HEAVEN AND(?) SOME HELL

/10 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening, Pests/by Lee ReichThe Blueberry Capital

A few turns after Exit 38 on New Jersey’s Garden State Parkway and I, a blueberry nut, soon entered what a visit to Bristol, Virginia would be to a country music nut, what Tupelo, Mississippi would be to an Elvis Presley nut, what Springfield, Massachusetts would be to a basketball nut, what . . . A big, blue sign declares Hammonton, New Jersey the self-proclaimed “Blueberry Capital of the World.” Literally millions of pounds of blueberries are picked and then shipped from this region of New Jersey each summer.

A few more miles and a few more twist and turns through the New Jersey Pine Barrens brings you to Whitesbog, New Jersey, “the birthplace of the domesticated, highbush blueberry.”

Let’s parse that last accolade.

“Domesticated:” Blueberries are a native American fruit that up until the early part of the last century were harvested only from the wild. No one cultivated them! Then Elizabeth White, a cranberry grower in Whitesbog, teamed up with Dr. F. V. Coville of the USDA to study and improve the blueberry. Ms. White instructed her pickers to search out the best wild blueberry bushes, which were moved to her farm. Dr. Coville investigated the rather specific soils (such as those of the Pine Barrens) enjoyed by blueberries (such as those of the Pine Barrens), and further evaluated and bred Ms. White’s selections. And the rest is, as they say, history.

“Highbush:” A number of blueberry species exist but the large berries for fresh eating that you see on market shelves are highbush blueberries, botanically Vaccinium corymbosum. Canned blueberries are usually another species, lowbush, botanically V. angustifolium. Dr. Coville and subsequent breeders have mated these two species as well as a number of other species with the goal of producing the elusive perfect blueberry. (Elusive to blueberry breeders, not to me; I like just about all of them.)

New Blues

After passing field after field of cultivated blueberries alternating with dense woodland, I turned into the parking area of the Marucci Center for Blueberry and Cranberry Research & Extension to meet with USDA research geneticist Dr. Mark Ehlenfeldt.

We looked at the fields of sandy soils formed into caterpillar-like, mulched mounds atop which were planted the bushes. We talked about the various species — V. constablaei, V. darrowii, V. ashei, in addition to the previously mentioned highbush and lowbush — that parented the various bushes.

Best of all, we plucked fruit to taste from many different varieties, some of which I grow and others of which are new to me. A few new ones that really stood out for me were:

•Sweetheart, for its medium-size that ripen early with excellent flavor

Sweetheart blueberry

•Cara’s Choice, also with excellent flavor, in addition to pinkish flowers; ripening mid-season

•Razz, a soft berry with a hint of raspberry flavor, and

•ARS 00-26, a small blueberry with a sweet, wild blueberry flavor.

Another blueberry variety that was very interesting, and perhaps tasty, was Nocturne, whose fruits, as they ripen, go from pink to bright red to blue black, making them very ornamental.

Pink Champagne

Nocturne blueberry

Nocturne fruits are supposed to have a unique flavor, sweet and somewhere between that of highbush and rabbiteye (V. ashei); they weren’t yet ripe so I wasn’t able to taste them. I did get a plant last year that is now ripening fruits so I can soon vouch, or not, for their flavor.

Two hours and many blueberries eaten later, I was on my way home.

Note: Not all the varieties mentioned are currently commercially available.

Beatlemania — I Hope Not

On a negative note, I saw here today (June 29th) the first Japanese beetles of the season, three on some grape leaves and four on some black raspberry fruits. I could just throw up my hands and brace myself for the few weeks of attack. Spraying pesticides is not an option; the beetles feed on hundreds of species. I’d have to spray just about everything here, including fruits ready to harvest, which is a no-no.

I’m hoping the beetles take the same tack they have for the past two years, a few showing up, and then, shortly thereafter, doing about faces and leaving for the season. I have no idea why.

Worst case scenario is that they descend in hordes, in which case I’ll remind myself that plants can tolerate a certain amount of damage, with remaining leaf area working harder to compensate for leaf area chewed away. Also, the beetles make their exit in August.

I pulled the seven beetles I saw off their respective plants, threw them on the ground, and stomped on them. Not out of anger or meanness, though. Beetle feeding attracts more beetles. I didn’t want any invitations for their friends and relatives.

