GOOD GERMS

Despite its sinister sound, a “germplasm collection” spells good things for farmers and gardeners alike. Think beyond the flu season and the word germ takes on a broader meaning: a small mass of living substance that can give rise to a whole organism or one of its parts. Think of wheat germ, that nutritious part of a wheat seed that contains the cells — the germ — that develop into a whole new wheat plant.

My Collection Swells

To us gardeners, a germplasm collection is a collection of plants or seeds. Forty years ago, I started amassing a collection of gooseberry varieties, A collection that swelled to almost fifty of them! Besides offering good eating, that group of plants was at the time one of the largest germplasm collections of gooseberries in the country.

Some of my gooseberry varieties

No, the fruits didn’t all taste good, but I was reluctant to part with any variety that I was not sure would also be available elsewhere. After all, some desirable gene — for disease resistance or pretty color for instance — might be hidden within a variety that didn’t taste good to me. Or someone else might like a variety’s flavor even if I didn’t.

Gooseberries, by the way, are not all small, green, and tart. In my collection I had varieties that would swell to the size of small plums (the appropriately named variety Jumbo, for instance), some in various shades of red, and some smooth-skinned and some hairy (Winham’s Industry, for example).

Gooseberry variety Jumbo

And most of my plants bore “dessert” fruit, that is, in the words of Edward Bunyard (The Anatomy of Dessert) “the fruit par excellence for ambulant consumption.” Some steered towards apricot flavor, some towards plum, some would explode in your mouth when you bit down to release their sweet, ambrosial juice.

My Collection Shrinks

In 1970, southern leaf blight disease swept through Midwest corn fields, reducing the crop by 700 million bushels. Disease spread was possible because of the heavy dependence, at that time, of all the country’s corn on just a few genes. That blight helped prompt the formation of the U. S. National Plant Germplasm System, a national system for acquiring, maintaining, characterizing, and distributing germplasm of crop plants.

My corn planting

Our National Clonal Germplasm Repositories, one part of the System, are home to clones. Here, plants such as McIntosh apple, Hass avocado, and Thompson Seedless grape, none of which can be propagated from seeds, are maintained as living plants. Mulching, pruning, and keeping the labelling in order on fifty gooseberry bushes was a big job for me. I can hardly imagine what it would take to similarly care for the two-thousand five-hundred plus varieties of apples at the apple repository in Geneva, New York.

A basket of heirloom apples

Over two dozen other germplasm repositories are scattered across the country. Each houses plants well-adapted to the region. You’ll find the papaya collection in Hawaii, the avocado collection in Florida, the blackberry collection in Oregon, the asparagus collection in Iowa, and so on for scores of other ornamental and crop species that must be maintained as living plants.

The National Seed Storage Laboratory and four Regional Plant Introduction Stations are another part of our Germplasm System. At these sites, alfalfa, barley, rice, wheat, and other plant varieties that can be grown from seed are preserved as such in cold, dry rooms conducive to long term storage.

You think your boxes of seeds are overflowing? The National Seed Storage Laboratory at Fort Collins, Colorado keeps seeds of a half a million types of plants in good condition.

Altogether, our germplasm system plays nursemaid to about a half a million varieties of plants. This germplasm might be used by plant breeders and other researchers to develop new varieties. Curators can also lend help to researchers, as well as to you and me, in obtaining obscure varieties not offered by nurseries. All holdings are entered into GRIN, the Germplasm Resources Information Network, a computerized database which also can be accessed online at www.ars-grin.gov.

I was happy to donate my gooseberry collection, in the form of cuttings and/or whole plants (I can’t remember which) to the USDA’s growing collection some thirty plus years ago.

Plants for the Future and from the Past

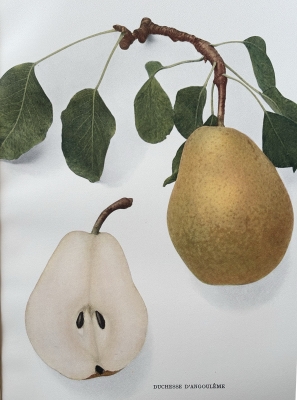

Duchesse d’Angoulême pear, from THE PEARS OF NY, 1921, U.P. Hedrick

A few years ago, I was looking for a pear named Duchesse d’Angoulême, a variety that dates back to 1812 and is known for its large size and delectable, buttery flesh. The Germplasm Repository at Corvallis, Oregon counts this variety among the thousand plus pears in its collection, and I was sent some stems for grafting.

Unfortunately, that variety did not do well here on the farmden. No matter; I did a Henry the Eighth on the tree and grafted a different variety on the resultant stump.

The National Plant Germplasm System is a two way street, and thousands new varieties are added to collections each year. The Corvallis repository is now home to 176 gooseberry varieties. After donating plants to the Corvallis facility, my collection was pared down to about 20 varieties. I’m paring again, down to the half dozen that do well here and meet my gustatory standards: Poorman, Hinonmakis Yellow, Black Satin, Captivator, and Chief.

Because diseases can hitchhike into this country on imported plants, quarantine centers also make up part of our National Plant Germplasm System. At these sites, plants are tested, observed, and, if needed, quarantined before being allowed elsewhere in the country.

In 1979, I imported some musk strawberry (Fragaria moschata) plants that had to be quarantined because of virus infection; it was two more years before the plants finally made it to my garden. (I happened to be doing my doctoral research at a USDA Belstville Research Center, conveniently located near the USDA Glendale Plant Introduction Center.)

The wait was worth it: that strawberry’s flavor is a most delectable melding of strawberry, pineapple, and raspberry.

Musk strawberry fruit

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!