GOOD FUNGI, BAD WEEDS

Myco . . . What?

There’s a fungus among us. Actually, fungi, all over the place. Right now, though, I’m focussed on a special group of fungi, a group that, as I look out the window on my garden, the meadow, and the forest, has infected almost every plant I see. Like so many microorganisms — most, in fact — these fungi are beneficial.

The fungi are called mycorrhizal fungi; they have a symbiotic relationship with plants. (“Mycorrhizae” comes from the Greek “myco,” meaning fungus, and “rhiza,” meaning root.) The plant and the fungus have an agreement: The plant offers the fungus carbohydrates which it makes from sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water; in exchange, the fungus infects plant roots and then spreads the other ends of its thread-like hyphae throughout the soil to act to be virtual extensions of the roots. The plant ends up garnering more mineral nutrients from the soil. The fungus also helps offer protection against pests and drought. It’s an arrangement that has worked for eons.

Except for where soil has been doused with heavy doses of pesticides or discombobulated by land excavation, mycorrhizae are everywhere. Only a few plant families get along without this symbiosis. Some more familiar, nonmycorrhizal plants include cabbage and its kin, carnations, lamb’s-quarters, and sedums. Other plants can grow without mycorrhizae, but then miss out on some of the benefits and don’t make most efficient use of minerals soil has to offer.

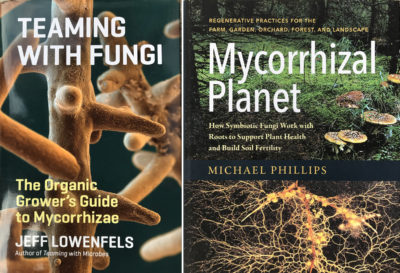

Why mention mycorrhiza at this moment of time? Two books on mycorrhiza were published this year; either one, but not both, are worth reading. Both cover the kinds of mycorrhizae, their effects, their nurturing, and probably everything else you might want to know about this symbiosis.

Michael Phillips’ Mycorrhizal Planet will appeal more to the hip gardener, the one who burns wood for biochar for their soil, builds hugelkultur mounds (look it up), and spritzes plants with herbal extracts to boost their immune function. He’s mostly right when writing about mycorrhizae but often enters the land of woo-woo when venturing off-track. For instance, he writes, and then runs with, “many species of insects lack the digestive enzymes needed to break down complete proteins.” Not true.

The other book about mycorrhizae, Jeff Lowenfels’ Teaming with Fungi, presents a similar overview to mycorrhizal fungi, and their application, to that presented in Mycorrhizal Planet, with one notable difference. Teaming with Fungi details straightforward methods how you or I can actually grow our own mycorrhizae with which to inoculate plants to get them off to the best possible start.

The two books differ dramatically in their writing style. I eventually tired of Phillips’ overly flowery style and anthropomorphizing. “The synergy that unfolds as a result of outrageous diversity in the orchard delights me to no end . . . .The root systems of fast-growing tree with relatively pliable wood make barter possible between AM [arbuscular mycorrhize] and EM [ectomycorrhizae] fungi.” Lowenfels’ Teaming with Fungi is more firmly grounded in real science and application than Mycorrhizal Planet. I found Lowenfels’ writing more straightforward and engaging: “Some trees form AM, but others have evolved over time and are hosts to EM. Some trees are hosts to both forms of mycorrhizae, though usually at different periods in their lives.” (Different strokes for different folks.)

The mycorrhizal symbiosis was first studied and described in the latter half of the 19th century. Less long ago, but still long ago, I studied them as part of my doctoral work, specifically the ericoid mycorrhizae that are specific to blueberry plants and their kin. With the increased appreciation of the diversity, extent, and effect of the living world within the soil in recent years, mycorrhizae have moved into the spotlight. Read about them, nurture them, and make use of them.

And Weeds Among Us

Rising now to see what’s going on aboveground, I see that the garden has moved mostly into its maintenance phase for the season. That entails mowing, scything, making compost, keeping an eye out for pests and taking action, if necessary.

And, of course, weeding. My weeding weapons of choice are my hands, for larger interlopers, and either the winged weeder hoe or wire hoe for small ones. Called into action weekly, either of the two hoes easily slice through the top quarter inch of soil surface to do in small weeds that haven’t even yet poked their heads above ground.  All the better to forestall the appearance of large weeds, which are much harder to kill and also threaten to spread seeds or grow strong roots. Regular hoeing also keeps the soil surface loose to better absorb rainfall.

All the better to forestall the appearance of large weeds, which are much harder to kill and also threaten to spread seeds or grow strong roots. Regular hoeing also keeps the soil surface loose to better absorb rainfall.

