I GET MY KICKS

Roots Do It

Some people get their kicks from hang gliding; some from racing cars. Call me mundane, but I get a similar thrill, minus the fear, from seeing cuttings of some new varieties of figs that I am propagating take root. The cool thing about hang gliding, racing cars, and rooting cuttings is also the sense of satisfaction you get from doing it well.

The current batch of cuttings provides special satisfaction because the method I used, gleaned from the web (see, for instance, what turns up with a search for “fig pops”), permit me to check and observe progress frequently. Usually, I stick a cutting into a rooting mix and learn that rooting has taken place by the resistance of the stick to an upward tug or by roots escaping through the drainage hole in the bottom of the pot. With fig pops, I get to see each cuttings wiry, white roots wending their way through the rooting mix soon after they first start to develop. Fig pops are also a way to root lots of cuttings in a small space.

The current figs are rooting in 3” by 8” clear, thin plastic bags filled with my usual 1:1 mix of moist peat moss and perlite. I pushed the cuttings, fig “sticks” of last year’s growth 1/4 to 1/2 inch thick, into the mix almost to the bottom, then sealed the top closed with a twist-tie. One cutting per bag. Roots need to breathe, so I poked each bag full of holes with a toothpick. That’s it, except when the bags seemed too dry I stood them in a pan with a couple of inches of water for awhile.

(Dipping the cuttings in a commercially available rooting hormone would probably improve rooting, but I don’t use them. To me, the health precautions needed when dealing with them takes the fun out of gardening.)

All that, and time, would have been enough. But to speed things up, I moved the cuttings to a place where they’d get some warmth on their bottoms. That could have been atop a refrigerator, above, but not on a radiator, or, in the case of my cuttings, on a seedling heating mat.

No light is needed until cuttings start to leaf out. Which is an exciting moment, because roots might — or might not — begin to show about then. All that’s needed is to lift a fig pop and take a look. Some of mine showed roots after only 3 weeks! But it’s good to let them get well rooted before disturbing them.

No light is needed until cuttings start to leaf out. Which is an exciting moment, because roots might — or might not — begin to show about then. All that’s needed is to lift a fig pop and take a look. Some of mine showed roots after only 3 weeks! But it’s good to let them get well rooted before disturbing them.

When the time came to move a well rooted cutting, I sliced the plastic on the bottom and up along one side of its bag and put the whole root ball in a bona fide pot, filling in with bona fide potting soil around it.

That’s it. Growth will pick up with increasing warmth and sunlight. And then fruit, which could arrive on the branches even this growing season. Figs are admittedly easy to root by any method. As with any cutting, an important ingredient for success is patience.

Graft (Nonpolitical) is Good

Moving on, next week, to another perennial source of excitement here in the garden: grafting. I do this every year about now? Why every year? Because I’m always getting scions (1-year-old stems for grafting) of new varieties of fruits, mostly pears, to try out or to replace existing varieties. Or I might want another tree or two of a variety particularly worth growing here.

If I’m replacing an existing variety, I do a Henry the Eighth on the tree, lopping off its head, low, to graft a new variety onto the remaining stump. With the established root system underfoot, these grafts grow very vigorously and bear relatively quickly — sometimes the year after grafting.

Alternatively, I make a whole new tree by grafting a scion onto a one-year-old rootstock that I purchase or grow. These small trees will take longer to come into bearing, how long depending on the kind and variety of fruit, and the rootstock.

Stump of older graft

A rootstock, whether the remaining stump of a lopped back mature tree or a pencil-thick young plant, has to be closely related to the scion that will be grafted atop it for the graft to be successful. Rootstock and scion in the same genus generally do well together, so pear on pear, apple on apple, even peach on plum are compatible. Occasionally, plants in the same family but different genus, such as pear and quince, also join well.

Whip graft

One way to create a rootstock would be to just plant a seed, giving rise to the appropriately named “seedling” rootstock. A seedling rootstock’s main claims to fame might be its general toughness and its genetic diversity from other seedlings. That genetic diversity is a downside if you want to plant an orchard of uniform trees; it’s an asset if you don’t want some pest all of a sudden wiping out all your plants with genetically the same rootstocks.

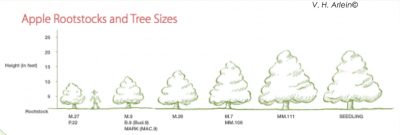

Rootstocks have been selected or bred that impart special qualities to a tree, and these rootstocks are propagated not by seed, but by any one of a number of methods of cloning (cuttings, tissue culture, mound layering, etc). Most dramatic might be the effect on plant size. The Malling 27 variety of apple rootstock, for instance results in a tree that matures at about 7 feet high. As with many dwarfing rootstocks, the tree also yields its first harvest quickly with, although less fruit per tree than a larger tree, more fruit per sure foot of space. And you can plant many dwarf trees in the same space as one full-size tree.

Dwarf trees also have the advantage that pruning, harvesting, and other needs can be met with your feet planted on terra firma. Any disadvantages? Yes: more finicky about growing conditions, much shorter lifespan, and often needing staking throughout their lives. But there are many rootstocks from which to choose, especially with apples and pears, so you can choose what suits you from a fully dwarfing tree on up to full-size tree. A rootstock might also be selected for its tolerance for certain soil conditions, hardiness, and other environmental hazards.

Most important: The rootstock, for all its effects, has little or no influence on the flavor of fruit grafted upon it.

