Uh Oh, Watch Out for This One!

Past pests

Watch out for this one!

Over many years of gardening at the same location, I’ve seen pests come and go. And if they didn’t actually leave, they at least didn’t live up to the most feared expectations.A few years ago, for instance, late blight disease ravaged tomato plants up and down the east coast. The disease overwinters in the South and normally hitchhikes up north if temperatures are cool, humidity is high, and winds blow in just the right direction. That year it got a free ride here on plants sold in “big box” stores. I no longer consider late blight any more of a problem than it was before that high alert summer.

A few years ago, I was ready to say goodbye to my lily plants when I first heard of and then saw red lily beetles crawling and eating their way across my lilies’ leaves.  They’ve been making headway across the Northeast since arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1992. But my lilies still look fine and, yes, I do still see some of those beetles. Perhaps one of the natural predators released in Rhode Island years ago has joined the crowd here, minimizing damage.

They’ve been making headway across the Northeast since arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1992. But my lilies still look fine and, yes, I do still see some of those beetles. Perhaps one of the natural predators released in Rhode Island years ago has joined the crowd here, minimizing damage.

Japanese beetles were never a problem here until around 2006. I tried handpicking and trapping but their numbers — and damage — continued on the upswing.  Then, about 10 years later, and since then, they’ve showed up on schedule, which is now, but then disappeared for the rest of the season. Did they go off to greener pastures? Did they succumb to soil nematodes or fungi?

Then, about 10 years later, and since then, they’ve showed up on schedule, which is now, but then disappeared for the rest of the season. Did they go off to greener pastures? Did they succumb to soil nematodes or fungi?

And the spotted swing drosophila, which really went over the line by attacking my favorite fruit, blueberries.  Although chemical, mechanical, and biological controls are still under development, this pest has not put an end to my blueberry-eating days. Thanks to some bait and kill traps developed by Cornell’s Peter Jentsch, damage has been kept to a minimum.

Although chemical, mechanical, and biological controls are still under development, this pest has not put an end to my blueberry-eating days. Thanks to some bait and kill traps developed by Cornell’s Peter Jentsch, damage has been kept to a minimum.

The list goes on: marmorated stinkbug, leek moth, emerald ash borer, hemlock woolly adelgid . . .

Most Frightening of All!?

A new, most frightening pest is now lurking offstage. The spotted lanterfly (Lycorma deliculata, and heretofore to be abbreviated SLF) is an invasive leafhopper native to China, India, and Vietnam. It feeds on just about everything, including various hardwoods as well as grapes and fruit trees. To make matters worse, it also exudes a sticky honeydew which falls on any nearby surface (other leaves, lawn furniture, etc.) and, worse yet, becomes food for a fungus than turns that stickiness dark.

To make matters worse, it also exudes a sticky honeydew which falls on any nearby surface (other leaves, lawn furniture, etc.) and, worse yet, becomes food for a fungus than turns that stickiness dark.

This voracious pest can spread quickly; within 3 years of finding its a way into South Korea, it had spread throughout the country, about the size of Pennsylvania. And now SLF has arrived in Pennsylvania (well, actually, a few yers ago)!

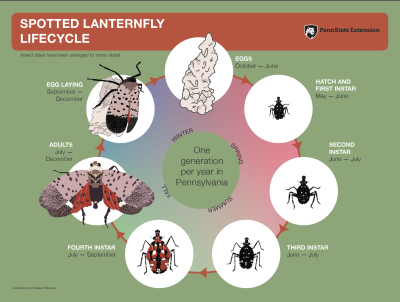

In autumn, the lanternfly lays its eggs, which get a mud-like covering, on any hard surface, be it the bark of a tree, a rock, even a car bumper.  In spring, nymphs hatch and climb trees in search of soft, new growth. The one-inch long adults emerge around now; they’re very mobile, usually jumping but also capable of flying, which is when their spread wings display their bright red color. With wings folded, the insects are mostly gray wings with dark spots.

In spring, nymphs hatch and climb trees in search of soft, new growth. The one-inch long adults emerge around now; they’re very mobile, usually jumping but also capable of flying, which is when their spread wings display their bright red color. With wings folded, the insects are mostly gray wings with dark spots. A few natural predators, such as spiders and praying mantises, feast on SLF, but not enough. What to do? There are a few approaches.

A few natural predators, such as spiders and praying mantises, feast on SLF, but not enough. What to do? There are a few approaches.

A favorite host is tree-of-heaven, a weed tree that is not a favorite of most humans. Getting rid of these trees, then, is one way to limit spread of SLF. Problem is that a single female tree might produce 300,000 seeds per year; and the trees are hard to kill, resprouting and growing quickly from root sprouts.

Systemic pesticides injected into the trees would kill any insects feeding on them. Someone recounted to me of seeing a six-inch depth of dead SLF beneath infested, pesticide treated trees!

One thing you and I can do when leaving any area known to harbor SLF is to check what we’re taking with us, on the car bumper, for instance. Currently, certain southeastern counties of Pennsylvania are under quarantine, which means that movement of certain articles (such as brush, debris, or yard waste, landscaping or construction waste, logs, stumps, firewood, nursery stock, outdoor recreational vehicles, tractors, tile, and stone) is restricted out of these areas. Although established populations have not been reported elsewhere, individual insects have also been sited in nearby states.

Keep an eye out for eggs or adults on your property. If egg masses are found, scrape them off wherever they’re attached. Because authorities are trying to monitor spread of SLF, report any siting of eggs or adults, along with photographs and location (888-4BADFLY or spottedlanternfly@dec.ny.gov, for instance).

Insecticidal soap and Neem are two organic insecticides that are effective against SLF. Both are contact insecticides so will not kill insects that arrive after spraying.

By keeping an eye out for SLF and helping to limit its spread, we can keep this pest in check at least until some natural control can step in for the job.