ORANGES IN NY’S HUDSON VALLEY, OUTDOORS

Frightening, Beautiful, Edible

Right now, my hardy orange tree might look at its finest, standing at the head of my driveway against a pure white, snowy backdrop. An orange tree!? Outdoors with a snowy backdrop?! Okay, in all honesty, it’s a bush, not a tree. But it is an orange plant, and it does survive into Zone 5 outdoors. (Temperatures plummeted to 2° F a week ago, and coldest temperatures typically arrive around the end of this month.)

Botanically, the plant was Poncirus trifoliata. I write “was” because a few years ago, this citrus relative was welcomed closer into the citrus fold, with a new official name, Citrus trifoliata. Not all botanists recognize this closer kinship, and insist on keeping the plant in the Poncirus genus.

The kinship of hardy orange with other citrus is obvious from its glossy, forest green leaves, the sweet (but very slight) aroma of its flowers, and its fruits, which are pale orange.  The fruits are edible but I wouldn’t bite into one; the flavor is orangish, but also sour and bitter. Perhaps I’d squeeze the pulp to add a hint of citrus flavor to some other cooked fruit or a baked good. Perhaps not.

The fruits are edible but I wouldn’t bite into one; the flavor is orangish, but also sour and bitter. Perhaps I’d squeeze the pulp to add a hint of citrus flavor to some other cooked fruit or a baked good. Perhaps not.

What I like best about this plant are its stems, which are most evident now, when bared in winter. The younger stems have that same forest green color as the leaves. And the variety I’m growing, appropriately named Flying Dragon, presents a winter show that is at the same time intimidating, interesting, and decorative. The stems twist and contort every which way, and then adding to the show are numerous large, recurving thorns. All hardy oranges are thorny, but none as boldly as hardy orange.

Mix and Match

Hardy orange has proved useful to commercial citrus. Its primary use has been as a cold hardy rootstock on which to graft other citrus varieties. The rootstock results in a smaller plant that is also resistant to two serious pest problems, tristeza virus and root rot (caused by Phytophthora parasitica).

Hardy orange has also been hybridized with other citrus species in an effort to produce new, edible citrus that could endure colder growing conditions. Catastrophic cold temperatures in Florida in 1894 were an early impetus for breeding hardier citrus, and the first of these was Rusk citrange, the offspring of Ruby sweet orange and hardy orange. A 1905 publication from the USDA described the fruit as “intermediate in qualities between the two parents.” Among the uses for these new hybrids, the authors write that “citrangeade has been tested by a large number of people, and all who have made a comparison pronounce it fully equal to lemonade or limeade, while some think it superior.”

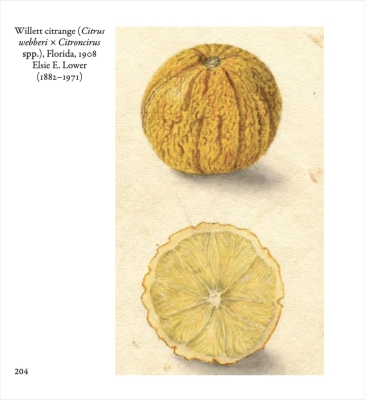

(Another of the early hybrids, Willits Citrange, is pictured in my most recent book, Fruit: From the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection. For this book, I selected 250 of the 7500 watercolors — truly beautiful watercolors — of fruit varieties commissioned by the USDA between 1887 and 1942 to show and write about.)

I’ve tasted hardy orange straight up, but not any of the many hybrids.

Poncirus, cut fruit

Despite the statement from the 1905 USDA publication and other older sources writing favorably about the flavor of the hybrids, I’m skeptical. That skepticism is confirmed by looking through various internet sites. Most writers with personal experience growing and tasting various hybrids rate it as poor: “you are not really being poisoned – it just tastes that way;” “would make you gag.” ‘Nuff said.

On the positive side, I think the hybrids do have cool names. In addition to citranges, there are citrangequats (citrange X kumquat), citrangedin (citrange X calamondin), citrumelo (poncirus X grapefruit), and citrangelo (poncirus, mandarin, & grapefruit)

Same as Mother

The coolest thing about hardy orange — and many other citrus — is apomixis. The seeds within fruits of apomictic plants can be derived from mother tissue only. That is, rather than reflecting the jumble of chromosomes resulting from male pollen mingling with female eggs, apomictic seeds are clones of the mother plant. So if you took seeds from a Mineola tangelo and planted them, the resulting plants could yield a tree that bore Mineola tangelos. Do that with a seed from a MacIntosh apple, which is never apomictic, and the resulting tree would bear a random fruit, in all likelihood not nearly as good tasting as the MacIntosh fruit from which the seed was extracted.

Not all the seeds in a single citrus fruit are necessarily apomictic and, hence, capable of growing plants that are clones of the mother plant.

Enter Flying Dragon. Many times I’ve taken seeds from a Flying Dragon fruit and planted them. In this case, you don’t have to wait for the plant to grow old to find out which ones will be clones of Flying Dragon. They’re the ones with the swirling stems, and the stems begin to do so when even about a foot high. It’s fun to grow them, but I won’t be eating any of the fruits.

Agree 100%. Here in Atlanta, they’re easy enough to grow and can create a fierce hedge in time. Fruits, although terrible to the taste, are decorative enough and hang a good time past leaf drop.

Having grown the hardy orange Poncirus trifoliata as I knew it then, the hardiness for zone 5 is overrated. As a in ground plant it died back by at least half every year. Tried wrapping it but that wasn’t much an improvement and getting the covering off too soon caused more issues from late March cold sweeps. It never flowered or fruited for me while in the ground, even after seven years. It was then potted up and bloomed the next year, setting many fruits. The flavor was strong but really not much more so than a sour orange like Seville. I used the fruits for a marmalade in which they proved to be very well suited and of good flavor. After bringing that very heavy pot indoors and under lights for a few years, it was finally discarded since it was too heavy to safely handle. Summary: The plant is too iffy a hardiness for southeast Wisconsin but will grow well in a pot provided one has an easy spot where to move it during the colder months. I had also grown seeds and gave away 75 plants to relatives, friends, and attendees at the Wisconsin Permaculture Convergence about ten years ago. My younger son still has one potted and kept indoors.

I have read that fruits of different plants do vary somewhat in flavor. Sounds like you got a good one. I did get some dieback when I was in zone 5, but now the USDA and recent years have put me and the same garden in zone 6, the plant survives much better.

Neat to learn about this! I don’t think I’ll grow it..not enough land for a fierce plant with untasty (if decorative and interesting) fruit…but I wonder too Better tasting fruit resulting from a particular soil condition? Minerals, biology…?

Nope. The fruit tastes pretty bad and it’s all in the genetics. Minerals and biology only go so far.

I met a person who used the peel to make glacé orange peels. Personally I do not consider the results to be worth the effort as a Valencia or even a Navel orange will work better, but I send this out as a possibility for those who wish to attempt it. I have had halved calamondins that had been candied and perhaps the Trifoliate Orange fruits could be used the same way – but all those seeds!

I’mm not that hungry. 🙂

Calamondin oranges don’t taste particularly good, but are delicious as compared to Poncirus.

Orange ya glad they have a peel? tee hee.

🙂