GOOD SUMMER BLUES

/1 Comment/in Flowers, Pests/by Lee ReichPlan Realized

Almost two years after my plan was conceived . . . success. Looking across rows of tomatoes, corn, onions, and kale in my vegetable garden, I see tall, blue spires of delphiniums that have finally come of age.

The spires required some effort. Coarse roots of the seedlings called for an extra dose of care. Potting soil could easily fall from the roots, exposing them to drying air, as the seedlings were successfully moved to larger quarters.

And then, once seedlings were planted out just beyond the western fence of the vegetable garden, my chickens threatened them. The poultry enjoy scratching for insects near the bases of plants. Doing so weakens larger plants, even woody shrubs; doing so can kill tender young seedlings. Chicken wire laid on top of the ground let the delphinium plants grow up through the 1 inch openings while preventing chickens’ scratching.

Planning for Future Blues

The delphinium show will end any day now, especially with this hot weather. It’s hard to let go of the show — and I don’t necessarily have to. Sometimes a second, later show can be coaxed from the plants. If the stalks with spent blossoms are cut back to the bottom whorl of leaves, new flower stalks will spring forth that should bloom again later this season.

Good growing conditions help bring on this second show. That means rich soil and water, as needed. These I have provided for my delphiniums in the form of compost topped with a leafy mulch, and drip irrigation. “Good growing conditions” also means cool growing temperatures, which I cannot provide.

Even under the best of conditions, delphiniums, although perennials, are short-lived perennials. Before next spring I’ ll get some fresh seed — freshness of seed is important for good germination — and start a bevy of new plants. For the freshest seed possible, I’ll collect them from my own plants by gathering whole stalks when they are partly dry and then shaking out seeds. Planted immediately and kept slightly cool, they should sprout in a few weeks and flower next June. Sometimes they even self-sow.

Doing What Good Gardeners Do

Self-sown delphinium seedings are most welcome; not so for many other self-sowers, that is, weeds. Now is the time when many summer weeds pick up steam. Now is also the time when good gardeners and mediocre gardeners take different paths.

I want to be a good gardener so I’m planning, immediately after I dot the last word of this report, to go out and weed. My garden is generally not very weedy, mostly because I never — yes, never — till or otherwise turn over the soil. And because I snuff out small weeds with an annual mulch of compost in planting beds and wood chips in paths. (Mulching and never tilling also bring many other benefits, such as encouraging more vibrant soil life, better use of water, and, well, not having to till.)

Purslane

Still, weeds have made inroads. I can’t help but remind myself that every weed that goes to seed could self-sow to spawn myriad more of the same — for example over 50,000 seeds per pigweed plant, or almost 20,000 seeds per dandelion plant! Perennial weeds, unchecked, build up energy reserves in their roots and spread by traveling roots, as well as by self-sowing. Checking growth of these weeds now makes for a bountiful fall garden and much fewer weeds next year.

Mostly, I just bend over and pull out weeds, coaxing them out, if need be, with my hori-hori knife. Where weeds are too numerous to make one-on-one treatment too tedious, I slide my winged weeder or wire hoe along the ground to dislodge them all at once. I gather up most pulled and hoed weeds and cart them over the the compost. Sweet revenge: light-, nutrient-, and water-stealing weeds recycled into garden goodness.

Amongst the weedy interlopers are some worth separating out, for eating. Among my favorites are pigweed, which makes an excellent cooked green. And purslane, very healthful and tasty if doctored up correctly, good suggestions for which can be found in Foraging & Feasting: A Field Guide and Wild Food Cookbook by Dina Falconi and Wendy Hollender.

EDEN’S GARDENS

/0 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening, Soil/by Lee ReichEden’s Start with Good Soil

G, as I’ll refer to him, has a blank canvas, about 10 acres of mostly open field. His vision is, essentially, for a Garden of Eden, with fruit trees, bushes, and vines, vegetables, nut trees, and flowers. Before he even thought about digging his first planting hole, I suggested he learn something about the soil beneath his blank canvas.

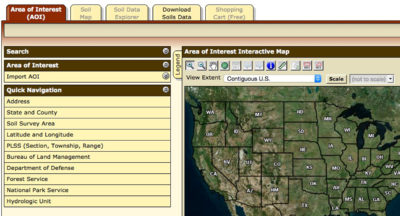

Your and my tax dollars have contributed to a most useful soil resource for G (and you and me), the Soil Web Survey, put out by the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) of the USDA. This survey provides soils maps of more than 95% of the counties in the U.S., each map delineating what lurks beneath the surface.

