IS REAL SOIL GOING TO POT?

What’s in Your Mix?

That potting soil that you’ve bought for your seedlings and houseplants? It probably has no REAL soil at all in it. Real soil is just too hard to obtain in reliable and uniform quantities for commercial packaging. Soilless mixes, as commercial potting soils are (or should be) called, are a mix of some kind(s) of organic materials along with some aggregate, with possible additions of fertilizer, ground limestone, and a wetting agent.

Organic materials in these mixes help sponge up water and cling to nutrients that might otherwise wash down and out of the pot. Peat moss is the organic material traditionally used in soilless mixes. Although it holds water well, it’s initially hard to wet, which is why wetting agents are sometimes added to soilless mixes.  Sawdust, shredded bark, coir (shredded coconut husks, a byproduct of coconut processing), and Pitmoss (made from shredded newspaper) are other organic materials sometimes used in soilless mixes.

Sawdust, shredded bark, coir (shredded coconut husks, a byproduct of coconut processing), and Pitmoss (made from shredded newspaper) are other organic materials sometimes used in soilless mixes.

Aggregate is added to soilless mixes to help keep water moving down and out of a pot to leave some air spaces for good aeration. The most commonly used aggregates are vermiculite, a kind of clay heated so that its layers expand like an accordion, and perlite, a volcanic rock “popped” at high temperatures. Vermiculite eventually breaks down in a potting mix, which makes perlite a better choice for aerating mixes for plants that are only infrequently repotted, such as large house plants.

Other materials used as aggregate include sand and calcined montmorillonite clay (sometimes the ingredient of kitty litter). Like organic materials, vermiculite and montmorillonite, but not sand and perlite, cling to plant nutrients so they don’t get away before roots get to them.

Coarser bark or wood pieces could also function as aggregate — until they decompose, in which case they would function more like organic materials, which they are. Another possible aggregate-like material is rice hulls. For years a large bag of rice hulls has been leaning against my workbench. I’m hoping to try them out in a potting soil someday but am not sure whether their function would be aggregate or organic material.

Soilless mixes have advantages beyond their uniformity. They are lightweight, a consideration with large, potted plants. And they are sterile or easily sterilized, so help avoid problems with soil-borne diseases and weed seeds.

Potential Problems

Still, problems can arise using soilless mixes. Without the buffering power of real soil, more careful attention is needed to soil pH and correct feeding of plants. And feed you must, because the organic materials and aggregates used in soilless mixes generally have little nutrient value. Fertilizers pre-mixed into commercial potting mixes are soon exhausted.

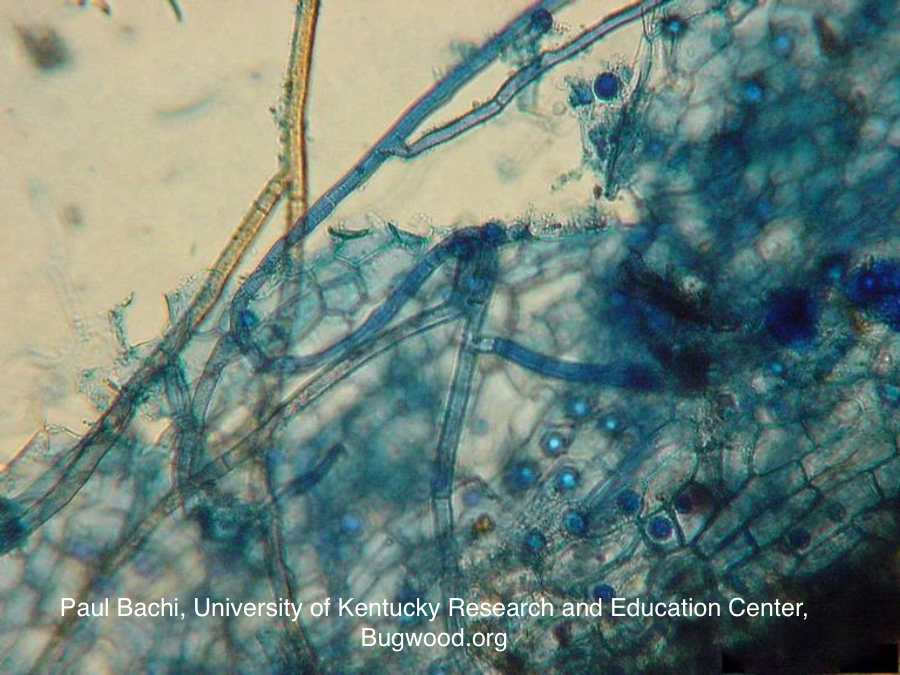

Also, soilless mixes are not immune to soil-borne diseases. Diseases can arrive from spores wafted through the air, from dirty tools or fingers, or from seeds, cuttings, or plants already carrying diseases. Once diseases get a foothold, they can run amok without having to battle any of the beneficial microorganisms present in real soil.

