BEAUTY AND FLAVOR

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (in my opinion)

For better or worse, every year nurseries and seed companies send me a few plants or seeds to try out and perhaps write about. The “for better” part is that I get to grow a lot of worthwhile plants. The “for worse part” is that I have to grow some garden “dogs.” (I use the word “dogs” disparagingly, with apologies to Sammy and Daisy, my good and true canines.) Before my memory fades, let me jot down impressions of a quartet of low, mounded annuals that I trialed this year.

Calibrachoa Superbells Blackberry Punch was billed as heat and drought tolerant, which it was. As billed, it also was smothered in flowers all summer long. It’s a petunia relative and look-alike. Still, I give it thumbs down. But that’s just me; I don’t particularly like purple flowers, and especially those that are purple with dark purple centers.

I’ll have to give Verbena Superbena Royale Chambray a similar thumbs down.  It’s that purple again, light purple in this case. Also, the plants weren’t exactly smothered with flowers and most prominent, then, were the leaves which were not particularly attractive.

It’s that purple again, light purple in this case. Also, the plants weren’t exactly smothered with flowers and most prominent, then, were the leaves which were not particularly attractive.

Golddust (Mecardonia hybrid) made tight mounds of small yellow flowers nestled among small yellow leaves. I give this one a partial thumbs up. The flowers were too small and there weren’t enough of them even if the leaves alone did make pleasant, lime green mounds.

And finally, a rousing thumbs up for Goldilocks Rocks (Bidens ferulifolia). This plant also was a low mound of tiny leaves, needle-shaped this time. Sprinkled generously on top of the leaves all summer long were sunny yellow blooms, each about an inch across and resembling single marigolds. Flowering was nonstop, even up through the many recent frosts here, right down to 24° F.

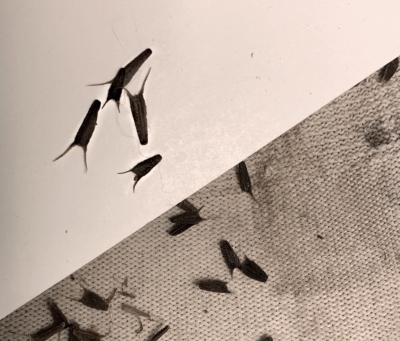

Bidens in its botanical name caused me slight pause when I planted Goldilocks, not because of any displeasure with our president, but because the common name for this genus is sticktight, or beggartick. You know those half-inch, flat, 2-pronged burrs that attach to animals — and, inconveniently, your socks — when you walk through wild meadows?  Those are Bidens, trying to spread. (Not to be confused with the round, marble-size burs of burdock.)

Those are Bidens, trying to spread. (Not to be confused with the round, marble-size burs of burdock.)

No problem with Goldilocks Rocks that lined my vegetable garden paths. The flowers were too low to reach any higher than my shoes.

Ugly, Beautiful, and Tasty

Despite the recent spate of cold temperatures, there’s still fruit out in the garden, hanging on and ready for picking at my leisure.

The first is medlar (Mespilus germanica), a fruit that was popular in the Middle Ages, but not now. Its unpopularity now is due mostly to its appearance. One writer described it as “a crabby-looking, brownish-green, truncated, little spheroid of unsympathetic appearance.” The fruits resemble small, russeted apples, tinged dull yellow or red, with their calyx ends (across from the stems) flared open. I happen to find that look attractive.

The harvested fruit needs to sit on a counter a few days, like pears, before it’s ready to eat. Worse, from a commercial standpoint these days, when ready to eat the firm, white flesh turns to brown mush. Yechhh! Except that it’s delicious, with a refreshing briskness and winy overtones, like old-fashioned applesauce laced with cinnamon.

The plant itself is quite beautiful, a small rustic-looking tree with elbowed limbs. In late spring individual white blossoms resembling wild roses festoon the branches. In autumn, medlar leaves turn warm, rich shades of yellow, orange, and russet.

I would bill medlar as very easy to grow, except here on the farmden. A few years ago, a pest started attacking my fruits, turning the flesh dry, rust-colored, and inedible. I have yet to identify this pest (rust?) which is absent just about everywhere else. Do any other of you few medlar growers have anything to say about this pest, if you’ve seen it?

Beautiful and Tasty

Walking around my home to the bed supported by a low, stone wall along my front walkway, we come to lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea). This fruit never fails to stir a smile, a dreamy look, perhaps even a tear in the eye of Scandinavians away from their native land. Nonetheless, it’s actually is native throughout the colder zones of the northern hemisphere.

Lingonberry is an evergreen groundcover growing only a few inches high; I grow it both for its beauty and its fruit. In spring the cutest little white, urn-shaped blossoms dangle upside down (upside down for an urn, that is) singly or in clusters near the ends of thin, semi-woody stems.  The bright red berries hang on the plants for a long time, well into winter, with their backdrop of holly-green, glossy leaves making a perfect holiday decoration in situ.

The bright red berries hang on the plants for a long time, well into winter, with their backdrop of holly-green, glossy leaves making a perfect holiday decoration in situ.

The key to success with lingonberries is suitable soil. Like blueberries, a close relative, they enjoy, they demand, a soil rich in organic matter, well aerated, consistently moist, and very acidic. I created these conditions with some peat moss in each planting hole, a year ‘round mulch of wood chips, leaves or sawdust, topped up annually, and sulfur applied to bring soil pH to between 4 and 5.5.

Lingonberries have been put to lots of culinary uses besides the usual lingonberry jam. I like to eat them straight from the plants. They’re not sweet, but they are delicious.

(I considered the two above-mentioned fruits so worthwhile that each warranted a chapter in my book Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden. This book’s out of print now, but is due to be revised and re-issued again in a couple of years. Some of the information in that book can be found in my currently available books Grow Fruit Naturally and Landscaping with Fruit.)

And, like the tropical species, flowers are followed by egg-shaped fruits filled with air and seeds around which clings a delectable gelatinous coating. You know the flavor if you’ve ever tasted Hawaiian punch.

And, like the tropical species, flowers are followed by egg-shaped fruits filled with air and seeds around which clings a delectable gelatinous coating. You know the flavor if you’ve ever tasted Hawaiian punch. It’s peak of popularity was in the Middle Ages. And though popular, it was made fun of for it’s appearance; Chaucer called it the “open-arse” fruit.

It’s peak of popularity was in the Middle Ages. And though popular, it was made fun of for it’s appearance; Chaucer called it the “open-arse” fruit.

Mostly I grow it for the novelty of an outdoor orange tree, for the sweetly fragrant blossoms, and for the decorative, green, swirling, recurved spiny stems.

Mostly I grow it for the novelty of an outdoor orange tree, for the sweetly fragrant blossoms, and for the decorative, green, swirling, recurved spiny stems.