Web Soil Survey, opening page

Soils are distinctive, as different from one another as robins are from blue jays. These differences are harder to appreciate, of course, because soil is mostly underground, hidden from view. But if you were to dig some holes a few feet deep and then look carefully at their inside surfaces, you would find that soils are made up of layers of varying thicknesses — called horizons. And one soil might differ from the next not only in the thicknesses of its various horizons, but also in just how the various horizons look and feel. There might be horizons as white as chalk, as red as rust, or as dark brown as chocolate. A horizon might be cement hard, gritty with sand, or stuff for sculpture. And if you were to tease the dirt along one edge of the hole so it falls away naturally — wow! — each horizon would reveal its particles clumped together in such arrangements as plates, blocks, or prisms. Such information, and more, has allowed soils to be classified, much as birds, flowers, and living things are.

Armed with this information, G can know what will thrive in his future paradise and what might need to be done to better accommodate what he wants to grow.

Tax Dollars at Work

The Web Soil Survey is an easy-to-use online resource. Either google it or go directly to http://websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov/App/HomePage.htm. The big green button labelled “START WSS” gets you started.

The first step is to define your “Area of Interest (AOI)”, that is, your own back forty. Reading down from the AOI tab, you come to the “Address” line, in which, after clicking, you can fill in your own street address. Hit “Return” and, to the right, you’re zoomed into an aerial photo centered on the specified address. Click on one of the two boxes labelled “AOI” (which one depends on whether your AOI is going to be a rectangle or a random polygon) just above the map to delineate, in red, your AOI. Double click the last point and the map enlarges around the defined area.

Area of Interest defined

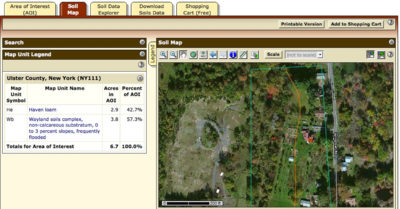

Back to the tabs at the top of the screen, and click on “Soil Map.” Now you know what to call your soil. Yes, its name. If more that one soil exists within the AOI, squiggly lines will delineate their names and extent.

From there, all sorts of useful and not so useful (for you) information are at your fingertips. Click on the soil name and you get a slew of information on that soil, including the all-important drainage class, depth to a restrictive layer, depth to water table, and its ability to hold onto water. Other clicks get you to the soil’s potential use for recreation, construction materials, building site, even military operations.

Most important is soil depth and drainage. G’s is fine, facilitating his first step towards Eden.

A Tree of Eden

Speaking of Gardens of Eden reminds me of fruit and western Asia. Which brings us to a mulberry now ripening in a pot sitting on my front terrace. This mulberry is quite different from those trees now ripening their fruit practically every few hundred feet around here.

Pakistan mulberry fruit

For one thing, this mulberry comes from western Asia, Islamabad, Pakistan, so is not cold-hardy here in New York’s Hudson Valley. Hence the pot, in which the plant resides during winter in my basement, along with figs, pomegranates, and other subtropicals.

The hardy mulberry trees that pop up here and there throughout most cold regions of the U.S. include Asian white mulberries (Morus alba) and out native red mulberries (M. rubra), and their natural hybrids. Note that fruit color has nothing to do with the species. White mulberry is a very variable species, in hardiness, fruit color and flavor, even leaf shape.

Pakistan mulberry is also unique for the size of the berries. Each is a couple of inches long. In warmer climates, the berry can elongate to over 3 inches.

Pakistan mulberry tree in pot

I wouldn’t trouble myself with a potted fruit tree just because it’s exotic and large-fruited; the flavor makes the effort worthwhile. They have a heavenly flavor, among the most delicious of all mulberries, on a par with the world’s best fruits: a rich berry flavor fronting a congenial background of sweetness offset with just the right amount of tartness.

Pakistan is sometimes listed as a variety of white mulberry, other times as a variety of yet another mulberry species, M. macroura. Outdoors, it can grow to 60 feet. In my Garden of Eden, the potted tree will be restrained to 5 or 6 feet.