Damping off disease of cabbage seedling

Soilless mixes also have an environmental downside. Peat is only slowly renewable, and intense heat is needed to make the vermiculite, perlite, or montmorillonite clay for potting mixes.

Despite their drawbacks, soilless mixes do have their place in gardening. They are most useful for starting seeds that germinate very slowly and for rooftop or balcony gardens, where weight is a consideration.

You could get more mileage and other benefits from a commercial soilless mix by adding to it a half part of real soil and/or compost. For a bespoke mix for cactii and succulents, which need especially well drained soil, add 1/4 to 1/2 by volume of sand or perlite to a commercial mix. The sand adds weight to the pot to help keep some of these top heavy plants from keeling over.

Orchid plant, with equal parts wood chips added to mix

For cuttings I sift together equal parts peat and perlite. Cuttings don’t need nutrients until they’ve rooted and start growing in earnest.

African violet leaf cuttings

My Recipe

I like to make my own potting soil for the same reason I like to make bread or compost. The results in both cases are better than most commercial products. And less expensive.

I also use my mix for seedlings

Making up a batch of potting soil is the usual overture to my gardening season, and in this case I do mean potting “soil.” I start with a batch of real soil, either stockpiled or dug up from my garden and sifted through 1/2-inch mesh hardware cloth. In order to kill weed seeds, I moisten the soil, if dry, and microwave it to bring its temperature up to about 180° throughout. Once cooled, I spread it out on the workshop floor or in my garden cart,

I start with a batch of real soil, either stockpiled or dug up from my garden and sifted through 1/2-inch mesh hardware cloth. In order to kill weed seeds, I moisten the soil, if dry, and microwave it to bring its temperature up to about 180° throughout. Once cooled, I spread it out on the workshop floor or in my garden cart, then pile on equal parts compost, peat moss, and perlite, topped with, per 10 gallons of mix, about a cup of soybean meal for an enduring source of extra nitrogen.

then pile on equal parts compost, peat moss, and perlite, topped with, per 10 gallons of mix, about a cup of soybean meal for an enduring source of extra nitrogen.

Before anyone raises their hand to ask, “What about weed seeds in the compost?” . . . my compost piles usually usually reach 150°F, which is high enough to kill off weed seeds. Also, microwaving compost could overheat it, which causes bad things to happen, such as release of too much manganese, a micronutrient that, in excess, is toxic to plants.

If I was going to make a more environmentally friendly potting soil I would start by trying various substitutes for peat moss; I’ve done that, but so so far they’ve proved unsatisfactory. I incorporated them as if they were peat moss. By right, they should be tested in varying proportions. I would also use coarse sand instead of perlite. Some day.

Call me provincial; for now I’m sticking with the same mix I’ve been making up for each growing season for decades. “I have seen gardens which were all experiment, given over to every new thing, and which produced little or nothing to the owners, except the pleasure of expectation” (C. W. Warner, My Summer in a Garden, 1871). I’m still recovering from last year’s failed potting soil “experiment.”

Hi Lee,

In researching repotting my bonsai, I was dismayed to see that the most frequently suggested combos is equal parts pumice stone, lava rock, & akadama. Pebbles! So I add 1 part compost to it, maybe some garden soil too.

But now I wonder if I’m spreading the Asian Jumping worms if I give stuff away in it…

I just learned what akadama is. If you’re worried about worms in akadama, to me that seems unlikely since it generally is heat treated. For my one bonsai plant, a weeping fig now about 13 years old, I use my regular potting mix along with a little extra perlite. It has worked well, sustaining the plant with twice a year root, shoot, and leaf pruning, and repotting. The plant’s home is a shallow pot less than an inch deep and less than 4 x 6 inches.

I’m trying to envision microwaving garden soil. Do you do it in batches? How much do you microwave at a time?

Yes, in batches of about a gallon each for about 20 minutes. You can just check the soil temperature in the middle. 180 degrees shout do it.