon. Some one-year-old stems also grow right from the cordon. The best one-year-old stems are those that are moderately vigorous and, of course, look healthy. Moderately vigorous stems, for grape or kiwi, are about pencil thick (if you can remember what a pencil looks like; if not, about 1/4” thick).

Kiwi stem and pruning detail

There will always be too many one-year-old stems for the plant to make tasty fruit. So I reduce the number of potential fruits by removing some of the one-year-old stems, enough to leave six to ten inches between them on each side of a cordon.

Pruned grape vine

Not finished yet. The final step is to shorten the fruiting shoots. For hardy kiwis, I cut them back to 18 to 24 inches long. For grapes, to about 2 buds or a few inches long.

Oh, one more thing to do: I prune off any new growth rising up from ground level or along the trunk lower than the cordons.

And one more thing: I step back to admire my handiwork. (Here is a video of me pruning a kiwi vine.)

But What About Bushes?

You might have noticed, early on, that I wrote about pruning and training “fruit trees and vines.” What about blueberries, currants, gooseberries, elderberries, and other FRUITING BUSHES. Yes, they need annual pruning also. No, they do not need training. Although the plants are perennial, their stems are evanescent, all with a limited life. They are pruned by a renewal method — at ground level. All this and much, much more (pruning ornamental plants, houseplants; creating and caring for an espalier; how to scythe; etc) in The Pruning Book, of course.