PLANT STRAWBERRY PLANT(S)

Humble Appearing Beginnings

The UPS man’s face is a familiar one this time of year, as he brings me boxes and bags of plants from all around the country. I can’t count how many times I’ve met his brisk walk up the driveway to retrieve a box of strawberry plants. A strawberry bed languishes after a few years, typically five years, and when that happens, I just choose a new site and order new plants.

Epsey strawberry, painted in 1911

I begin again with new plants, because although strawberries are perennial plants, old plantings eventually pick up diseases from wild strawberries and related plants. By planting a new bed the year before the old one is due to expire, there’s no break in enjoying fresh strawberries every June.

Opening the box of strawberry plants just arrived provides a sorry sight to the eyes: twenty-five plants, leafless or nearly leafless, bound with a rubber band into a package small enough to hold in my fist. But I take heart; the plants are dormant and, given warmth and soil, will come to life. Immediately as I say good-bye to the UPS guy I open the plastic bag to make sure there’s some moisture within. If not, I add some and reseal the bag. In either case I put the bag in the refrigerator until I’m ready to plant.

Planting Location and Design

Let’s hold off planting a minute and see what type of site I choose for my strawberry beds. The plants thrive best with full sun (at least 6 hours per day with Ol’ Sol beaming directly on the plants) and in a soil that is both well-drained and rich in organic matter. Anything less than the above and fruit flavor suffers and plants are more prone to disease.

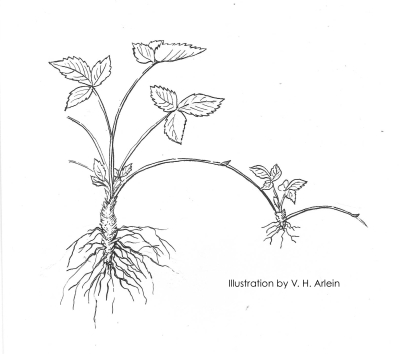

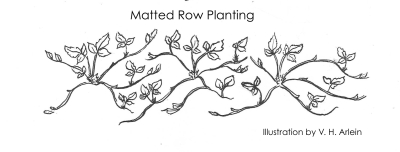

Strawberry plants spread by runners, which are stems that creep along the ground forming new plants at intervals along their length.  Eventually, plants in a strawberry bed should be 6 to 12 inches apart. The “matted row” system of strawberry planting makes full use of these runners. Plants are set far apart (4 feet between rows and 2 feet between plants) and the spaces between the plants fill in with runner plants which fruit the following season.

Eventually, plants in a strawberry bed should be 6 to 12 inches apart. The “matted row” system of strawberry planting makes full use of these runners. Plants are set far apart (4 feet between rows and 2 feet between plants) and the spaces between the plants fill in with runner plants which fruit the following season.  The matted row is allowed to fill in to a width of 2 feet, and all plants attempting to spread beyond that width are kept in bounds with a rototiller or by hand. With age, that 2 foot ribbon rapidly becomes overcrowded unless old plants are weeded out.

The matted row is allowed to fill in to a width of 2 feet, and all plants attempting to spread beyond that width are kept in bounds with a rototiller or by hand. With age, that 2 foot ribbon rapidly becomes overcrowded unless old plants are weeded out.

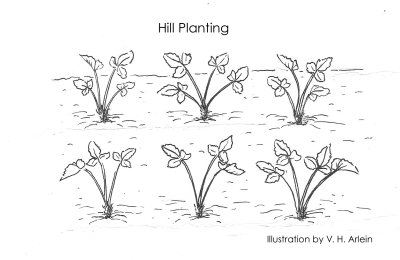

I prefer the opposite extreme in strawberry planting systems, the “hill” system, whereby plants are set in a double row with 12 inches between the rows and between plants in the row. (If there’s more than one double row, the next double row is 3 feet away.)  The hill system demands the somewhat tedious job of pinching off all runners through the summer, but the planting stays neater and yields the most berries the first bearing season.

The hill system demands the somewhat tedious job of pinching off all runners through the summer, but the planting stays neater and yields the most berries the first bearing season.

The “spaced plant” system splits the difference between the hill system and the matted row system. Plants are set moderately far apart, and only 4 or 5 daughter plants are allowed to take root, carefully spaced around each mother plant.

And Into the Ground They Go

Actual planting of strawberries in the ground takes little time if the soil is in good condition — weed-free, rich in humus, and not too dry and not too moist. Gently squeeze a handful; it should crumble.

I prepare the plants by retrieving them from the refrigerator, undoing the bundle, and trimming the roots back to three or four inches. Then I drop the plants into a shallow pan of water to keep them moist while I plant.

To plant, I thrust a trowel straight down into the soil, then pull the handle towards me enough to open up a slit for a plant.  With the roots fanned out by my other hand, the trimmed plant’s roots fit easily into the waiting slit. Planting is completed as I remove the trowel and firm soil against the roots with the heel of my hand.

With the roots fanned out by my other hand, the trimmed plant’s roots fit easily into the waiting slit. Planting is completed as I remove the trowel and firm soil against the roots with the heel of my hand.

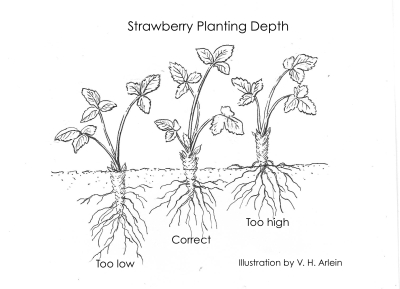

Planting depth is important. Set too shallow and the plants dry out, set too deeply and they suffocate. The ground line should go right through the middle of the crown, which is actually a stem that’s been telescoped down so that each leaf grows off it right next to the next leaf along the stem, rather than a few inches apart, as in most stems.

A number of years back I was helping my friend Helene plant her first strawberry bed. Sorry Helene, gotta write about it. My job was to open up the holes; your job was to plant. After a dozen holes, I glanced back over my shoulder to check your progress. You had listened carefully: each plant was set with the ground line through the middle of the crown, against which the soil was firmed, even lovingly smoothed. And, as I had instructed, you had neatly fanned out each plant’s roots. How did I know? Because the plants were upside down, with their roots splayed upward in the air!

First blueberries on heels of last strawberries