Gardening by the Book

/6 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichAn outdoor temperature of 8.2 degrees Fahrenheit this morning highlighted what a great time winter is for NOT gardening, but for reading about gardening. A lot of gardening books, new and old, end up on my bookshelves, and I’d like to note a few favorites new to my shelves last year.

(Disclaimer: I had a new book published last year, The Ever Curious Gardener — available here. I like the book very much.)

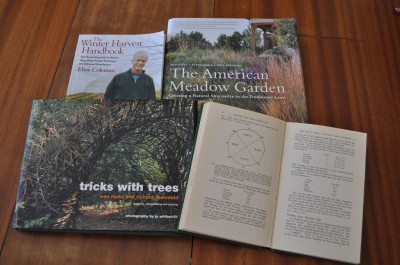

For anyone serious about vegetable growing, Eliot Coleman, gardener extraordinaire, is the author to seek out. The Winter Harvest Handbook builds on his The New Organic Grower (recently re-issued to celebrate its 30th year since publication!) and Four Season Harvest, delving into innovative techniques for growing vegetables more efficiently and year ‘round, with minimum heat inputs even in northern climates.

The “aha” moment for me in reading Eliot’s method’s for year ‘round harvests was that sunlight, even this far north, is not limiting plant growth in winter. New York City and Madrid are at the same latitude! Mediterranean gardeners don’t abandon their vegetable gardens in winter; they just change plants, growing vegetables, such as spinach, lettuce, cabbage, and radish, that tolerate and enjoy cold weather. What we need on this – the cold side – of the big pond are ways to contain the earth’s heat and/or to provide heat efficiently to keep plants alive and growing. Read the book.

The title of the book Tricks with Trees, by Ivan Hicks and Richard Rosenfeld, doesn’t do justice to the neat things shown that people have done, and you could do, with trees. How about a tree trained as a chair, a living chair? Don’t expect to move such a chair anywhere because it’s rooted in the ground. One of my other favorites in the book is the “cloud seat.” (Use your imagination and you might guess what this is.)

People love the idea of meadows, perhaps because meadows seem low maintenance, perhaps because humans originated in the savannahs of Africa. Meadows have become very popular over the last few decades, and lots has been written about them. (I even have a meadow section in my book Weedless Gardening.) The American Meadow Garden, by John Greenlee, offers all you need to know and to grow a meadow. Saxon Holt’s photographs were so inspiring I contemplated turning my one-acre meadow into, well, more of a meadow. After seeing the photograph on page 41, I want shooting stars, a milkweed relative, in my meadow, which gets nothing much more than a yearly mowing.

Greenlee’s book does keep you grounded with plenty of information about the plants, about preparing the ground, and about maintenance, especially weed control. Maintenance? Weed control? Yes, a meadow, depending on your aspirations, may need both. My only beef with this book is that Greenlee makes no mention of mowing with a scythe, a most pleasant and very efficient tool for meadow maintenance.

Last, but certainly not least, is Science and the Glasshouse by William Lawrence. If the title sounds a bit old-fashioned, it’s because the book is old-fashioned; it was written in 1950. I visited Eliot Coleman this past summer and sometime during the visit we were lobbing titles of our favorite books back and forth. He threw me this one after I had lobbed to him Intensive Gardening, by Rosa O’Brien, also 1950 vintage and one of my favorite gardening books of all time (and one he had suggested to me back in 1973).

Back to Science and the Glasshouse, which I ordered asap, actually asaicgo (as soon as I could get online). My favorite thing about this book is that it challenges many commonly held notions by testing them scientifically. Mr. Lawrence, then head of the Garden Department of the acclaimed John Innes Horticultural Institute in Britain, subjected to scientific inquiry such beliefs as: cold soil is harmful to potted seedlings (it is not); crowding potted plants decreases growth of individual plants (sometimes); size matters, in pots for transplants (yes), and so on.

