SOMETHING A LITTLE DIFFERENT, IN FRUIT

(Adapted from my book Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden, now out of print but very soon available as online version. Stay tuned. Information is also available in my books Grow Fruit Naturally and Landscaping with Fruit, available from my website and the usual sources.)

I always know when my hardy kiwifruits are ripe because my dogs and ducks start grubbing around beneath the vines for drops. The fruits, for those unfamiliar with them, are similar to the fuzzy kiwifruits (Actinidia deliciosa) of our markets, only much better for a number of reasons.

Obviously, from the name, hardiness is one reason. Hardy kiwifruits will laugh off cold below even minus twenty-five degrees Fahrenheit, while market kiwis are injured below zero degrees Fahrenheit.

Another difference is in the fruit itself. Hardy kiwifruits are grape-size, with smooth, edible skins. Pop them into you mouth just as with grapes. Within the skin, hardy kiwifruits look just like market kiwis, in miniature. The flavor of hardy kiwifruits, though, is far superior to that of the fuzzies, sweeter and with more aroma.

Okay, I have to qualify that last statement because there are actually two different species of fuzzy kiwifruits. A. chinensis, rarely seen for sale outside China, is relatively large (though usually not as large as A. deliciosa) with skin covered by only a peach-like fuzz. The flesh color ranges from green to yellow, on some plants even red, in the center. The flavor is very sweet and aromatic, smooth and somewhat tropical, reminiscent of muskmelon, tangerine, or strawberry. In all honesty, this kiwifruit has the best flavor of all — but it’s even less cold hardy than the more common fuzzy, market kiwifruit. If winter temperatures here were mild enough for me to grow A. chinensis, I would.

Two Species, One Flavor

Hardy kiwifruits also come in two species: A. kolomikta and A. arguta. But not two flavors; they taste pretty much the same.

Both are ornamental vines, so much so that they were originally introduced into this country from Asia over 100 years ago strictly for their beauty, their innocuous fruits overlooked. How many visitors pass beneath the many handsome vines planted early in the twentieth century on public and private estates, unaware of the delectable fruits also hidden beneath the foliage?

For most kiwifruits, male and female flowers are borne on separate plants. Only the females bear fruit, but males are needed for pollen to get that fruit to form. (Just like humans and most animals, the “fruit” in animals being the ovary responding to fertilization.) One male (kiwi plant) can sire up to about eight females.

The two species of hardy kiwifruits do have their differences. The one that’s ripe for me now is A. kolomikta, which I choose to call the super-hardy kiwifruit because it’s cold-hardy to below minus forty degrees F. (For a pleasant dance of your tongue, sound out and speak the species name slowly.) Kolomikta is the more strikingly ornamental of the two because of the pink and silvery variegation of its leaves.  This species is also relatively sedate in growth, so is easier to manage. One problem with this fruit, which my ducks and dogs consider a plus, is that it drops when it is ripe, perhaps because it’s ripening so quickly during hot days of summer.

This species is also relatively sedate in growth, so is easier to manage. One problem with this fruit, which my ducks and dogs consider a plus, is that it drops when it is ripe, perhaps because it’s ripening so quickly during hot days of summer.

The other species, A. arguta, is more sedately ornamental, with apple-green leaves attached to the vines on reddish leaf stalks. Fruits of this species, depending on the variety, start ripening in the middle of September, and they stay firmly attached. One problem with A. arguta, mostly for casual growers, is that it’s much less sedate in growth. My vines send out a number of 10 foot long canes every year.

Must You Prune?

Pruning keeps either species productive and within bounds. Containing the plant is especially important with A. arguta. A number of years ago, I gifted two plants to a friend. He planted them at the base of a sturdy arbor that was attached to his front door. I’m not sure he ever pruned the plant, and 15 years later the arbor was on the ground.

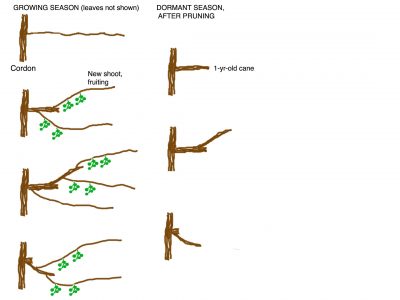

Still, either species grows best trained to some sort of structure. Mine, which are grown mostly for fruit, are trained on a series of T-shaped posts fifteen feet apart and joined at their cross-members by five equally spaced wires. Each plant’s strongest shoot has been trained to become a trunk that reaches the center wire, then bifurcates into two permanent arms, called cordons, running in opposite directions along the center wire.

Each plant’s strongest shoot has been trained to become a trunk that reaches the center wire, then bifurcates into two permanent arms, called cordons, running in opposite directions along the center wire.

Fruiting canes grow off perpendicularly to the center wire and drape over the outside wires. Flowers and, hence, fruits are borne only toward the bases of shoots of the current season that grow from the previous year’s canes, very similarly to grape vines.

Annual winter pruning entails, first, pruning off any new shoots forming anywhere along or at the base of the trunk, and shortening cordons once they have reached full length. Fruiting arms give rise to laterals that fruit at their bases; during each dormant season, cut these laterals back to about eighteen inches in length. Remaining buds on the laterals will grow into shoots that fruit at their bases the following summer. The winter after they have fruited, these shoots correspondingly should be shortened to about eighteen inches, but leave only one of these. When a fruiting arm with its lateral, sublateral, and subsublateral shoots is two or three years old, it’s cut away to make room for a new fruiting arm.