I’ll be grafting next week. Stay tuned for the 2 or 3 easy grafts I use to make trees.

Do you think that this method would be useful for rooting cuttings that aren’t necessarily as enthusiastic rooters as figs, like pears? Also, if a pear tree has volunteers from below the graft, would rooting the rootstock and fruitstock separately and then grafting them together create an immature tree, or would the age of the parent rootstock transfer to the newly rooted rootstock (which might make for earlier fruiting)?

Yes, it should work well for all cuttings — except those that almost never root, such as pear and apple. If you did root from below the graft, age would transfer depending on how how high up on the plant then stem came from. The lowest parts of a plant always remain juvenile. Actually, age of rootstock is immaterial as far as the graft is concerned. Vigor of the rootstock is more important, which is why top grafting a tree, which has an established root system, results in such vigorous regrowth.

Those are some nice-looking figs!

How are yours doing?

Great idea on the bags. Do you have a source for them?

Uline sells them but for the small quantity I wanted at a good price I went to http://www.clearbags.com

For plants that root easily, say, currants or gooseberries, is the primary advantage of rooting in a peat/perlite mix the speed at which roots develop (due to heat)?

I have been sticking cuttings directly in the soil in the fall in the location where I want the new plant. My thought was that less root disturbance is preferable, but perhaps that advantage is more than off-set by the amount of roots a cutting will produce if exposed to higher temperatures.

I suppose the questions of interest are whether one approach yields more fruit or fruit sooner or a healthier plant that yields more fruit over it’s life-span (all else being equal).

Not all gooseberries, in my experience, root easily. The advantage of the peat/perlite mix is that it provides good aeration and water holding. It does not provide heat; my heating mat did that.

I don’t think either method would affect yield or overall health differently.

I think I asked you this before, will this work for elderberries?

Yes.

Have you ever tried the clear ventilated orchid pots in which baby orchids are grown?

Good article. I’m going Togo try this on pussywillow cuttings I took yesterday!

Pussywillow cuttings root VERY easily. They’ll root under almost any conditions, almost if you just drop a stem on the ground.

So when you say it should work for all cuttings, are you just referring to fruits? What about native honeysuckle, weigela, azaleas, etc?

All plants that root from cuttings, yes. But many plants do not root readily from cuttings.

Good stuff, always something to learn.

Do you use mycorrhizae in your cutting mix? In the past you’ve mentioned that you use garden soil as an inoculant in other situations, do you use it here?

Gardeners are always moaning about their poor soil, but I’ve got it really bad. I’m in central California, 8 miles from the coast, on real adobe clay. In our no-rain summers the soil turns brick hard. There are no worms in this soil. Naturally, I’m always on the lookout for ways to improve the soil. I use lots of compost, both homemade and purchased mushroom compost by the yard. Do I need to add mycorrhizae to my arsenal? Is it worth the thirty some bucks to get some of this magic dust to add to whatever I plant or propagate?

Thanks for all the good information.

Generally, take care of the soil, which mostly means using plenty of organic matter and minimizing disturbance, and mycorrhizae will be there. Add mycorrhizae without good soil conditions, and they won’t thrive. When I was in graduate school, one of my experiments involved assessing the role of mycorrhiza on blueberries. I had trouble keeping the control plants, which were not inoculated, from getting naturally infected.

Inoculants for legumes are a whole ‘nother ball game. Even then, all that’s needed is a one-time inoculation with an appropriate organisms. Different legumes require different bacteria.

I’m trying for figs and apples in my patio garden this year. Will I have any issues growing an apple on semi-dwarf rootstock (rather than fully dwarf) in a container? I’m hoping to espalier it. Thanks Lee

The dwarf espalier apples should work fine, especially if the variety is a “spur type”, which set fruit at a younger age and more readily than non-spur types. The dwarfing rootstock also helps wit this.

This is new way to root figs or any root stock. I have 100 brown turkey fig cuttings in sand right now. I trimmed a old tree for a friend last year & the new growth suckers went wild this year & I pruned them for him. Some looked like coach whips, had a arm load, so I rooted some of them.

I have heard of burying cutting 24 inches deep in winter & digging them up in spring.

I have heard of rooting them in water, i have done this. But your bag method or Bens is knew to me. I hope to root about 10 varieties for the farm.

Thanks for the new method.

Great article, thanks, Lee. Can I use the same method on a Hydrangea? thanks!

Yes!

Propagating paw paws from the root suckers: can it be done? I’ve failed twice now; is it the wrong time?

Problem is that suckers are connected to the mother plant so usually, or for some time, do not have roots of their own to provide adequate support. I have, though, heard of successful transplanting of the suckers. Perhaps dig around it with a shovel one year, then transplant the next year.

This time (before I got your reply) I chose one further away from the mother plant, put it in as big a pot as I could, and put it under the grow lights with an inverted bell jar (thanks to your suggestion in The Ever-curious Gardener) and the leaves haven’t wilted yet. We’ll see! I plan on moving within the next year, so I can’t take a multi-year approach, unfortunately.

This is great information and I appreciate the detailed photos! may I ask what season/timing you used for taking the cuttings? It says the diameter and mentions previous year’s growth, but did you cut them in fall winter or early spring?

Anytime the plants are leafless and dormant is okay. I prefer fall, but then have to make sure I am able to keep them cool and moist so the buds don’t start expanding. There’s more chance of that happening with cuttings taken in early spring. Of course, winter is also a time for taking cuttings.

Thank you.