Increasing My Hyacinthal Holdings

Hyacinth City

I’ve admitted this before; here’s more evidence of my addiction — to propagating plants. I currently have a seed flat that’s only 4 by 6 inches in size and is home to about 50 hyacinth plants. Obviously, the plants are small. But small and sturdy.

The genesis of all these plants goes back a couple of years when I needed photos for my book The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden. For the chapter on some aspects of the science of plant propagation and the practical application of that science, I made photos of some methods of multiplying hyacinth bulbs. Here’s an excerpt of that section:

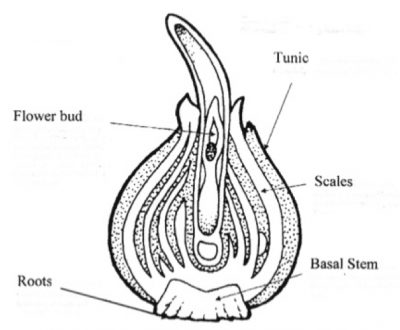

“Knowing what a bulb really is makes it easier to understand how they can multiply so prolifically that their flowering suffers, and how to get them to multiply for our benefit. Dig up a tulip or daffodil and slice it through the middle from the tip to the base. What you see is a series of fleshy scales, which are modified leaves, attached at their bases to a basal plate, off of which grow roots—just like an onion (but, in the case of daffodil, poisonous!). The scales store food for the bulb while it is dormant.

“Knowing what a bulb really is makes it easier to understand how they can multiply so prolifically that their flowering suffers, and how to get them to multiply for our benefit. Dig up a tulip or daffodil and slice it through the middle from the tip to the base. What you see is a series of fleshy scales, which are modified leaves, attached at their bases to a basal plate, off of which grow roots—just like an onion (but, in the case of daffodil, poisonous!). The scales store food for the bulb while it is dormant.

That bottom plate is the actual stem of the plant, a stem that has been telescoped down so that it’s only about a half-inch long. Those fleshy scales are what store food for the bulb, and, depending on the kind of bulb, are nothing more than modified leaves or the thickened bases of leaves.

Look at where the leaves meet the stems of a tomato vine, a maple tree—any plant, in fact—and you will notice that a bud develops just above that meeting point. Buds likewise develop in a bulb where each fleshy scale meets the stem, which is that bottom plate. On a tomato vine, buds can grow to become shoots; on a bulb, buds can grow to become small bulbs, called bulblets. In time, a bulblet graduates to become a full-fledged bulb that is large enough to flower.”

Look at where the leaves meet the stems of a tomato vine, a maple tree—any plant, in fact—and you will notice that a bud develops just above that meeting point. Buds likewise develop in a bulb where each fleshy scale meets the stem, which is that bottom plate. On a tomato vine, buds can grow to become shoots; on a bulb, buds can grow to become small bulbs, called bulblets. In time, a bulblet graduates to become a full-fledged bulb that is large enough to flower.”

Natural Increase

“Let’s see just how the big three flowering bulbs—tulips, daffodils, and hyacinths—grow. With tulips, the main bulb, the one that flowers, disintegrates right after flowering and is replaced by a cluster of new bulblets or bulbs. The mother bulb of a daffodil continues to grow after flowering, at the same time producing offsets of bulbs or bulblets which may remain attached to the mother bulb. Hyacinths grow the same way as daffodils, except for being much more reluctant to make babies.

All those bulblets and bulbs can, in time, crowd each other for light, food, and water, so flowering suffers. When my daffodils, tulips, or hyacinths seem to be making too many leaves and too few flowers, I know it’s time to dig them up and separate all the bulbs and bulblets. The best time for this operation is just as the foliage is dying back in spring or early summer because after that plants are out of sight until the following spring. Replanting can be done immediately or delayed until autumn.”

The Scoop on Propagating Bulbs

“Knowing something about bulb structure also gives me inside information on how to multiply my holdings faster, perhaps to make enough plants for a whole field or a giant flower bed. Merely digging up and planting offsets is one way of doing this. Also, knowing that the bottom plate is a stem and that the offsets come from side buds lets me coax those side buds to grow just as can be done with any other stem.

Pinching out the growing tip of any stem makes side buds grow. One way you get rid of, or ‘pinch out,’ the growing tip of a bulb is to turn the bulb upside down, then scoop out the center of the bottom plate with a spoon or knife.  Another way is to score the bottom plate with a knife into 6 pie shaped wedges, making each score cut deep enough to hit that growing point.

Another way is to score the bottom plate with a knife into 6 pie shaped wedges, making each score cut deep enough to hit that growing point.  After scoring or scooping, set the bulb in a warm place in dry sand or soil for planting outdoors in a nursery bed in autumn.

After scoring or scooping, set the bulb in a warm place in dry sand or soil for planting outdoors in a nursery bed in autumn. After a year, as many as 60 bulblets might be sprouting from the base of each scooped or scored bulb. Each bulblet does take 4 or 5 years to reach flowering size, but no matter. To quote an old Chinese saying: ‘The longest journey begins with the first step.’”

After a year, as many as 60 bulblets might be sprouting from the base of each scooped or scored bulb. Each bulblet does take 4 or 5 years to reach flowering size, but no matter. To quote an old Chinese saying: ‘The longest journey begins with the first step.’”

My little hyacinth bulblets are now in their second season of growth. I’ll keep them growing strongly until their leaves yellow as they go naturally dormant, probably late this spring. Come fall, I’ll dig them all out, separate them, and then plant them out in a nursery bed or else in their permanent homes. I expect aromatic bliss in a couple of years.

And, On Another Note

I was recently a guest on Susan Poizner’s radio show/podcast where we talked about growing uncommon fruits, here at my farmden and in general. Hear it at https://orchardpeople.com/growing-uncommon-fruits/