COMPOST, FERTILITY, & SUSTAINABILITY

Compost and/or Living or Dead Organic Material = Sustainable Fertility

Maple leaves already dapple the ground in red and yellow (early this year), one morning showed off what was to come with frost on the windshield, and each day the sun each hangs lower in the sky, yet I’m getting ready for spring planting. Really! Yes, I’d rather do it now than in spring.

Beds of spent vegetables have been cleared. Okra plants, in this cool weather, just sat in place, hardly producing any new pods. So out went the plants. I severed the main roots with my hori-hori knife (www.oescoinc.com) and yanked out each stem. When corn is finished, it’s finished. Beds of early corn got replanted with endive, lettuce, and other late vegetables, but the latest beds of corn were harvested too late for replanting. Clearing away old vegetable plants not only clears the deck for next spring but also takes offsite some pests and diseases that might otherwise lurk around next year to do their evil work.

With spent vegetable plants cleared away — tomatoes and peppers are still yielding fruits, so they remain for now — I remove weeds. Ideally, all of them. Left in place, annual weeds spread seeds and roots of perennial weeds grab more tenaciously and deeper into the soil. A single pigweed plant, for instance, can drop 120,000 seeds, poised and ready to invade next year’s garden. That, and the 36,000 seeds on every plantain plant, the 39,000 seeds of each lamb’s-quarter plant, and the 8,000 seeds clustered in a crabgrass seedhead prompts me to pull these weeds now, before more seeds mature.

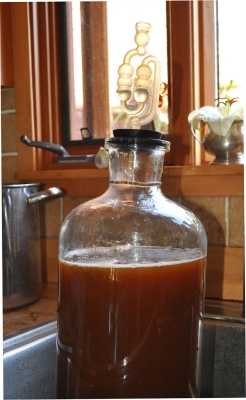

Of course, some weeds escape my notice, so the final step in preparation for spring is to suffocate these: I slather each planting bed with a one inch depth of mostly weed-free compost. A temporary 2X4 at each edge of the bed keeps the compost neatly in place until patted down firmly.

The compost does more than snuff out overlooked weeds. Its biotic life helps protect plants against pests and diseases. It helps soils hold water and air. And it feeds plants a smorgasbord of nutrients.

On a Garden, Farmden, or Small Farm, Fertility Simplified

Did I mention spreading fertilizer, “organic” or otherwise, in getting the soil ready for spring planting? No. A one-inch depth of compost supplies all the nutrients needed to grow vegetables, even in beds with closely spaced plants. Paraphrasing the Beatles lyrics, “All you need is . . .compost, da, da, da-da da.”

A garden is not Mother Nature left to her own devices; nonetheless, I try to emulate her as much as is practical. She does not spread fertilizer. Plants are naturally nourished as organic materials, such as leaves, stems, wood, roots, and dead animals, decompose to release whatever nutrients gave them life. I enjoy making compost and make enough to spread that required one-inch depth over all the beds.

Next best would be to spread some concentrated source of the most needed nutrients, that is, “fertilizer,” on the ground and supplement it with a mulch such as wood chips, straw, hay, or other organic material. Here, an organic fertilizer, such as soybean or alfalfa meal, has the advantage over a chemical fertilizer in that nutrients become available over a long time and are made so in response to temperature and moisture, in synch with plants’ needs.

Two advantages of maintaining fertility with compost rather than mulch plus fertilizer are that seeds are more easily planted directly in the compost and compost, if made from a variety of feedstuffs, provides a wider spectrum of nutrient for the plants.

Cover Crops, Used Correctly, for Even Large Farms

A wheat farmer in Montana is not going to be spreading an inch of compost on his 1,000 acres, or even soybean meal and a mulch of straw. Agriculture is a balancing act, again, not Mother Nature but not disrespecting her either. In the case of a wheat farmer, or any large scale farm, cover crops are a practical route to healthy soil.

Cover crops are plants grown specifically to maintain or improve a soil. Cover crops may occupy the ground for part or for the whole season. As they grow, their roots push through the soil to break it up and, upon their death, leave channels for air and water. Roots exude natural compounds that stimulate a a wide population of beneficial microbes and release nutrients from the soil’s rocky matrix. Leguminous cover crops garner nitrogen from the air into a form that plants can gobble up. And once dead, deliberately or with age, cover crops can maintain or increase all important soil organic matter.

The devil is in the details. Killed too young, while still lush and green, a cover crop adds nothing in the way of soil organic matter (but does protect the soil surface from erosion). Tilling a cover crop into the soil, a common practice, might burn up more organic matter, by giving the ground a big burst of oxygen, than is added by the cover crop, whether the cover crop is young or old. And then there is the choice of cover crop itself for regional adaptability, for shading out weeds, or for beefing up a poor soil.

How about this? Set aside a separate area for cover cropping each year. Or set aside a separate area for cover cropping, but mow the plants one or more times through the growing season to provide mulch or feedstuff for compost. With enough land and suitable mix of cover crops, including legumes for nitrogen.

—————————————-

“Sustainability” is a buzzword these days. Nourishing the ground with nothing more than annual sprinklings of chemical fertilizer not sustainable in terms of long-term soil health and because synthetic fertilizers require fossil fuels in their making. At he other end of the scale, primitive slash and burn agriculture, where land is cleared and burned, crops planted for a few years, then the site abandoned for a new site, is sustainable. But you need enough land to be able to leave time for the soil to naturally regenerate before another slashing and burning. In our “advanced” culture, recycling organic materials back to the land is also sustainable. It’s just a matter of getting the materials back into the soil, as compost or more directly, but not to a landfill or an ethanol (gasahol) factory.