Early July seems to be when true gardeners part ways with other gardeners. Regular weeding and other garden maintenance keeps the garden in good shape for the fall garden which, with good maintenance and planning, is like having a whole other garden, providing vegetables and flowers well into fall.

I appreciate your commentary and I enjoy your books. I will say, I appreciate the “woo woo” of Michael Phelps, as much as the scientific nature of other resources. That said, I need more woo woo in my life because as a nurse, I have too much science on a daily basis!!! I also employ M.P.’s natural methods for my small orchard in the Adirondacks and have had much success to this point (5 years). So I say, “bring on Mike O’Riza!!”

Michael Phelps ???? Okay Diane, just kidding. I’ve been collecting and using mycorrhizae for over 30 years. My experience is different from most readers here, including this blog’s owner as it appears you are somewhere up north and east. Presently I live in Sweden for the past 11 years, but I come from the desert and mountain areas out west in Southern California. So certain species specific fungi to those areas were of most concern to me. I’ve never been into most of those permaculture Hugelkultur mounds, etc which make me think of some type of tribal ritual for psycological benefits. Whatever. Out west I do innoculate everything when planting new into an urban setting. Also in the wild when I lived in the mountains above Palm Springs and had a lot of acreage. I never bought into the claim, “inoculation is not necessary because the spores are just everywhere in the air.” Yes, ectomycorrhizal fungal spores could be in many places in the air after their truffles or mushrooms dry out and explode spew spores into the air, but endomycorrhizal fungi have underground propagules which do not operate the same way as those air born ectomycorrhizal spores. They are a larger spore and don’t move as well within the soil spores. Another thing I discovered is that when I planted Coulter and Jeffrey Pines on my property in between chaparral shrubs like scrub oaks, these shrubs also became colonized with the Pisolithus tinctorius I inoculted on the outplanted seedlings and immediately the following year were also producing truffles or puffballs near closely to their driplines and the health and vigor of the foliage had also dramatically changed. Oddly enough in some of the wild stands of pines these PT Mycorrhizal Fungal puffballs were present in the area, but not in all locations. So the air wasn’t good enough a source. From the late 1990s until I left there in 2006, the vegetation (pines and oaks) were declining. One of the things I noticed was the lack of any truffles when I went collecting until finally there were none and eventually even the older pines trees died. I always wondered if there was a connection between the fungal puffball disappearence and eventualdeath of the trees. So in many areas (even in the wild) you may well have to inoculate and not depend on the air. The other practice I did was over a period of decades, I learned which chaparral shrubs works best with interconnecting with tree seedlings and faciliated their growth through the conections. Most Chaparral is endomycorrhizal, but they have extremely deep root systems which work wonderfully with hydraulic lift and redistribution of subsoil moisture and the PT mycorrhizae will tap into that moisture. There’s more, but I don’t have the time.

I’m also a hands on weeder, but if I design the urban landscape setting just right with natives and like non-natives with similar requirements and have built up a healthy mycorrhizal soil system, this has always favoured shrubs & trees and weeds are not able to compete for any phosphorus as the mycorrhizal fung outcompetes the weeds. My mother has a third of an acre in *el Cajon California and the remaining time I spent there (2001 to 2006) I turned her yard around and the only weeds now that pop up are shrub and tree seedlings. Ruderals for the most part now are absent.

Paul Stamets writings are good and informative, but when he says “Fungus can save the world or reverse climate change”, I have to disagree. Only people can do that through the correct choices based on education of how nature works.

Lee, do you know if fungal innoculants for blueberries are commercial available? From what I’ve read they need fairly specific EM fungi and I’m not sure if they can be sourced.

I would not worry about mycorrhizae on your blueberries. That was one of the topics I researched for my doctorate. It turns out that it was very hard to keep my blueberries from becoming mycorrhizal, even in initially sterile media. The only reports of non-mycorrhizal blueberries that I remember were from Australia, where they are not native. One thing you could do is just take some soil from established blueberries somewhere and dig it under your plants or throw it in the planting hole.

https://pureagproducts.com/products/pureblue?variant=38781723012&country=US¤cy=USD&utm_medium=product_sync&utm_source=google&utm_content=sag_organic&utm_campaign=sag_organic&srsltid=AfmBOopt8cxNevUMqhfGLIaHPNiJwY0-51E9PCaz7J2SPe_fX2bP8LLcGd0

I am a blueberry grower, and while I have purchased this product for a new planting, I have yet to use it. But this is seriously the ONLY product that I have found to focus specifically on ericoid mycorrihizal fungi.

Yes, blueberry and its kin do have a special, ericoid mycorrhizal association. I worked with hose fungi as part of my doctoral work, and found that these fungi were pretty much ubiquitous. Even plants in sterile soil that was not inoculated developed mycorrhizal. That would not be the case in parts of the world where blueberries are not native. Australia, for instance.