A FRUITFUL YEAR?

High Hopes

Apple, pear, and plum branches frothing in white blooms this spring foretold of bountiful crops of these fruits. Wrong. They foretold of the potential for bountiful crops. I’ve mentioned before the abundance of insect and disease pests that lurk here, ready for action, and the potential for late spring frosts. So I don’t get my hopes too, too high with these fruits, except for the pears, European and Asian, which are naturally pest-free here.

Lots of things can be blamed for a barren fruit tree, bringing disappointment no matter what the cause.

Apricot trees in bloom

If the tree is young and not yet of flowering age, fruitlessness can be forgiven. Pears, for all their qualities, are typically slow to come into bearing.

Who Needs a Mate?

There’s many a slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip. That plum tree bedecked in flowers is no guarantee of fruit to come.

Cross-pollination may be needed. This means that the flowers need pollen from a different variety of the same type of fruit. No fruit will be borne by an isolated McIntosh apple tree, or two McIntosh apple trees planted near each other. On the other hand, neighboring McIntosh and Golden Delicious apple trees both will produce fruit. Most apples, pears, sweet cherries, Japanese plums, and hybrid plums need cross-pollination. Peaches, apricots, tart cherries, and European plums (dark-blue, oval plums) generally do not need cross-pollination, so even isolated trees ccan bear fruit.

Peach blossoms, no mate needed

Some flowers have pollination shortcomings. Winesap, Mutsu, and Jonagold are among the few apple varieties that are triploids so their pollens are effectively sterile; they can’t pollinate any other apple varieties. Magness pear flowers don’t produce any pollen at all. In such cases, where cross-pollination is needed and one variety produces poor pollen or no pollen, three different varieties must grow near each other for all to fruit.

Some flowers are fastidious about their mates. Bartlett and Seckel pears, for instance, each produce viable pollen. But they can’t pollinate each other. Some incompatibilities also exist amongst varieties of sweet cherries and hybrid plums.

Fruit trees don’t all read and follow these rules. In California, Bartlett flowers don’t need any mate; the trees carry on all by themselves and set seedless fruits!

Pollen Here, Pollen There

The blossoming period of trees that need to cross-pollinate must overlap. Usually this is not too much of a problem, unless, for instance, one were to plant a very early blossoming apple like Lodi with a late-season blossoming one like Macoun (and there were no other apple trees nearby).

Trees need to be within about a hundred feet of each other for effective cross-pollination. If cross-pollination is needed but lacking, all that’s needed is to plant another tree or graft one branch of a different variety onto the tree. An easier and quicker solution is to beg or steal some flowering branches from another tree (remember, it must be a different variety) and put their bases in a bucket of water beneath your tree. Or get a neighbor to plant a suitable pollinator.

If a fruit tree blossoms yearly, but produces varying amounts of fruit each year, the problem could be poor honeybee activity. Pollination is effected mostly by honeybees, but they go on strike if the weather is too cold (below 50 degrees), too rainy, or too windy (more than 15 mph). Such conditions rarely prevail throughout the entire blossoming period, so fruit trees may not produce enough fruit, but at least they produce some fruit.

Many species of wild bees also pollinate fruit trees. They actually transfer more pollen per bee than honeybees. They’re also not so finicky about working in cold, windy, or wet weather. Encourage these insects by maintaining some wild areas with a diversity and abundance of nonnative and noninvasive annual flowering plants (cosmos, buckwheat, and lacy phacelia, etc.) and native plants (hyssop, purple coneflower, bee balm, prairie clovers, blazing star, goldenrods, New England aster, etc.).

A possible recourse to poor pollination would be to hand pollinate the blossoms with an artist’s brush. This is a commercial practice in intensive orchards in Japan. Also, since most insecticides are toxic to bees, it would be foolish (and illegal) to spray such chemicals on fruit trees in bloom.

Frost Problems

Variable production from year to year, with no fruit some years, also can result if the blossoms or developing fruitlets freeze. The critical temperature depends on the type of tree and the stage of bloom, but generally speaking, start to worry as the mercury drops to the high twenties. Apricots bloom early in the spring and their blossoms often succumb to late spring frosts. A sheet or a blanket thrown over a small tree might keep flowers a few critical degrees warmer than the ambient air.

