A MATTER OF TASTE

/7 Comments/in Vegetables/by Lee ReichMost Important, to Me at Least

Hints of summer already are here, not outside, but in the seed catalogues in my mailbox, on seed racks in stores, and from emails from seed companies. Look how many different varieties of each vegetable are offered! Thumbing through one (paper) catalogue, for example, I see twenty-eight varieties of tomato, seventeen varieties of peas, and eleven varieties of radishes. Anyone who has gardened for at least a few years has their most and least favorite varieties of vegetables. Here’s a sampling of mine.

Right from the start, I admit that most important to me in choosing a vegetable variety is flavor. I’ll grow a low-yielding variety, even one that’s not particularly resistant to insects or diseases, if it is particularly delectable. Within reason, of course.

Let’s start with one of the most widely-grown backyard vegetables, tomatoes.

REVEALED

/0 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichOnly for Gray-Haired Ladies?

I’m coming out. Today. Let me explain.

Decades ago, when just starting getting my hands in the dirt, I — perhaps other people, perhaps it was even true — thought it was only gray-haired ladies who grew African violets. As it turns out, a number of years after I had started gardening, I was offered an African violet plant (by a gray-haired lady). Back then, before I had accumulated too many plants, I was less discriminating than I am these days. I accepted.

I figured I could provide the special conditions African violets demand, according to what I read in numerous publications. “Proper watering and soil moisture is critical to your success,” I was told by one publication. I could provide the needed consistently moist soil with a potting mix especially rich in peat, compost, or some other organic material. I could monitor the plants thirst by lifting the pot to feel its weight or by periodic probing its soil with my electronic moisture meter.  I could of course be careful to avoid leaf spotting by not spilling any water, especially cold water, on the leaves. Watering from below would do the trick, with periodic leaching from above to prevent buildup of salts. They also like high humidity.

I could of course be careful to avoid leaf spotting by not spilling any water, especially cold water, on the leaves. Watering from below would do the trick, with periodic leaching from above to prevent buildup of salts. They also like high humidity.

Other requirements of African violets that were and are stated are temperatures 70-90 degrees (F) by day and 65-70 degrees at night. I was also admonished to keep an eye out for pests, including aphids, cyclamen mites, and mealybugs, and symptoms of disease. Root rot, for example.

Oh, and regular feeding should be administered except when resting (to the plants, not me).

NEW PLANTS, UP IN THE AIR

/2 Comments/in Houseplants/by Lee ReichAsexual Propagation

One of my great enjoyments in gardening is propagating plants. So many ways to do it! You can take stem cuttings or root cuttings, or you can serpentine layer, tip layer, or stool layer. And then there’s grafting, of which, as with layering and cuttage, many, many variations exist. Whole books have been written on plant propagation, even solely on grafting. My favorites for these two topics are Hartmann and Kester’s Plant Propagation: Principles and Practices and R. J. Garner’s Grafter’s Handbook.

The above mentioned methods of propagation are asexual. New plants are made from mother tissue of an existing plant. As such, all the new plants are clones of the mother plant. Not always, though.

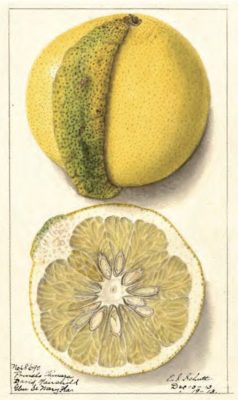

Grapefruit chimera

A plant chimera, analogous to the lion-goat-dragon of mythology, is a plant made up of two genetically different cells, a plant mosaic. Depending on what part of the plant you take for propagation, you end up with a clone of one or the other cell type, or, perhaps, both (the chimera). A plant usually broadcasts that it’s a chimera with splotches or lines of color different from the surrounding color of the leaves, flowers, or fruits. (Splotches or lines of color can also be caused by viruses.)