With all this said, the vines do fruit with no more pruning than a yearly, undisciplined whacking away aimed at keeping them in bounds. Such was the objective in pruning those hardy kiwifruits planted as ornamentals on old estates. These vines happily and haphazardly clothe pergolas with their small, green fruits hanging—not always easily accessible or in prodigious quantity—beneath the leaves.

Note to plant nativists: I am aware that Actinidia species are considered to be non-native invasives in many areas. I’ve grown and watched this plant for decades and have never found it growing anywhere but where I planted it. As far as I can tell, the only way this plant can spread would be for it to be planted near enough to tree stands to give the vine leg up and then to be totally neglected. I have never seen a self-sown seedling pop up anywhere.

I also have a single Kiwi Actinidia vine in my garden. One year it was particularly prolific. I remember it well as my overindulgence resulted in some gastro-intenstinal discomfort due to the Actinidain enzyme in the fruits. So yes to Kiwi’s in the farmden, but beware!

No pollinator? Generally, this means no fruit.

It was labeled as self-fertile when I bought (many years ago) but I don’t recall a cultivar name. Perhaps it is the cultivar ‘Issai’ – described by Missouri Botanical Garden as “a hermaphroditic cultivar (perfect flowers) that needs no separate male pollinator for fruit production. It is a restrained version of the species, typically growing to only 12-20′.” I can attest to both characteristics.

It seems like you have Issai.

Here in Newton NC I planted four young A. deliciosa plants in 1982 and two survived. More than a dozen years later the prolific pair of plants bore a few fruits on the fertile female. A couple of years later it produced a barrel of fruit and in recent times (except for lean fruiting following late frosts some years) it has given us a couple of barrels a year. We had constructed a sturdy 30 ft.by 10 ft. arbor which the monstrous female has overwhelmed.

It was not trained and seldom pruned even crudely. We also planted three A. arguta on a Wooden pergola (equally vigorous fecund, and undisciplined ) about 25 years ago. We are restoring the pergola We want to train the old plants to grow for fruiting. The A. deliciosa we want to convert to T trellis and wires. The proper pruning and forming of these thick multi-stem masses is daunting. What strategy would you recommend? I have recently bought your Uncommon Fruits book and Pruning Book.

Be bold. Easiest would be to cut a whole plant to the ground, then select a vigorous new shoot that grows to become the trunk and train and prune as for a new plant. With that large root system, a very fast growing “new” plant. All this would delay cropping. Selective pruning to achieve the same goal would take longer to get the plants properly trained, but you’d continue to get annual harvests.

Lee

Thanks for your response.

I am excited to have discovered your Blog!

I had shorn all the stems smaller than about one inch earlier this fall. I am prepared to take even bolder interventions.

I read that: “A. deliciosa may suffer cold injury in some years in

the Pacific Northwest. Cold damage usually occurs when temperatures

drop during the night after a warm spell, particularly when

vines are not fully dormant (in fall or late winter). The trunk usually is damaged,

which weakens older plants and sometimes kills young vines. Although methods such as wraps and plastic sleeves may help protect the trunk against freeze injury, they are not always effective. The trunk’s sensitivity to cold decreases

with age.”

Thus I am wondering when is the optimal time to coppice the main trunk of the deliciosa and the arguatas?

Also the male deliciosa is in a massive mound near the female. Does it warrant coppicing, pruning or other treatment? Would training a male cane onto the nearby new T trellis be advised?

Additionally some loops of branches of the deliciosa lying on the ground seem to have rooted. Would trying to separated these tenuously rooted stems from the main plant as propogants be practical? I wonder how to best proceed with this delicateprocess? Your wisdom is appreciated. Thanks

Deloy

I would do it after growth begin in spring when chance of late frosts are passed. The new growth will be very frost sensitive. Yes, I think it would be better to train the male also, not necessarily as rigorously as the females but enough to keep them manageable. Yes, rooted stems could be transplanted. Cut them away from the mother plant and dig them with attached roots. Depending on how well rooted they are, transplant to their final site or to a temporary nursery bed for more intensive monitoring and care.

Lee

Again thanks for your wisdom and encouragement to this always too hesitant pruner. As time for coppicing and training the almost 40 year old A. deliciosa approaches I am noticing some trunk damage at ground level. I would like to send you a photo of the plant. I wonder when I cut it to the ground whether to cut off all the main branches at their origin a few inches above ground level or even lower at the dirt which would cut through the damaged trunk. I want to “be bold” and prudent it my pruning

Thanks

Deloy

A few inches above ground level would be good.

Hey Lee – big fan of yours. Thanks for all of the wonderful tips and tricks over the years. I’m working at a farm that planted some hardy kiwifruit 5+ years ago and haven’t done much pruning at all. Is it alright to prune this time of year? Just mowed under the vines and hoping to take advantage of the access. Thanks!

Now is generally not a good time to prune anything. With that said, kiwis do go wild, even self-shading themselves, in which case removing a few stems would be beneficial. I also sometimes shear back long vines draping beyond the side of my T-trellis, making it easier to mow closer to the plants.

Got it! Will do a light prune of things down at the base and will wait for next spring to do a heavy prune. Thanks Lee!