Super dwarf peach tree, easy to blanket from frost

You can tell if cold has damaged developing fruitlets if you sacrifice one and slice it in half. A blackened center indicates cold damage.

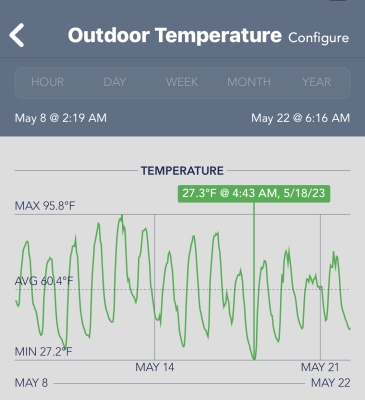

This year, here at the farmden, temperatures plummeted to 27.3° F. at 4:43 am on May 18th (information thanks to my Sensorpush sensor).

Sensorpush registering night’s temperature

Fortunately this was after fruit set, so the freezing temperatures did little damage. My sensor is near ground level and temperatures were probably a bit higher a few feet above ground, in the trees.

Not Finished Yet

Okay, so you have good pollination and the weather has been cooperative, but there still are no fruits on your tree. Animals could be the culprits. Some insects cause small, developing fruits to drop. Plum curculio (her activity is not restricted only to plums) is one such insect whose tell-tale sign is a crescent-shaped scar on the fruit.

Curculio on apple fruitlet

Curculio scar on maturing apple

As fruits enlarge, they become appealing to furry and feathered animals. I know of an apricot tree that is stripped clean of its unripe fruits around Farther’s Day every year by a squirrel hungry for the developing seeds. The evidence: ground littered with split open, green apricots.

One way to keep insects at bay

For all these potential problems, remember that fruit trees have for eons been driven by the same goal as you and me: to produce ripe fruit. In anticipation of poor pollination, adverse weather, and insect predation, these trees usually set more fruit than they have the energy to ripen. Come June, the trees seem to breathe a sigh of relief as they shed excess fruits.

Don’t let the falling fruits of “June drop” scare you. You’ve got to grit your teeth and actually twist off excess fruits, enough to leave a few inches between apples, pears, peaches, or nectarines. That channels the tree’s energy into the remaining fruits so that they grow larger and tastier. No need for this task with cherry, plum, or apricot trees.

Plums self-thinning

What are those bags around the fruit made of? Where can I get these?

They’re organza bags, with drawstrings, readily availableonline in various sizes.

Where I live – northwestern NJ – I have observed every species of bee that has been catalogued as native as well as honeybees. I can stand under my old standard apples and honey locust and listen to the constant humming of bees at work. One problem I have with pears is that crows come and strip the fruits very early, so early that those fruits are little more than rock-hard bumps on the branches.

Same here with the bees. No crow here, fortunately. You have some unusual pests there.

Would it be worth it to bag pears? is the first year in getting any fruit from them.

Last year I had lots of dimpling and stone cells from stink bugs. So this year I bagged some pears.Not all, so I’ll see if stink bugs are around and if the bags helped. I’ll report back.

in the last couple few weeks I lost nearly all the apples on my 3 mature trees and I have no idea why. I thinned by hand before they were the size of a dime. there was plenty of fruit then. there were also plenty of visible pests, so I hit them with the Surround soon after (admittedly about a month after flower fall, on the later end of the window to start, by my understanding). I guess it could have been deer, but they’ve never left this little fruit. I’m talking like 15 apples left between 3 25′ tall and wide apples… any advice? this is in Rensselaer county

It’s probably plum curculio. One spray of Surround is not effective. You have to build up a coating with 3 sprays before the plants even bloom. The spray weekly to maintain the powdery coating on the plant, or after every 1/4″ of rain. It’s a lot or spraying.

thank you! and bummer. do you use something else, other than surround?

I have used Summer many times. I have so many pests of apples and plums here that I’m going to give up on them. The spraying wiwth Surround is just too much spraying.