The second half of the book is devoted to the “glasshouse,” which greenhouses literally were back then. Mostly, his testing showed that plants in greenhouses did not always get all the light they should, not because of a lackadaisical old sol but because of dirty glass, poor orientation, and other things we can control. Which brings us around full circle back to Eliot Coleman’s capitalizing on winter sunlight.

Some Dirt Under the Fingernails

Okay, I am, in fact, doing a little gardening. I went down to the basement and brought 2 amaryllis plants upstairs to get them started growing for blossoms in February(?).

A Wizening Little Tree

/4 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichNow, in its tenth year, my weeping fig is just waking up. (This plant is not one of my edible figs weeping from sadness, but a species of fig — Ficus benjamina — with naturally drooping branches.) As a tropical tree, its sleep was not natural, but induced, by me.

In its native habitat in the tropics, weeping fig grows to become a very large tree that rivals, in size, our maples. The effect is all the more dramatic due to thin aerial roots that drip from the branches, eventually fusing to create a massive, striated trunk. Because the tree tolerates low humidity, it’s often grown as a houseplant. Growth is rapid but with regular pruning the plant can be restrained below ceiling height.

At ten years old, my weeping fig is about four inches tall with a trunk about 5/8 inch in diameter and no aerial roots. Four inches was about the height of the plant when I purchased it in the houseplant section of a local lumberyard. Actually, four of these plants were growing in a 4 inch square pot. I separated them and potted one up with the idea of creating a bonsai.

The bonsai has been a success. Each year the trunk and stems have thickened to create the wizened appearance of a venerable old tree, in miniature. The soil beneath the spreading (if only 3 inch) limbs is soft with moss which has crept slowly up the lower portion of the trunk.

To Sleep, My Little Tree

Even after ten years the plant is in the same pot in which I originally planted it, a 4 by 6 inch bonsai tray only about an inch deep. Biannual repotting and pruning has been necessary to keep the stems and roots to size, and to refresh the potting soil to provide nutrients and room for roots to run (albeit very little room for a tree with such size potential).

Back to my tree’s sleep: A few weeks ago, the sun dipping lower in the sky for a shorter time each day seemed to me like a good time to give the plant a rest, which it surely would be taking following my operation.

I began with the roots. After tipping the plant out of its pot, I used a fork to tease soil away from the bottom of the root ball. Roots left dangling down in mid air as I held the plant aloft were easy to trim back. I was careful to leave the top portion of the roots and soil undisturbed in order to keep the mossy blanket intact.

With enough fresh potting soil added to the pot so the tree (despite its size, I think I can call it a “tree”) would sit at the same height in the pot as previous to pruning, the tree was ready to return to its home. I firmed it in place.

Next, I turned to the above ground portions of the plant, beginning by pruning stems so the tree would look in proportion to the size of its container and to maintain the increasingly rugged look of a tree, in miniature, beyond its actual years.

Finally, I clipped each and every leaf from the plant. This shocks the plant to sleep and reduces water loss, important for a plant from which a fair share of its roots have been sheared off. Clipping off leaves also induces more diminutive growth in the next flush of leaves, so they are more in proportion to the size of the whole plant.

After a thorough watering, the tree was back in its sunny window. And there it sat, leafless, until a few days ago, when small, new leaves emerged.

Pruning Moves Outdoors, Prematurely Perhaps

Pruning and repotting the bonsai wasn’t enough gardening for me. A couple of sunny days couldn’t help but drive me outdoors. A pile of wood chip mulch delivered a few months ago beckoned me; I spread it in the paths between my vegetable beds, a pre-emptive move to smother next season’s weeds.

I don’t usually prune this time of year (The Pruning Book, by me, recommends against it!), but couldn’t restrain myself. I started with the gooseberries and currants, both of which are super cold hardy plants so are unlikely to suffer any damage from pruning now. Plus, they start growth very early in spring.

Any of this gardening could be postponed until late winter or early spring. But why wait?

