PLOTTING ALONG

Possible Sources of Anxiety

Especially in years past, I would get a little tense this time of year, because sometime soon I would have to sit down and map out the year’s vegetable garden. As usual, ideas have been bouncing around inside my head for the past few weeks, but the day must come — before April 1st, my date for planting peas — when procrastination must bow to action.

When that time comes, I gather together on the kitchen table printouts of the empty beds in my two vegetable gardens, a sharpened pencil, and notes and plans of gardens past. After taking a deep breath, my first order of business, planning for crop rotation, begins. The theory: Plant no vegetable in the same spot sooner than every third year. The rationale: A garden pest might survive the winter to bother the same plant the following year . . . unless the plant happens to be growing elsewhere, in which case the pest starves and dies.

Pests usually are equally fond of all plants in a plant family, so I won’t grow tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, or potatoes (nightshade family) at the same location without waiting three years. Ditto for cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, or Brussels sprouts (brassica family), beans or peas (legume family), and carrots, celery, celeriac, or parsley (umbellifer family). Of course, in the years before I replant tomatoes, I might grow carrots, then beans, then cabbages in that bed.

Too a lesser extent, I also rotate plants according to their nutrient uptake from the soil. Leafy vegetables (spinach, lettuce, cabbage) take a lot of nitrogen from the soil, beans and peas add nitrogen to the soil, fruiting vegetables (tomato, pepper, eggplant) soak up phosphorus, and root vegetables (carrots, radishes, turnips) use a disproportionate amount of potassium.

Endive bed, with lettuce

In the bed right near the garden gate, I might grow a leafy vegetable one year, then a fruiting vegetable, then a root vegetable, then a pea or bean, and finally back to the leafy. I follow the same rotation in the adjacent bed, beginning perhaps with a fruiting vegetable. And so on around the garden.

So much for theory. In practice, I’m always tucking lettuce, radishes, onions, sometimes even cabbages, in among other plants helter-skelter throughout the garden. And how can I resist using the fence around my gardens to support peas, squashes, melons, and cucumbers?! (The latter three are in the same family.) There just aren’t enough fences with garden beds at their feet to support a rigid rotational scheme.

I find some consolation for my sloppiness knowing that crop rotation is to no avail when dealing with a pest such as striped cucumber beetle, which has no trouble flying thirty feet across the garden from where last year’s cucumbers were to where this year’s cucumbers are. Also, as Eliot Coleman told me decades ago when I was a novice gardener, just because an insect can attack a plant doesn’t mean it will. (I was going to follow recommendations to avoid planting strawberries in lawn newly converted to garden because of root-gobbling grubs often found in lawns. I followed Eliot’s advice, planted strawberries, and enjoyed a nice crop of berries.) I am diligent, though, about rotating tomatoes to avoid leaf-spotting diseases, which can defoliate plants by summer’s end.

More Anxiety

Because I always try to eke the most from every square foot of garden space, I incorporate another scheme — succession cropping — into my garden planning. The theory: Few vegetables are in the garden from the time the soil first thaws in spring until the first frost in autumn, so a given spot in the garden could have more than one crop back to back during the same year.

Leek, lettuce, mustard, radish

Looking over my notes, I see that in previous years I have successfully cropped lettuce, arugula, radishes or other short season, cool temperature vegetables before and/or following tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, edamame, even sweet corn, and other warm season vegetables. Those short season, cool temperature vegetables can even precede long season, cool temperature vegetables such as broccoli and cabbage, the seedlings of which I don’t transplant into the garden until mid-July.

Cabbage, lettuce interplant

My final cropping scheme — again to maximize use of space — is intercropping. The theory: Until large plants fill out their leafy canopy, there’s room between them for smaller plants.

Endive, escarole, & broccoli

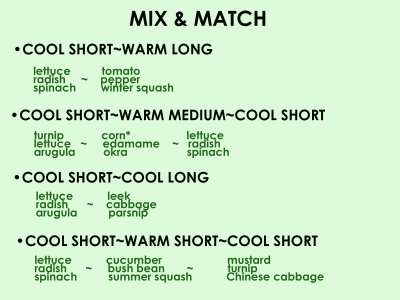

I stick onion sets, which I harvest as scallions, between early lettuces, between cabbages, and around tomatoes. Lettuce goes between pole beans, tomatoes, or broccoli, and a few radish seeds here and there in a carrot row are up and out of the way by the time the carrots build up steam. I’ve grown broccoli plants in a bed with a solid green ground cover of elbow to elbow curly endives. (See “Mix & Match” chart for more.)

Calmness Reigns

Are you beginning to see why my nerves used to get edgy when it is time to plan the garden? They used to get especially edgy as I tried to also factor in companion planting. This wrinkle on intercropping is based on the theory that just because any two plants can physically be accommodated in a given space doesn’t mean they’ll enjoy each other’s company. Some plants are allegedly finicky about their neighbors, which might affect their growth or pest resistance. Carrots and onions, corn and squash, and tomatoes and cabbages are examples of alleged. beneficial associations.

Years ago, it was at this point in garden planning that I was ready to throw up my hands. How was I to incorporate all these cropping schemes into a harmonious, productive garden? Wasn’t gardening supposed to be a relaxing hobby? A pastoral diversion?

Over the years, my planning has become increasingly calm. I’ve accumulated a pile of previous seasons’ notes to guide me. I ignore companion planting, the bulk of which has been debunked, except for the allopathic (inhibitory) effects of certain plants on others. Also, planting in beds has allowed me to more easily move plants around the garden each year by just moving last years bed forward to the next bed.

In the early 19th century, Charles Lamb wrote “Nothing puzzles me more than time and space; and yet nothing troubles me less.” They trouble me more.

Still, when it comes to gardening, I find it most important to abide by this principle: Never delay planting for lack of a plan.

What are your thoughts on planting flowering sweet peas in the bed I last planted eating peas? I have 2 beds with an arch between them—would you consider just reversing the plantings year after year? Also (try as I might) volunteer tomatoes come up in every bed I’ve ever had them in and I just can’t bring myself to pull them out! Last but not least, I get around the potato issue by planting them in large pots with freshened up, amended soil with lots of extra compost. I do stress a bit, but I also figure I will lose some of my crops to the crop gods, LOL!

Go ahead and plant with all the peas. As I learned years ago, just because a plant might get a disease doesn’t mean it will. Rotation does lessen the possibility, but . . .

It’s always a work in progress, especially since we keep adding nee bed and plants.

I like to have an outside and then fill it in this time of year as I think about it

To me, it is art. Which of course has its angst but the rewards are worth it.

I love reading your blog and enjoying the beautiful photos of your gardens and trees! Blessings for a plentiful (and weed free) bounty this year.

“Plotting along” is a phrase often used to describe steady progress or advancement, especially in the context of a project or endeavor. It implies a methodical and consistent approach to achieving goals, where each step forward contributes to overall progress. Whether it’s gardening, work, or personal development, embracing the idea of “plotting along” can help maintain momentum and ultimately lead to success. So, keep plotting along, step by step, towards your desired destination.