Shears Galore

/8 Comments/in Pruning/by Lee Reich

For Those Smaller Cuts

What gardener doesn’t need to prune some thing at some time? In many cases, a thumbnail suffices, as when pinching out the growing tip of a marigold or basil plant to make it grow more bushy. Or pinching off the soft green tip of a young apple shoot to temporarily stall its growth and let the leader, destined (by you) to be the future trunk and main limb, to remain top dog. Your thumbnail, though, isn’t always sufficiently long to use as a pruning tool, or else stems have toughened up beyond your thumbnail’s capabilities.

When more than your thumbnail is needed, there are many pruning tools from which to choose. If you’re going to own but one pruning tool, that tool should probably be a pair of hand shears, which are useful for cutting stems up to about 1/2” across.

As with everything these days from cold cereals to corn chips to soaps, a wide, confusing array confronts you whether in a catalog, the web, or a store shelf. Having written a book about all aspects of pruning, inc

Bypass blade (left) vs anvil blade (right)

luding the tools of the trade (The Pruning Book), I’ve been afforded the opportunity to try out a slew of pruning shears. Looking for a pair to buy? I’m going to make it easier for you

Okay, okay, personal taste does come into play here. That’s why the ideal is to be able to fondle a candidate before purchase or, even better, try it out. Still, some general design features are important to function.

The blades, for instance. Blade configurations fall into one of two categories: anvil and bypass (the latter sometimes called “scissors”). The business end of the anvil-type shears consists of a sharp blade that comes down on top of an opposing blade having a flat edge. The flat edge is made of plastic or a soft metal so as not to dull the sharp edge. Bypass pruners work more like scissors, with two sharpened blades sliding past each other.

Anvil shears generally are cheaper than bypass shears — and the price difference is reflected in the resulting cut! Unless the single, sharp blade is kept truly sharp, the anvil pruner will crush part of the stem. And if the two blades do not mate perfectly, the cut will be incomplete, leaving the two pieces of the stem attached by threads of tissue. That wide, flattened blade also makes it more difficult to get the tool right up against the base of the stem you want to remove.

The blades of some bypass shears are hooked at their ends to help prevent stems from slipping free of the jaws as you cut. Other shears achieve the same effect with a rolling action of one bypass blade along the other as the handle is squeezed.Beyond blade design, certain special features found on some pruning shears might appeal to you personally. Some shears are tailored to fit left hands or small hands, although on some of the latter the effect is achieved by merely shrinking the maximum blade opening when adjusted to the smaller hand size.

To make it easier to slice through thick stems, some shears have a ratchet action; weigh the virtue of more power against the need for repeatedly squeezing the handles for each cut. Other shears (allegedly) ease hand strain by having models with hand grips that rotate as you make the cut and/or varying the angle of the blades in relation to the handles.

And My Favorite Pruning Shear Is . . .

I have a collection of pruning shears and they all hang on the wall near the back door. A good test of how I actually feel about a particular pruning shear is how frequently I grab it as I go out the door.

I have narrowed down my favorites to three, which are . . . ‘rat-a-tat-tat’ drum roll. Well, it depends on what I’m pruning. If it’s just light pruning, I generally reach for my Pica shears, a model that should be better known. They’re light but sturdy, and their blades are hooked at their ends to (I guess) help prevent stems from slipping free of the jaws as you cut.

For the heaviest cuts I’d make with a hand shears, I reach for my Felco No. 7, universally recognized as great shears by those in the know. It has a nice feel, although a little topheavy, and the blades are of high quality steel and are replaceable, as are most parts.

My favorite all-around shear, the one I’d get if I could own only one shear (shudder the thought!), is my ARS VS-8 pruner.

Not a catchy name, but a top notch pruner with good weight, good steel, replaceable parts, and — my favorite part — easily opened with just a firm squeeze of the handles.

So there they are, my recommendations. Consider these before making an impulse purchase for whatever shear happens to be staring you in the face.